Woodpecker Skull Biomechanics: Natural History Illustration

Sometimes I get asked to complete natural history illustrations on topics that are as fascinating as they are random.

Last week, Bloomsbury Publishers got in touch to ask me to do a diagram for one of the books in their “Spotlight” series of natural history titles, this book will be all about woodpeckers. (I’ve done diagrams for other titles in the series including “Spotlight: Robin” and “Spotlight: Bumblebee”).

The woodpecker hyoid

This specific illustration was to be showing how a structure called a hyoid helps support the woodpecker tongue. It also has a vital role in cushioning the skull as the woodpecker is busy smashing its beak into solid wood. As stated in the article on Plos one by Wang, Cheung et al, “The woodpecker does not experience any head injury at the high speed of 6–7 m/s with a deceleration of 1000 g when it drums a tree trunk” (Why do Woodpeckers resist Head Impact Injury: A Biomechanical investigation Plos one, October 2011) This is properly extraordinary; such force would not only give most vertebarates concussion and a massive headache, but would almost certainly result in permanent brain injury too.

Green woodpecker about to smash his beak against a tree…with no ill effects

So how do they do it? As summarised by Samantha Hauserman in “Why Don’t Woodpeckers get Headaches?” there are a variety of adaptations that help the birds handle these massive and repeated impacts.

Illustration of the hyoid

The first is the structure I’ve been asked to illustrate, the hyoid.

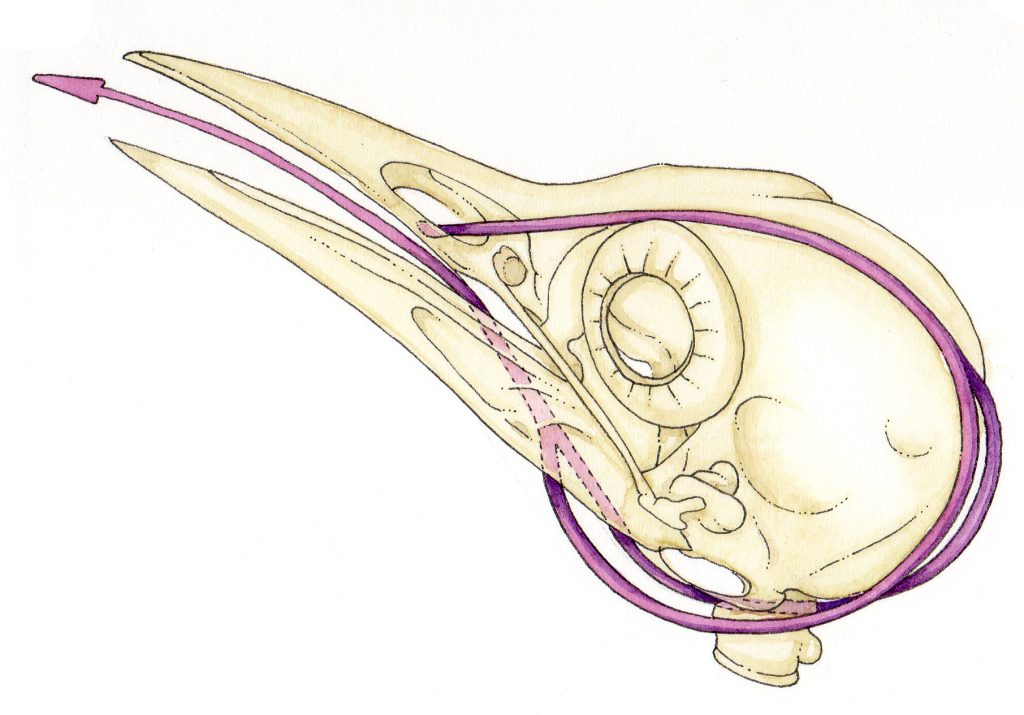

Woodpecker skull with the hyoid highlighted in purple

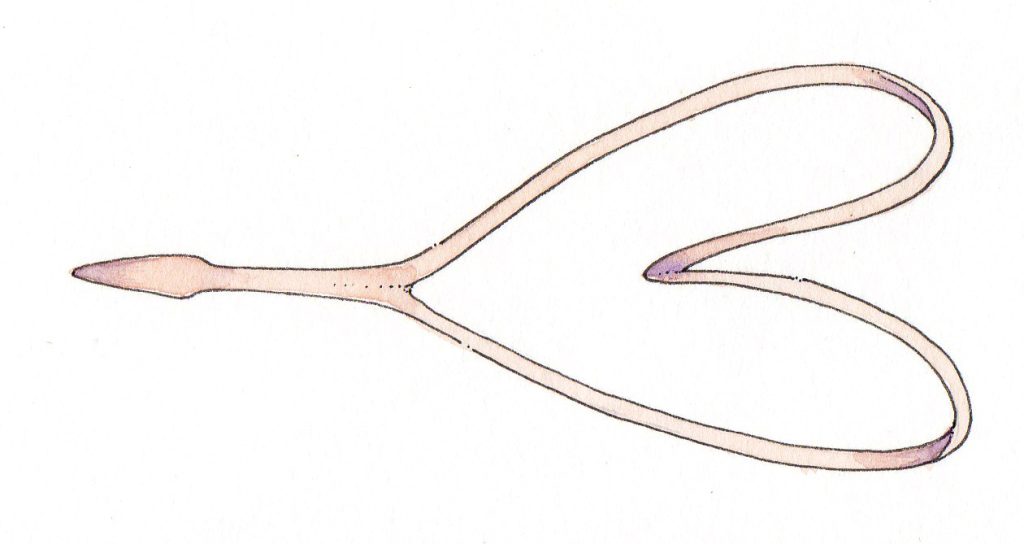

The hyoid is in the neck, and is present in all vertebrates. It’s made of cartilage, bones, and connective tissue. Hyoids help support the tongue muscles. In humans it’s pretty small, and shaped like the letter “U”. However, in birds it’s a more complex structure. Bird hyoids have two elongated arms which reach all the way round the skull and to the tip of the tongue, known as “hyoid horns”. (RSPB Spotlight Woodpeckers by Gerard Gorman, Bloomsbury, Sept 2018).

Woodpecker hyoid horns are especially long, and push the tongue out of the bill as they move forward. This means the woodpecker can extend its tongue a long way into holes in trees and cracks in bark, and thus successfully feed on the insects hiding in that habitat. The hyoid horns wrap around the skull, Keeping the hyoid structure in place, rather like a seatbelt or a harness might do.

The hyoid as a shock absorber

What’s especially clever is how the hyoid horns work when the tongue is not busy probing for insects. In the same way that shock absorbers can made a bicycle much smoother to ride, the hyoid in woodpecker cushions the skull from the force of the blows. It’s a highly elastic structure, so when it’s at rest it’s wrapped around the skull, like an elastic and protective cushion for the brain.

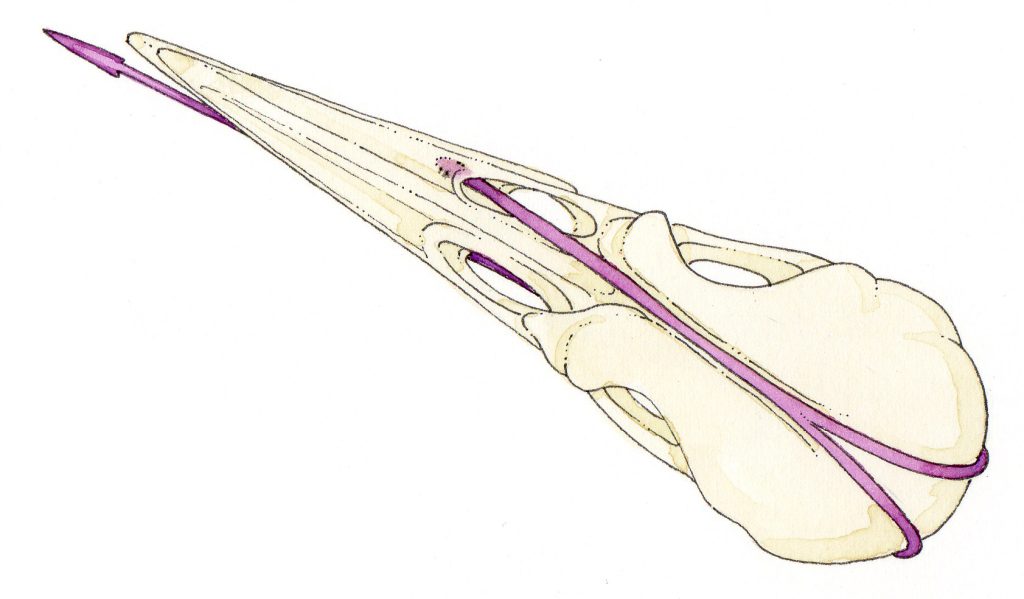

Woodpecker skull from above. This shows the hyoid is like a seatbelt round the back of the skull. It also shows the diagonal groove in the skull that it leaves.

Closer examination of the hyoid has found that it’s a jointed structure and has a tough inner core with a more flexible outer layer. It’s also been found that the posterior area of the hyoid bones have the lowest resistance to bending, which shows that area is highly flexible and thus perfectly designed to cushion impact. (“Structural analysis of the tongue and hyoid apparatus in a woodpecker” Jung, Naleway et al. Acta biomaterialia 2016)

The isolated hyoid

Other adaptations to avoid brain injury

Woodpeckers are also very good at using their beaks. They do this in a way that minimizes the impact on certain more vulnerable areas of their brains.

The beak design helps too, with the upper beak being slightly longer and harder than the lower beak. This provides something of a protective overbite, and the very hard upper beak helps absorb impact. It’s been proved these receive the bulk of the impact, with the force at a maximum just after a strike is made.

Great Spotted woodpecker combining behaviour and anatomy to avoid concussion

The plates of a woodpecker skull are more flexible than in other birds, with the bones in the forehead being more plate-like and spongy than in other parts of the skull. (“Structural analysis of the tongue and hyoid apparatus in a woodpecker” Jung, Naleway et al. Acta biomaterialia 2016)

Conslusion

All of these structural and behavioural elements combine to allow the woodpecker to drum against trees to find food. They drum to declare territories and attract mates. Repeated actions that would leave most vertebrates brain damaged can be performed over and over again with no ill effects.

Green woodpecker in open country

So next time you hear a woodpecker drumming on a tree, pause. Spare a thought for the extraordinary level of biomechanical skill that’s gone into making such behaviour possible. Over and over again, I’m gobsmacked by how wonderful and efficient evolution and natural forms are. Researchers are now looking to see if the physical adaptations of the woodpecker skull can be used to improve the design of bike helmets, and of other engineered structures that need to absorb energy.

Thank you for the very interesting article. I have a huge oak tree about 50 feet from my garden which is often home to hundreds of acorn woodpeckers. They visit my apple tree and bird bath daily.

During mating season, they fly into my plate glass window hour after hour and incredibly, it shakes the house. I have tried everything I can think of to deter them, but it goes on for days, and for hours at a time. I’ve often wondered why I don’t find dead woodpeckers under the window, but they seem to survive. Could this be due to the same protective mechanism that you describe? Do you know of any deterrent?

Oh my, that’s quite something. I’d imagine they’re trying to fight off other rivals for their territory ( ie their reflection) and yes, I bet it’s the hyloid structure that saves them from breaking their necks. I’m amazed your windows have survived! Have you tried putting up some of those window stickers of silhouettes of birds of prey? No idea if it would work or not, but I can’t think of what else to try!

Thank you for responding. I agree that it is most likely that the birds are seeing their reflection and thinking it’s a rival.

I did try hanging 5 black Silhouettes of crows and the attacks increased! I also taped ribbons, which blew with the breeze. This didn’t slow them down. And I hung bird netting, but then couldn’t stand the idea that the birds would get caught in it and took it down. The birds sit in my apple tree, about 10 feet from the window, and just dive into it.

I am glad to know that they are protected from this behavior. Wish I could say the same for my nerves. Thanks again.

Gosh,youve done everything anyone might think of! Poor you, Im nor surprised your nerves are in tatters! If I hear of any similar situations and amazing solutions Ill be sure to pass the info on. In the meantime, good luck!

X

Wow, this is truly fascinating! 🌳🕊️ I never knew much about woodpecker skull biomechanics until now. The natural history illustration really brings the subject to life. It’s incredible how these birds have evolved to withstand such high impact forces while drumming. Nature’s engineering at its finest! 🍃🎨 Would love to learn more about the research behind this illustration and how it helps us understand these incredible creatures better. Keep up the amazing work! 👏👍 #WoodpeckerSkull #Biomechanics #NaturalHistoryIllustration #NatureLovers

Thank you! Glad this got you interested.