Sedges, Grasses and Rushes: Telling the families apart

I recently went on another excellent FSC course, this time on identifying grasses (other grass courses by FSC available here). One of the first things to do is to figure out what makes a grass a grass, and not some other plant. In most cases, it’s sedges and rushes that can lead to confusion, so this blog hopes to use the chart below to untangle these groups.

The chart is very closely based on one provided by the course tutor, Fiona Gomersall.

Do remember that this is a brief overview. To get into the details of these fabulous plants you really need to work through keys and use clear identification guides. Lots of other sites have more on this, check out Nature’s calender, BCWF Wetlands video, Naturespot’s gallery of photos, and the BSBIs guide to grass resources.

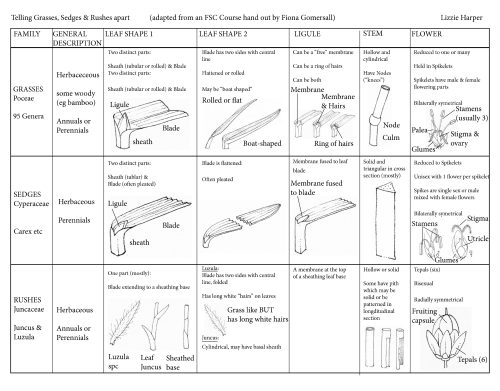

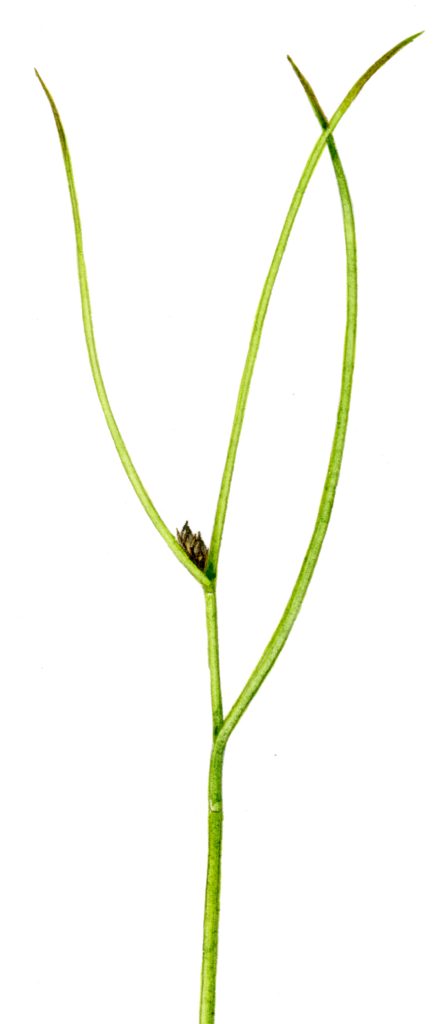

Comparison table

This table compares the leaves, ligules, stems and flowers of Grasses, sedges, and rushes. For more on each group, please check out past blogs: Grasses, Sedges, Rushes.

Although it looks pretty overwhelming at first sight, it’s actually not too bad. And it’s great to have all the information together in one place. The general description is something we won’t be looking too closely at, and whilst trying to identify and key out grasses on the course, deciding if a species was an annual or a perennial proved quite a challenge! I guess it does show that if you have something that looks like a grass but is woody (like Bamboo, Bambusa vulgaris), then it’s going to be a grass species.

Leaf shape: Grass

Grasses have leaves made of two clearly distinct parts. There’s the blade, with it’s parallel veins and often with a central rib or keel. Then this folds, and surrounds the stalk of the grass. This enclosing part of the leaf is called the sheath. Sheaths can be open, with a clear slit, or fused shut, like a tube.

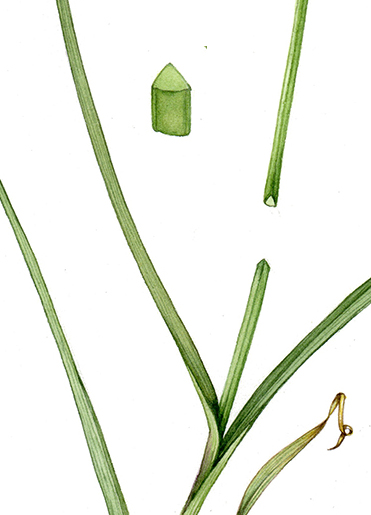

Common bent Agrostis capillaris

Here’s a close up of the blade and sheath of another grass, Cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata. Grass blades vary in shape enormously. Think of the broad and flat leaves of the Common reed Phragmites australis in comparison to the wiry needle-like leaves of something like Mat grass Nardus stricta. Some grasses leaves grow rolled, and will emerge and may flatten out at maturity. Other leaves don’t flatten out, but remain needle-like through life (like the Fescues). Other blades grow as flattened, laterally compressed shoots. The easiest to bring to mind is Cocksfoot.

There are also ligules in the mix, thin (mostly) membranous structures at the fold between sheath and blade, but we’ll come back to them in a bit.

Leaf shape: Sedge

The leaves of sedges also have the same two distinct parts. The blade, and the sheath. The sheath is fused closed in all but one small African genus of sedges. The blade is often “pliate”, or pleated. This means that if you took a cross section of a sedge leaf it might look a little like a zig-zag.

Glaucous sedge Carex flacca

Below is a close up of the blade and sheath of the Dioecious sedge Carex dioica. The sheaths are fused closed. As with grasses, the shape of the leaf blade varies enormously. Some sedges have very thin, needle-like leaves whilst others like the common garden plant, Pendulous sedge Carex pendulosa, have broad ones. Colour varies too, from the almost blue leaves of the Carnation sedge Carex panicea to the bright yellow-green of the Long-stalked Yellow sedge Carex lepidocarpa.

Dioecious sedge Carex dioica

Leaf shape: Rushes

Rushes generally only have one part to their leaves. The blade doesn’t have two distinct zones, but simply extends to a sheathing base around the stem. However, there’s a lot of variety in the rushes leaves, mostly dictated by whether they are Juncus (rush) or Luzula (wood-rush) species. I don’t think a true rush would be easily mistaken for a grass, they have a very different feel, and their leaves are round and needle like, and cylindrical in cross section.

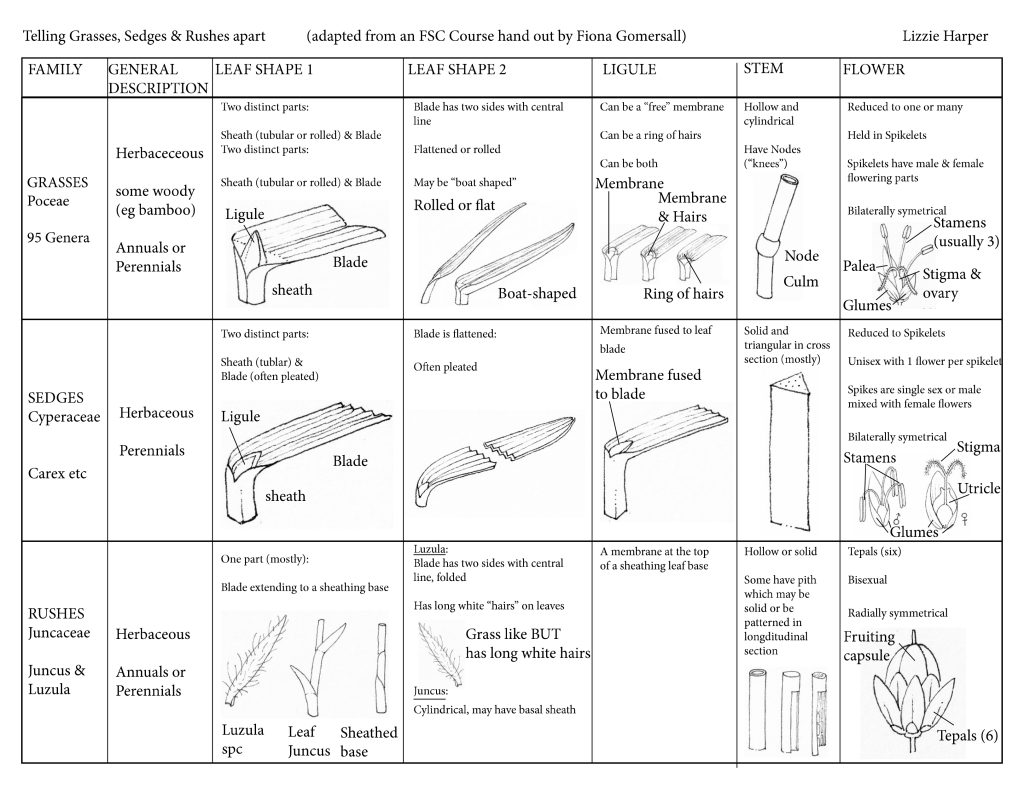

Blunt flowered rush Juncus subnodulosus

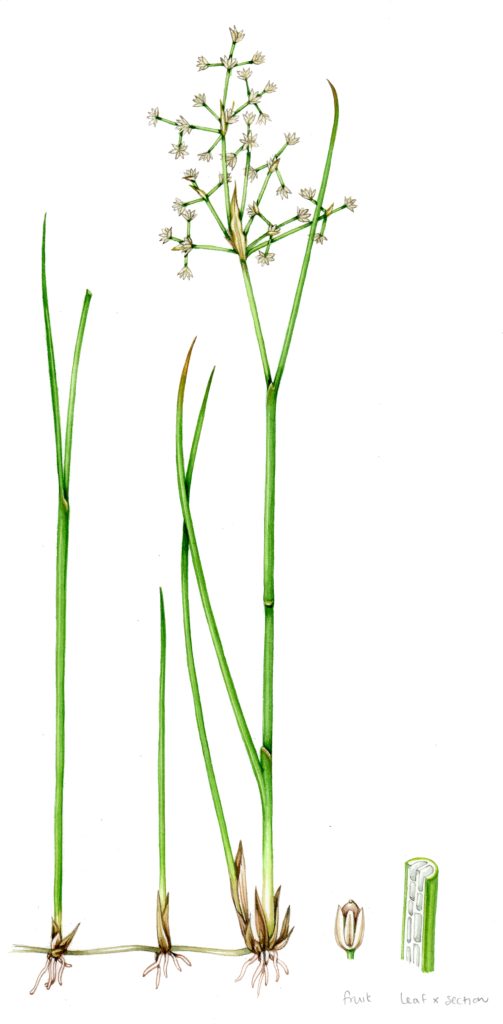

Below is a close up of the leaf and sheath of another of the Juncus rushes, Three-leaved rush Juncus trifidus. As you can see, there’s no clear definition between the blade and the sheath, the two blend into one.

Three-leaved rush Juncus trifidus

The Wood-rushes are a little trickier as they have wider leaves and it can be hard to see if they have blades and sheaths or not, because the leaves are often low down on the plant. The big give away with the Wood-rush leaves is the long white hairs. All Wood-rush leaves have these, and they are very distinctive. I don’t think even the hairiest of sedges or grasses produces leaves with these distinctive long, silky leaf hairs.

Greater wood rush Luzula sylvatica

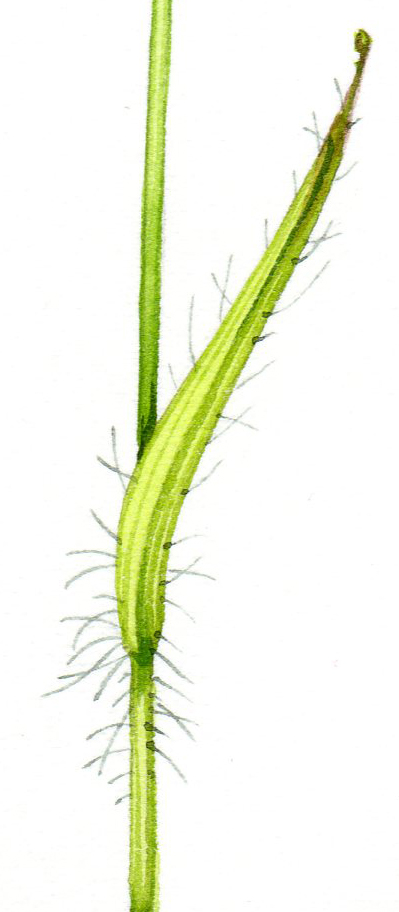

These hairs are also apparent on the stem. Below is a close up on the leaf of the Hairy wood rush Luzula pilosa.

Leaf of Hairy wood rush Luzula pilosa

Ligule: Grasses

Ligules are structures at the junction of the leaf and the stem. They are mostly membranous in grasses, although sometimes will be replaced by a ring of hairs (as with the Common reed). Sometimes they have hairs and membrane, and there’s a whole lot of variety in the shape of ligules. They can be pointed or rounded, long or short, smooth or torn. Ligules of grasses are often “free”, unfused to the leaf blade.

Marram grass Ammophila arenaria

Marram (above) has a long and pointy ligule which is really easy to see. (It’s worth noting that Marram is one of the grasses we mentioned sporting rolled leaves, which you can see here in cross section.)

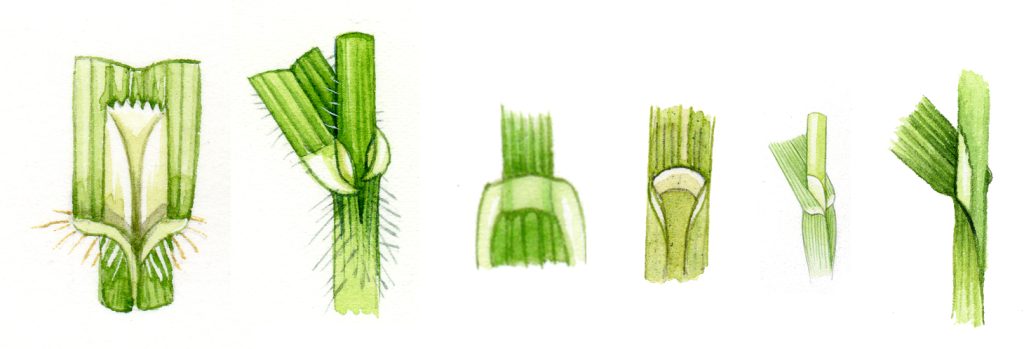

Below is an array of grass ligules to show their variety.

Grass ligule variety

Some cling closely around the stem, others are much looser. Some are thin crescents of membrane, others are far more substantial.

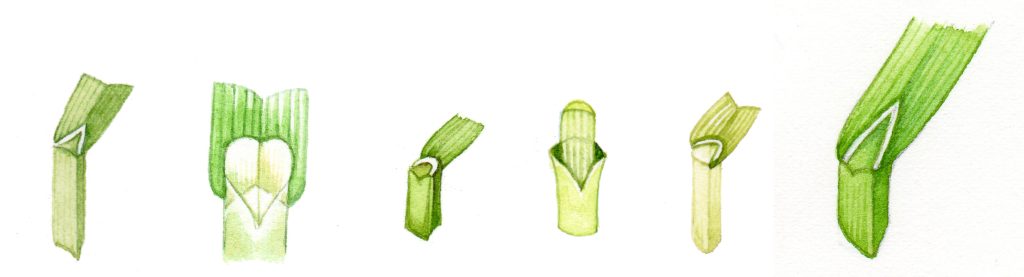

Ligule: Sedges

Sedges also have ligules. these tend to be less obvious, and are never free. In all cases, sedge ligules are fused to the leaf blade.

Sedge ligule variety

However, like grasses they have a variety of shapes. Some are pointed, some are rounded. They too are membranous.

Ligule: Rushes

Rush ligules are membranes at the top of a sheathing leaf base. These tend to be really small and inconspicuous. Checking through all my illustrations of rush species, I can’t find any where the botanist has asked for a close up of a rush ligule.

Stems: Grasses

The stems of grasses, sedges and rushes are possibly the quickest way of telling them apart. They are also at the root of the common botanist’s ditty, “Sedges have edges, rushes are round, grasses have knees from their tips to the ground”.

So what exactly does “having knees from their tips to the ground” mean? It refers to the nodes. Nodes are found in all grasses, between the sections of the stem (or “Culm”). Often the growth direction may change at a node, although this is far from inevitable. Nodes may be flushed with colour. In the Meadow foxtail Alopecurus pratensis, the nodes are ochre. In some species they’re purple. Some grasses have smooth nodes. Others are thick with hairs, or positively velvety like the Creeping soft grass, Holcus mollis.

Grasses have nodes. Sedges and Rushes do not.

Variety of grasses nodes

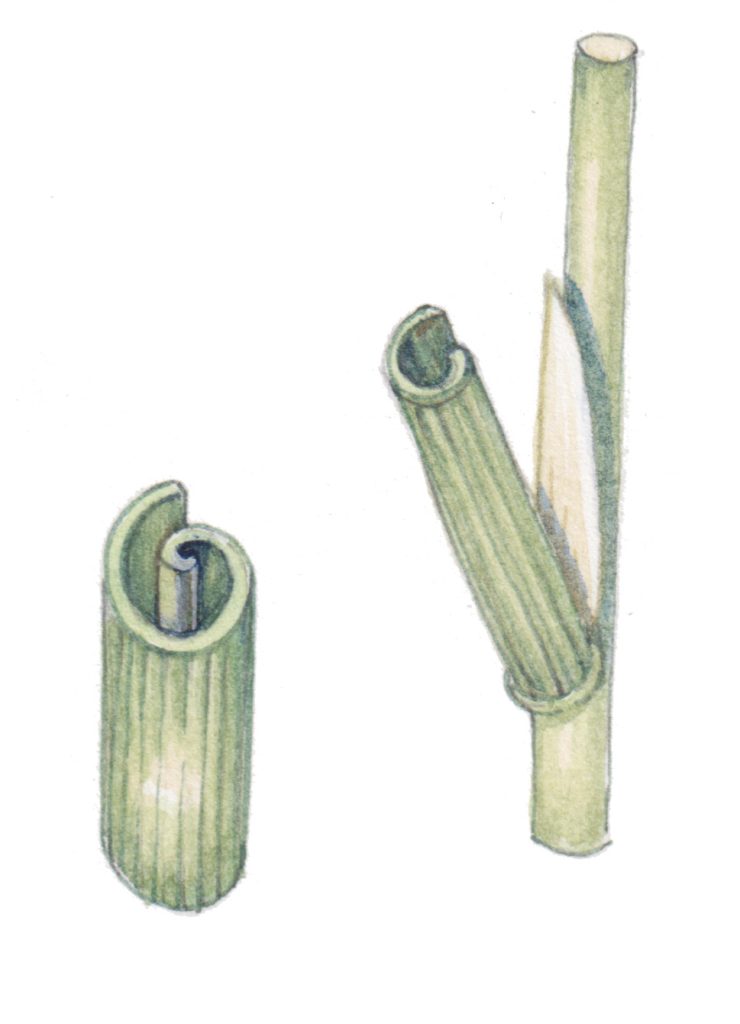

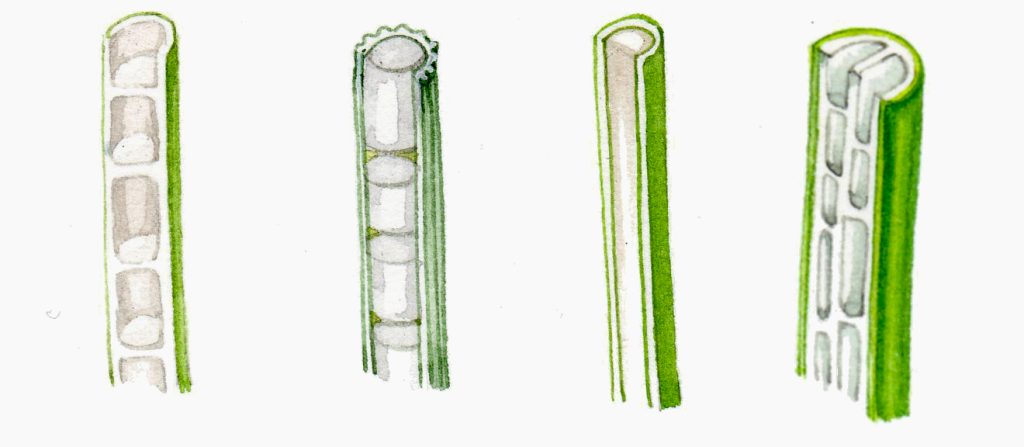

The other important point to note is that all grass stems are round in cross section, and hollow. Rush stems are also round, but not always hollow. And the stems of sedges are altogether rather different.

Stems: Sedges

Sedge stems are wonderfully triangular in cross section. They are also solid, not hollow in most cases. So a good way to check to see if you have a sedge is to run your fingers up the stem. if it feels like there are edges there, it’s a sedge. You can go to the trouble of taking a cross section of the stem, but sometimes sedge stems aren’t “in your face” triangular, so you may be disappointed.

Detail of the stem and cross section of Greater Tussock sedge Carex paniculata

And there are no nodes.

Stems: Rushes

Rushes have cylindrical, round stems, like the grasses. However, they never have nodes. And in many cases they have supporting internal structures, pith. this may fully fill the cavity in the stem, or be distributed in species-specific patterns. These can be seen if you take a longditudinal section down a rush stem. Some rushes also have lateral pithy supports. These can be felt clearly is you run your fingers up the stem. They’re known as the jointed rushes and include species like he Sharp-flowered rush Juncus acutiflorus.

Sharp Flowered Rush Juncus acutiflorus

Below is a selection of rushes in cross section. All are members of the Juncus rather than the Luzula tribe. The spaces between the pith are air pockets.

Cross sections of Juncus rushes

So you can see that using the stems as an instant diagnostic between grasses, rushes, and sedges can be incredibly useful. Nodes are grasses. Edges are sedges. And round stems without nodes are going to be rushes.

Flowers: Grasses

Now, when it comes to the structures of the flowering parts of these three groups, it’d be very easy to go down an anatomical rabbit hole. I’m keen to avoid this. For more on the botany and structures of grasses flowers, sedge flowers, and rush flowers, check out the relevant blogs I wrote a while ago.

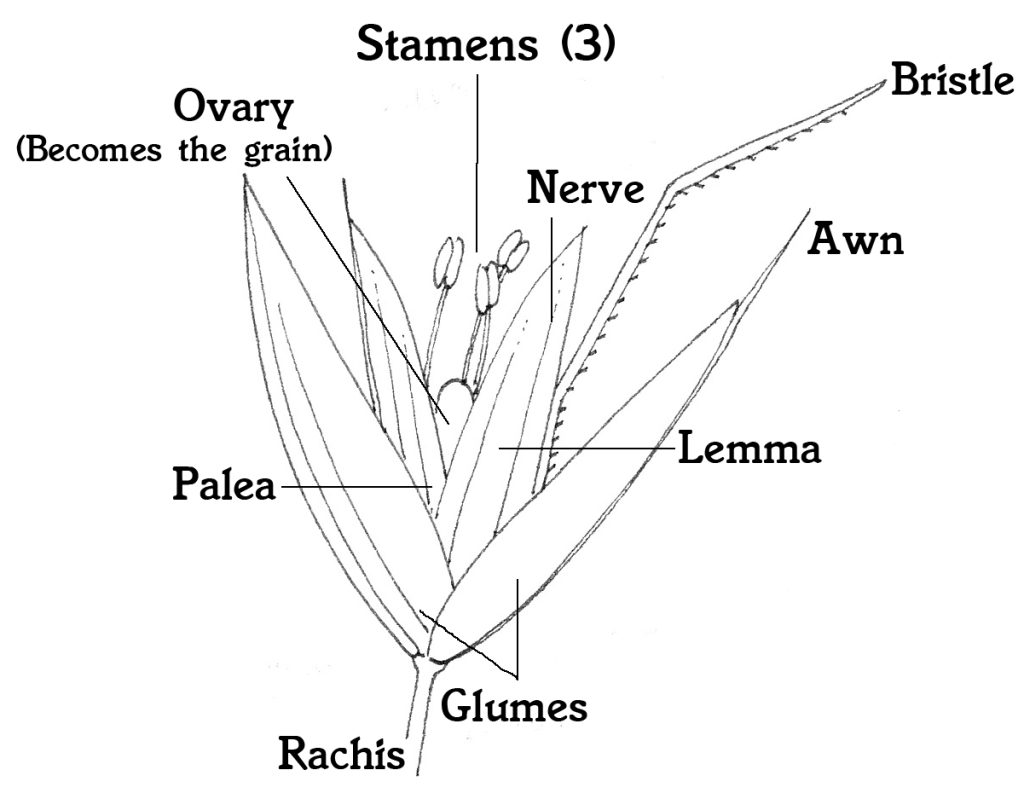

Grass flowers can be single or held in assemblies known as spikelets. The way these are arranged on the stem is important when it comes to species identification, some will cling close to the stem (like Rye grass, Lolium perenne), others will be on the end of long branches (like Hairy wood brome Bromopsis ramosa).

Hairy wood brome Bromopsis ramosa

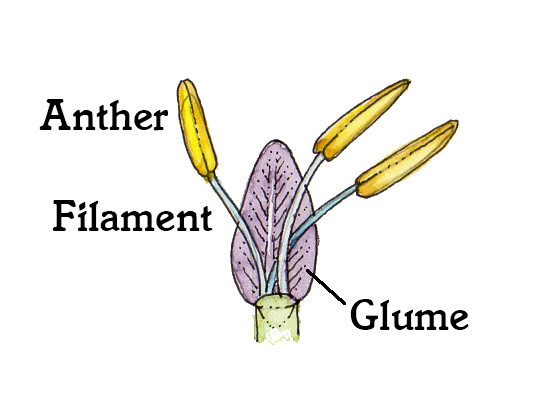

All spikelets have male and female flowering parts. The male parts are stamens, often with drooping anthers. There are usually three stamens. This helps the wind disperse the pollen. The female parts are the ovary and two long feathery stigma (to catch that pollen). The flowering parts are held within papery scales called glumes and lemma, and within these another scale called the palea. Don’t worry too much about all of this. The take home message is that grass flowers have male and female parts in one place. And that they are bilaterally symmetrical.

The diagram below shows the outer “scales” that surround the flowering parts as well as the stamens and ovary. I’m assuming I intended it to show a fertilized flower, or there would also be stigma coming from the ovary. The spikes that in some grasses come from the glumes are called awns and deserve a blog of their own as they vary enormously from species to species.

Grass spikelet structure

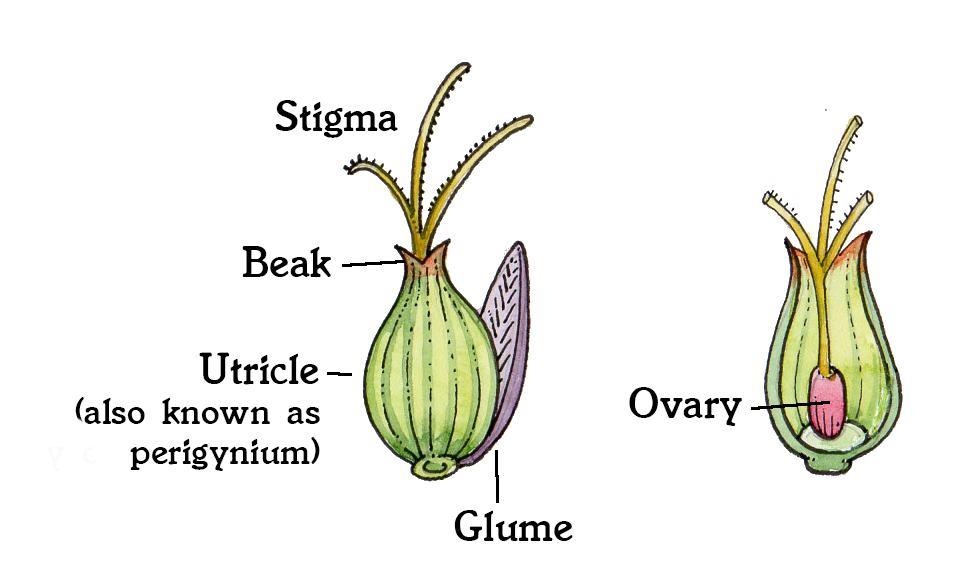

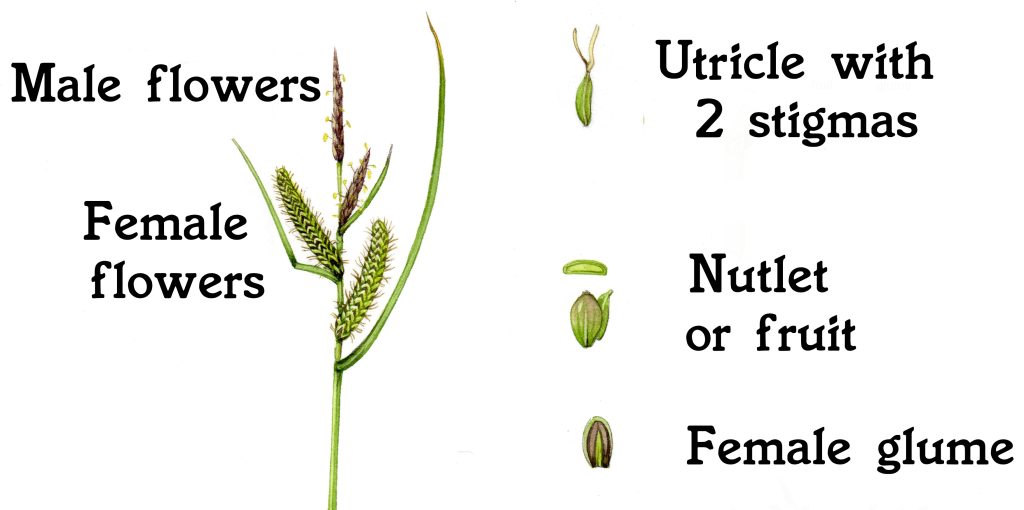

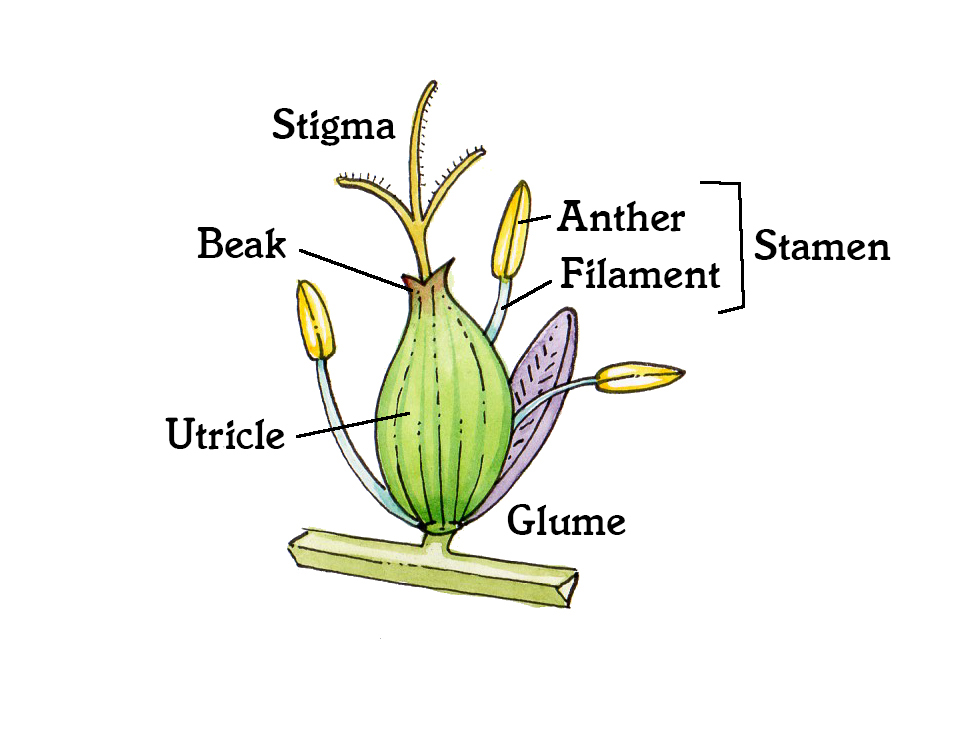

Flowers: Sedges

Sedge flowers are either unisexual male or female. Or, in some groups, bisexual, having female and male flowering structures together. Often all the male flowers will be held in one spike, and the females in another spike. these are frequently on the same plant. Don’t be fooled by the unisexual flowers though, you will sometimes have sedge species where female and male flowers are held in the same flowering spikelet (like the Brown sedge Carex disticha). But if you look closely at the flowers of these unisex species, each individual one will have either all male parts or all female parts.

Female (above) and male (below) sedge flowers

Like the grasses, these flowers are enclosed in glumes. Unlike the grasses, the female flower sends stigmas out from the Utricle, a vase-like structure which develops into the seed if fertilized. Female flowers come from utricles which have two or three stigma. this helps identify species, so be aware of it.

Sedge with Unisexual flowers, Common sedge Carex nigra

You can tell the spikes of male flowers from the spikes of female flowers without too much trouble. The male flowers tend to be far thinner, and are often above the fatter female flowers (see above). Although not always. And be careful! Sometimes unisexual male and female flowers are all mixed in together! An example of this is the Brown sedge, Carex disticha.

Brown sedge Carex disticha

Other sedge species have bisexual flowers, like the grasses. Cyperus Umbrella sedges bear bisexual flowers, as do the spike rushes, Eleocharis. For more on sedge flowers check out this blog from plant i.d. net.

Few flowered Spike rush Eleocharis quinqueflora

These spike rushes are rather confusing because they look so different from other members of the sedge family, but they are instantly recognizable. Unlike true rushes, they too hold their flowers within glumes.

Diagram of a sedge bisexual flower

Flowers: Rushes

You’ll be relieved to hear that rush flowers are rather simpler than sedge flowers. All are bisexual. Unlike grasses and sedges, their flowers are held within six “tepals”. These tepals are not petals, although they might be mistaken for petals. The difference is that petals are part of the corolla, and separate from sepals, the bits that you can often see lurking behind petals and which make up the enclosing bud before flowering. In some plants, like rushes and tulips, there’s not distinction between a petal and a sepal. So these structures are called Tepals. Easy once you know! And think about it, tulip buds aren’t encased in green sheaths are they? It’s cause the whole flower is built of tepals, not sepals and petals.

Back to the rushes!

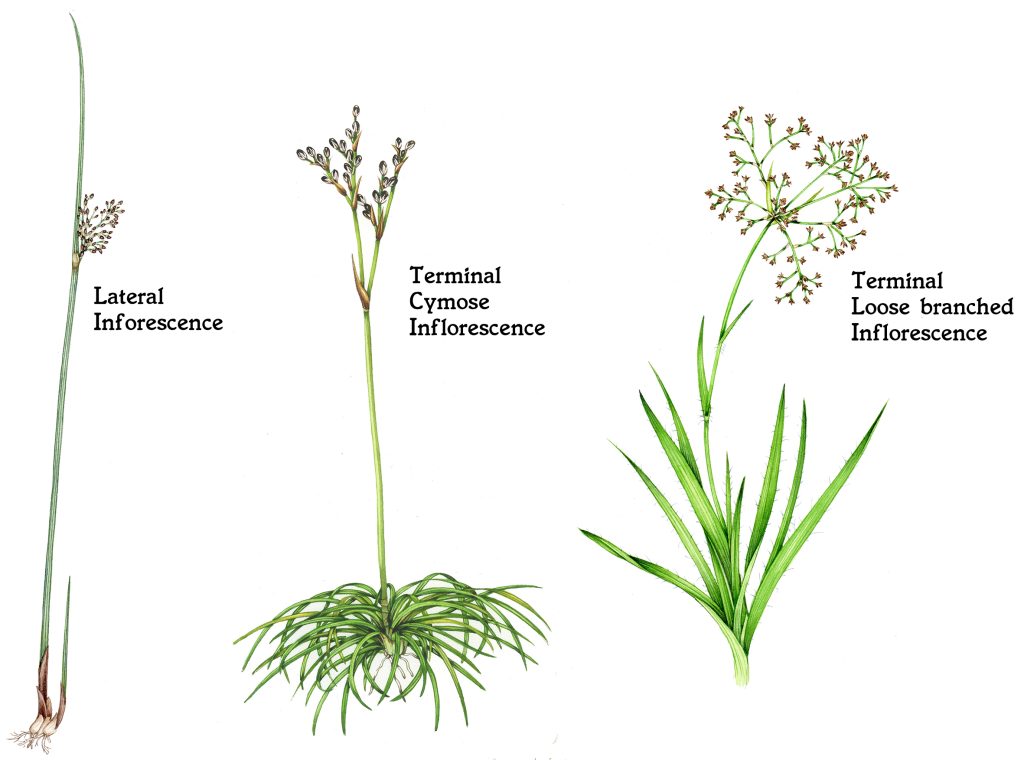

Rush flowers can be carried at the top of the stem, come out the side (like the Hard rush Juncus inflexus and the Soft rush Juncus effesus), or even be carried in the junction between stem and leaf. This is the case for the Three-leaved rush Juncus trifidus. The hard rush on the left, Juncus inflexus, bears lateral flowers. the Heath rush Juncus squarrosus has its flowers in a tight flowering head at the top of the plant. The Greater Wood-rush Luzula sylvatica bears its flowers in a much floppier and looser terminal flowering head.

Three rushes showing different patters of flowering

Individual rush flowers are not bilaterally symmetrical like the flowers of grasses and sedges. They are radially symmetrical.

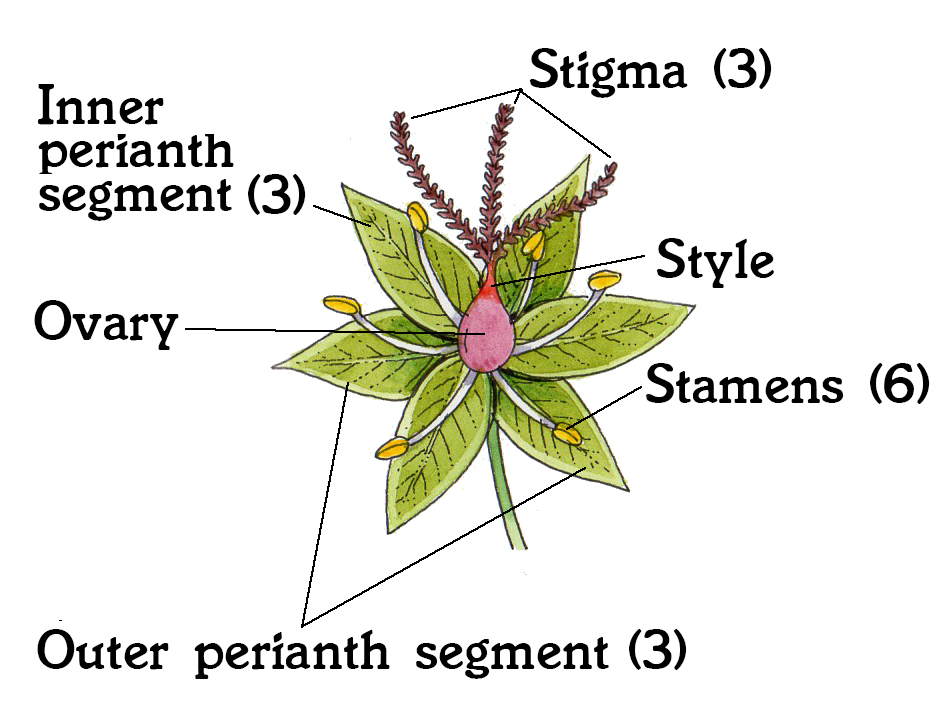

Flowers are the same structure in a true rush flower (Juncus) or a Wood-rush flower (Luzula). Below is a close up diagram of a Juncus flower. You can see it has 6 tepals, 6 stamens, and a central female flower with 3 stigma. Don’t worry about the perianth stuff, it’s another name for the tepals.

Rush flower

Flowers of the Wood-rush are similar, but often feel more star-like and open. However, the underlying radially symmetrical structure is the same.

Conclusion

So there you have it! Lots of pointers on how to tell your grasses, sedges, and rushes apart. I still think the rhyme about “sedges have edges…” is the easiest way in. But inevitably, once you get out in the field and start looking at all these plants, telling them apart will become easier and easier.

it’ll also give you a chance to crawl about on your knees being awed by how stunning all of these often over-looked plants are!

Very clear explanation

Phew! I always worry that I might end up making it mroe rather than less complicated. So thankyou.

Well, I knew nothing about this subject, even being a keen gardener, now I know a vast amount more and have some excellent illustrations to boot.

Thank you Lizzie.

Hope all is well there.

Regards Peter

Thank you Peter, that’s such a lovely accolade. I appreciate it

Wohh exactly what I was looking for, thankyou for posting.

So glad to hear it

Indeed, distinguishing between grasses, sedges, and rushes can initially seem daunting, but with practice and observation, it becomes easier over time. While the rhyme “sedges have edges” is a helpful mnemonic, hands-on experience in the field is invaluable for refining your botanical skills. As you spend more time exploring and studying these plants up close, you’ll develop a keen eye for their unique characteristics and be able to identify them with confidence.

Thanks wpg

I agree entirely with your encouragement, it does get easier with time and practice!

Yours

Lizzie