Trees: Scots pine Pinus sylvestris

Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris

Scots pine is one of a series of blogs I’m writing on common British trees. You can also see blogs on the Elder, the Yew, the Ash, the Oak, the Holly, the Sycamore, the Rowan, the Hawthorn, the Birch, the Lime, and the Beech.

The Scots pine is one of only three native UK conifers, along with the Yew and the Juniper. It grows wild in heathland and in the Caledonian pine forests of the Scottish Highlands, although only 1% of these remain. About 7000 years ago it was the commonest tree in Britain but suffered when the climate got wetter and warmer and then again when it was cleared for grazing. Instantly recognizable, it is used for timber and provides a haven for birds, insects, and mammals.

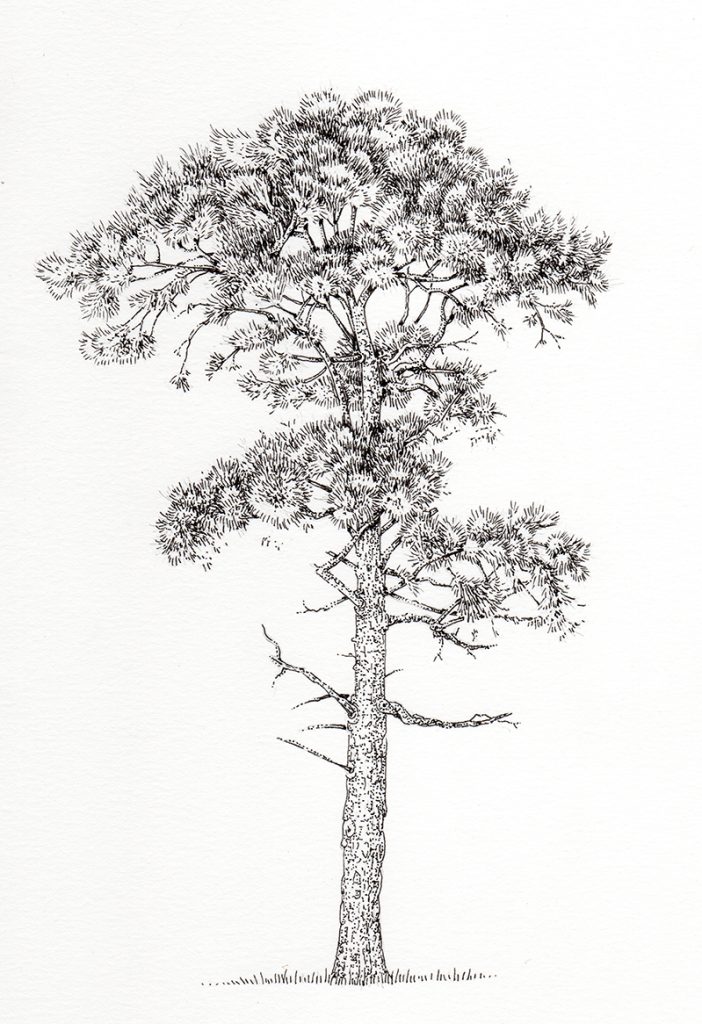

Scots pine Pinus sylvestris tree

Identification: Tree shape

Scots pine grow to 35m tall and have a domed or flattened top and can live for 700 years. They shed their lower branches as they grow, leaving distinctive broken limbs below the main crown.

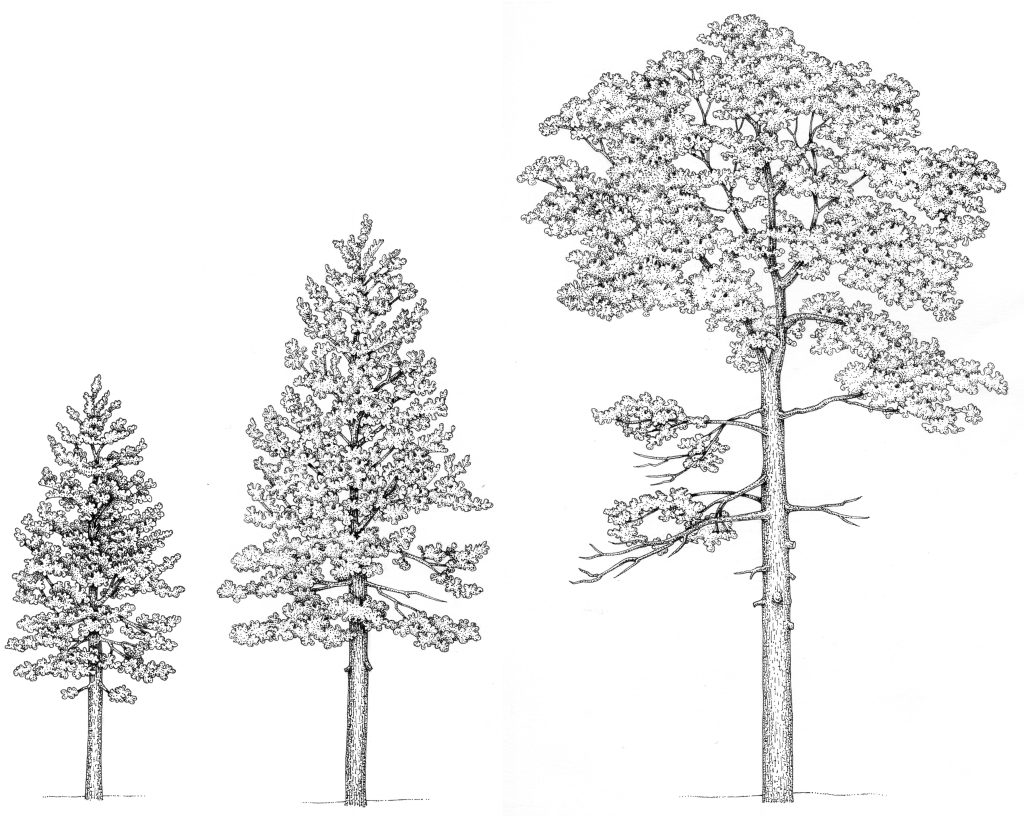

Scots pine Pinus sylvestris tree growth progression

These trees grow in poor soils from sea level to 2,400m and were briefly extinct south of Scotland in the 1600s before being re-introduced to parkland and heaths.

Identification: Leaves

Scots pine have slightly twisted paired needles. These are a grey green and grow to 10cm in young trees. As the tree ages, the needles grow to shorter lengths, in the region of 3 to 7cm long. They are evergreen, and linear.

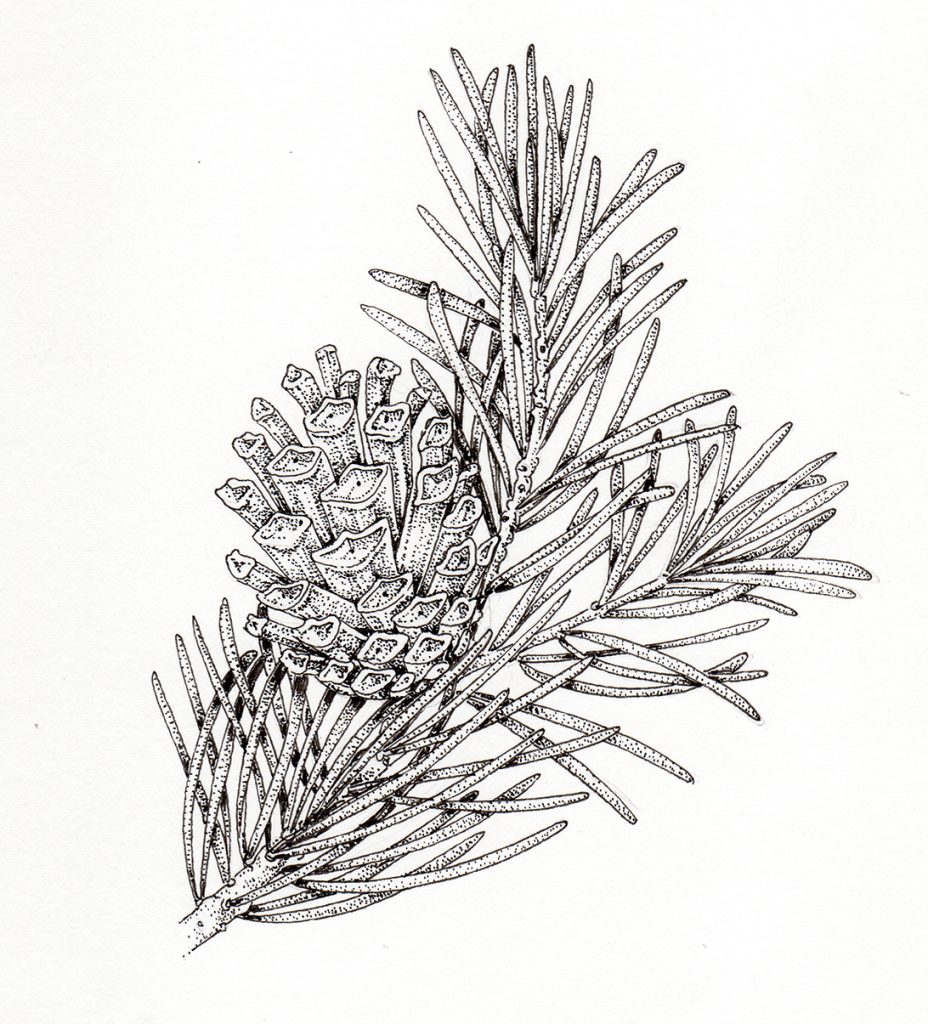

Sprig of Scots pine

Identification: Flowers

The flowers of Scots pine are monoecious, meaning male and females are borne on the same tree. The female flowers grow on higher more exposed branches where they can catch the male pollen, carried by wind. They are reddish purple and grow on the tips on new shoots, looking like tiny pine cones.

Scots pine female flower (strobilus)

The male flowers are clusters of yellow pollen-producing anthers, growing at the base of the shoot.

Scots pine male flowers

Scots pine tend to flower in May, filling the air with clouds of pollen.

Identification: Fruit

The fruit of the Scots pine is a cone. These develop from the fertilized female flowers and start off as green. The cones take two years to mature and are 3 to 6cm long. A Scots pine will bear cones of different ages simultaneously – young green ones and larger older grey ones. Mature woody cones have a raised bump at the centre of each cone scale. Within the cones are the seeds, and once mature the cone scales open to release the winged seeds.

Mature cone

Identification: Bark and buds

The bark of the Scots pine is reddish but becomes fissured and darkens to near black with age. This explains why the tree looks like its tree trunk is two coloured, rusty red at the top and black at ground level.

Twigs are hairless and green, and the plant has sticky buds borne on the tips of yellowish twigs.

Similar species

There are other pines grown in Britain, many in forestry plantations rather than in the Caledonian forests or on heathland. The bi colour of the bark makes the Scots pine distinctive. The other native evergreens, the Yew and juniper, are very different from the Scots pine. The former has glossy dark green needles and a flaky brown bark and the juniper has needle-like leaves and grows low to the ground. They bear soft red and dark purple berries respectively, rather than woody cones.

Juniper Juniperus communis

History: Folklore

The Scots pine has been voted the national tree of Scotland and figures on coats of arms and clan motifs. Clan chiefs would be buried under Scots pine trees and in the Norse countries, great warriors were buried on land in boats made from pine wood.

History: Mankind and Scots Pine wood

Scots pine were planted near isolated farms in the north as wind breaks, and stands of them were planted to help travellers with navigation on bleak moors and heaths.

The wood is a strong softwood and is used in the construction industry, and to make telegraph poles, gates, fenceposts and pit props in mines. It has also been a source of charcoal.

Jackdaw on ancient Scots pine fence post

Rope can be made from the inner bark, tar derived from the roots, and a dye from the pine cones. The cones were also dried and used for kindling. Finally, turpentine can be made by tapping the tree for resin.

History: Food and Medicine

Although pine needles are edible, they are pretty tough and better used for flavouring. Some evidence suggests that they can induce miscarriage, so shouldn’t be eaten by pregnant women. They can flavour sugar, syrups and alcohol. Steaming vegetables over water full of pine needles can give a piquant flavour, and they can be made into teas.

Cones and needles

Scots pine needles are rich in vitamin C and can be nibbled to quench thirst, or drunk in teas to fight asthma and fatigue.

There are unsubstantiated claims that pine pollen helps prevent aging. Liniments of pine are used on sore joints, diluted pine oil can banish head-lice, and pine tar can help treat skin problems. The scent of pine helps clear blocked noses and is good for respiratory problems.

Scots pine and Wildlife

In the Caledonian forests, rare birds like the Capercaille live along with Scottish wildcats and plants like the Lesser twayblade. The forest floor is home to ants including the Scottish wood ant.

Worker ant Formica aquilonia Scottish wood ant

Red squirrels chase each other around their trunks and Pine martens chase the red squirrels.

Pine marten Martes martes

Flocks of Crossbill and small passerines feed there. Golden eagles and Osprey nest in the crowns of the trees. They provide vital shelter for so much wildlife, as seen in this blog from Loch of the Lowes.

Threats

Various diseases like Heterobasidion annosum affect the Scots pine causing root rot and butt rot. Pine stem rust, red-band needle blight, and needle cast disease also occur. The trees suffer attacks from the pine wood nematode which causes pine wilt and Fusarium circinaum, a disease that leads to tree canker. Some of these pathogens are recent arrivals and pose real threats to the trees, although the University of Nebraska suggests pine wilt can be prevented by injecting healthy trees with abamectin or emamectin benzoate. For more on the threats to Scots pine, check out the article in The Guardian newspaper.

Canker (in this case on a rose not on a Scots pine)

A potential threat in future years is the Pine processionary moth Thaumetopoea pityocampa whose range is expanding northward due to global warming.

They may also be defoliated by the Pine tree lappet moth Dendropinus pini. Migrating north from the European mainland, a breeding colony was detected in Scotland in 2009 and containment regulations are in place to try and contain its spread (Scottish Forestry).

Conclusion

The Scots pine is an easy recognised native conifer. Despite challenges facing the tree, mainly caused by invasive species moving northwards thanks to global warming, for now it is common on uplands, heathland, and in forestry. Providing timber and protection for wildlife, it is to be hoped that it will continue to thrive for centuries to come.

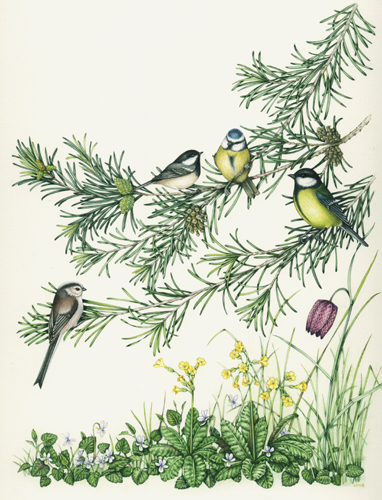

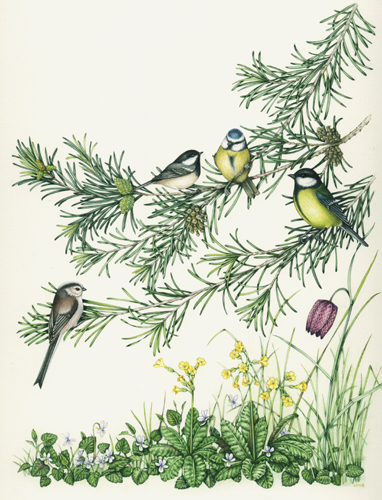

Long-tailed, Blue, Coal and Great tit in a Scots pine

Online sources for this blog include websites of the Woodland trust, Kew Plants of the World , Trees for life, Tree guide UK, and NatureSpot. Reference books for this blog include the excellent The Greenwood Trees by Christina Hart-Davies and the Reader’s Digest The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain (out of print but commonly available second-hand). I also referred to The Tree Forager by Adele Nozedar and The Living Wisdom of Trees by Fred Hageneder.

Absolutely fabulous illustrations. The detail is incredible. We look forward to seeing your blogs.

Aww thanks Jackie, that’s such a lovely thing to hear