Bantham Sand Dunes Landscape

A recent commission for South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty involved creating an idealised landscape of Bantham Sand dunes. This blog will highlight some of the species included in the illustration, and show the work that goes into including all the species needed in one view.

Planning the illustration, and roughs

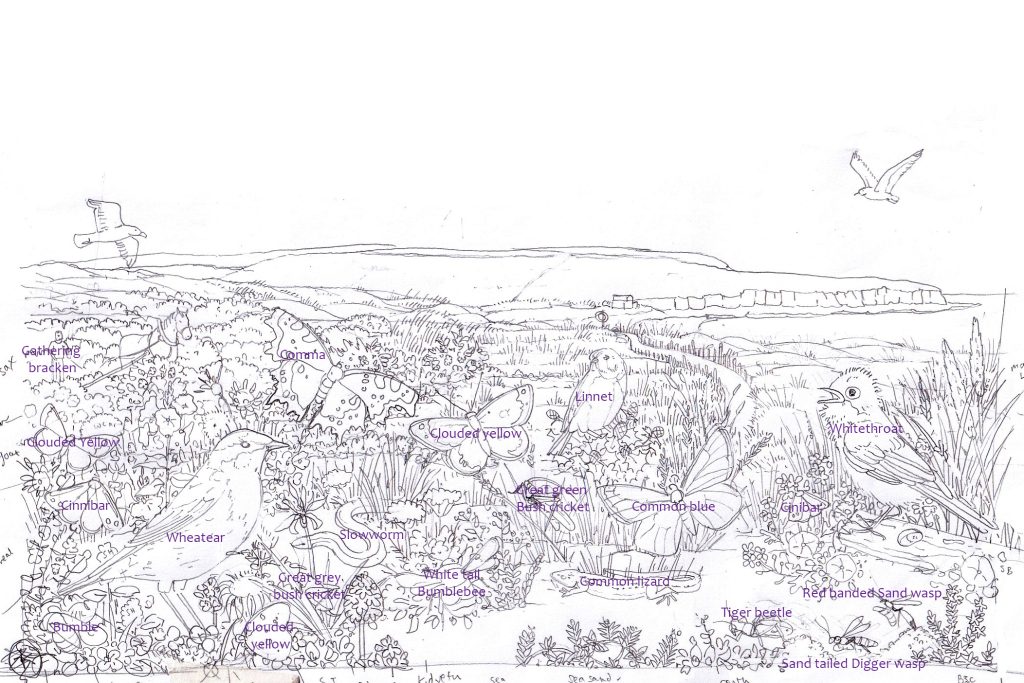

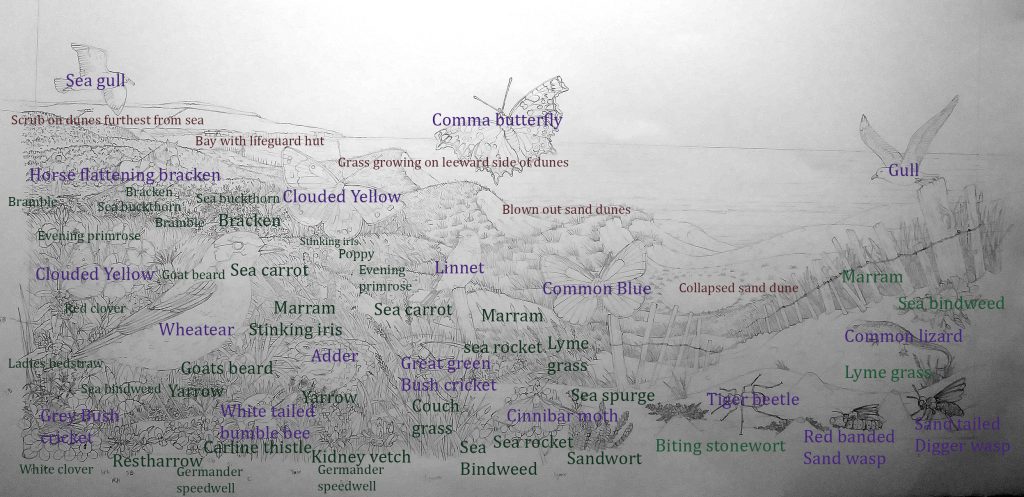

The species list for this commission was imposing. There are 28 plant species, and 17 animals pictured. There’s also the concept of succession – plants prevent dunes from eroding and the habitat ends up as a stable thicket of brambles, evening primrose, wild carrot and other dune species. Management practice is included too, with the volunteer controlling bracken with a horse-drawn roller.

I begin by drawing up and submitting a rough illustration, then a detailed pencil drawing which I annotate so the client can see where each species will sit.

Unfortunately, there was a change of focus, and the detailed drawing had to be re-done, making sure the succession and establishment of stable dunes was the main visual message.

This time, the illustration (65cm x 40cm) got the go-ahead. In this annotation, ecological and management constraints are in dark red. Animals are in purple. Plant species are in green. Let me lead you through some of my favourite parts.

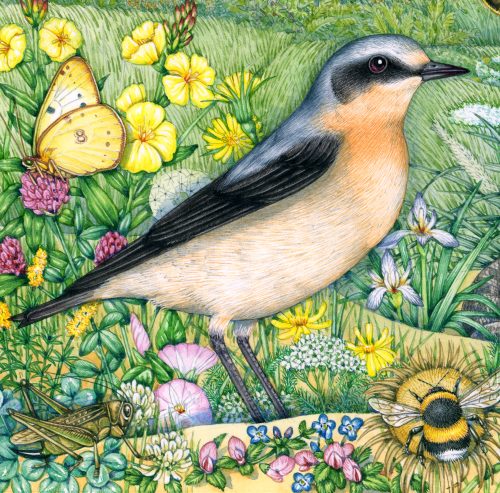

Birds: Wheatear

The male Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe (pictured here) is a delicate colour, with a pale peach chest and distinctive black eye stripe. It’s name refers to its’ white rump, which has a black “T” on it. The Wheatear is a migratory passarine. It spends its’ winters in tropical Africa, but comes north in summer to nest.

Spending much of its’ time on the ground, the Wheatear nests in holes amongst rocks, and young emerge after a couple of weeks. They learn to fly soon after. Wheatears feed on invertebrates. Their call is a mix of high whistles and chattering.

In this illustration you can also see a Clouded yellow butterfly, a Great grey Bush cricket, and a White-tailed bumble bee. Plants include Evening Primrose, Goats’ beard, red and white clover, Lady’s bedstraw, Restharrow, Speedwell Yarrow, Carline thistle, and Stinking iris.

Birds: Herring Gull

This illustration doesn’t feature many birds. A Whitethroat was removed at an early stage, leaving only the Wheatear, Linnet, and a couple of Gulls.

I loved painting the summer shadow on this Herring Gull Larus argentatus. The purple-blue shadow reminded me of summer days, and the yellow beak with scarlet spot made for the perfect contrast. It’s a small part of the illustration, but I quite like it. To balance the beak spot I slightly bumped up the pink on the legs, in reality they are a little paler than this.

Herring gulls are common along coastlines, and in city centres. They exploit our refuse dumps, and farming practices as well as the fishing industry. Bold birds, they have been known to steal food from holiday makers’ hands, and are vocal. I regard them as admirable survivors in a world which is increasingly anthropo-centric.

Other gulls to look out for on the coast are the Great and Lesser black-backed gull , and the Kittiwake. Make sure you look closely at the colour of the legs, this can be vital in telling species apart.

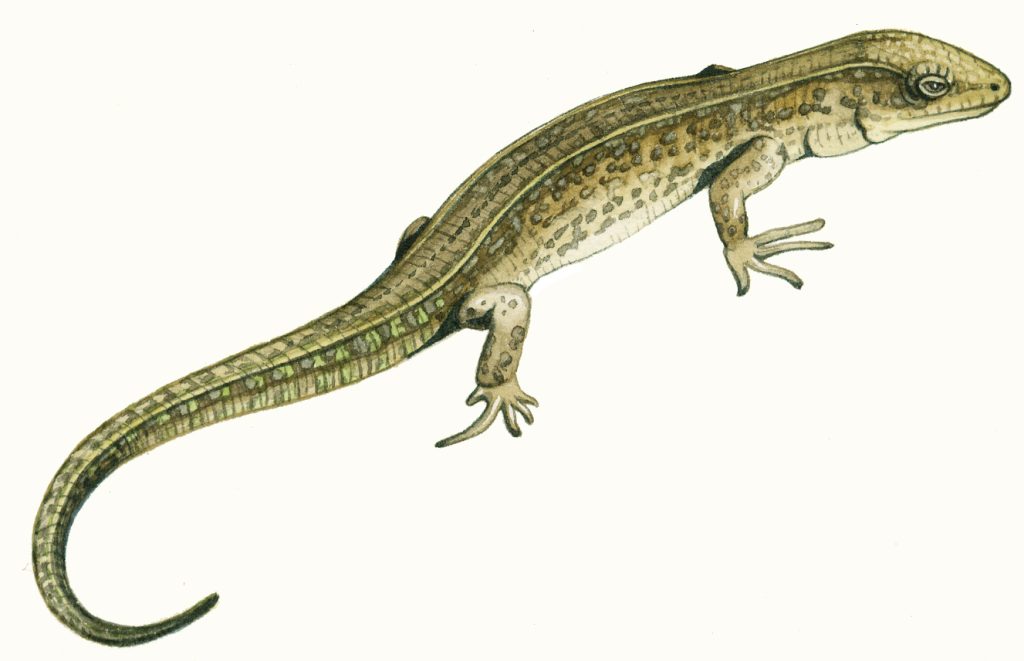

Reptiles: Common Lizard

The Common Lizard is not unusual, although it will scamper away with amazing speed if you spot one and try to get close. Often seen basking on sand or stones in heathland habitats, they’re Britain’s commonest lizard. You may also see them in grassland, and visit gardens too. They’re the only reptile native to Ireland.

As their latin name Zootoca vivipara suggests, they give birth to live young. Well, this isn’t strictly true. They incubate their eggs internally, “giving birth” in late spring.

A female is pictured here. They have highly varied markings, mostly greys and browns. The yellow lateral stripes are a common feature. Males have yellow or orange undersides, while those of the females are paler and cream-coloured. For more on Common lizards, check out my blog on British lizards.

Here’s another illustration of the Common lizard, done for the Bumper Book of Nature by Stephen Moss.

Reptile: Adder

There is also an Adder Vipera berus lurking in this illustration. Famed as our only venomous snake, Adder are far more likely to slither off than to attack a human. Adder bites are unusual, and though painful, are rarely fatal. Like the Common lizard, adders incubate their eggs internally, “giving birth” to a batch of little snakes. Adults emerge in March, and have normally taken to hibernation by October.

Adders can be identified by the dark zig-zag along their backs. They bask in grassland and heathland, and also favour wooded areas. Their venom immobilizes their prey; small mammals, lizards, invertebrates, and ground-nesting chicks. For more on Britain’s snake species, click here.

You can also see the White-tailed bumble bee on a Carline thistle, Yarrow, Stinking iris, Speedwell, and Kidney vetch in this snippet.

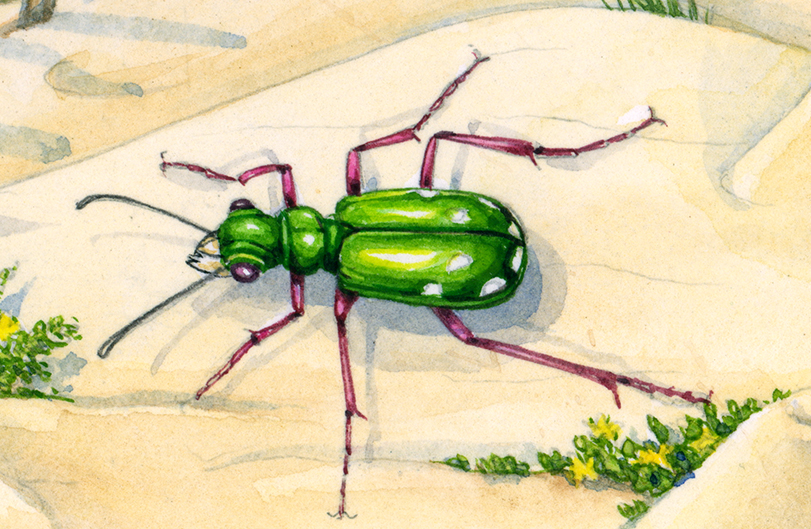

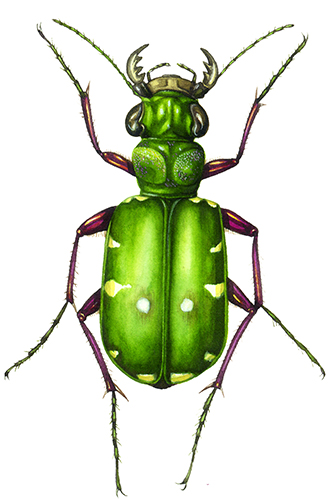

Insects: Green Tiger Beetle

The Tiger beetle is one of my favourite beetles. It’s the ferocity of character, coupled with the dazzling, metallic green sheen on their wing cases (or elytra). The species illustrated here is the commonest in the UK, the Green tiger beetle Cicindela campestris. The fact that it has bronze or purple legs makes its’ appearance even more magnificent.

It’s one of our fastest insects, and ambushes prey at alarming speed. It eats other invertebrates which it seizes with mandibles. Tiger beetles are built for speed with their long legs and strong jaws. You may see them on bare patches of earth, or sand. It’s mostly been hot and dry when I’ve spotted them out hunting. The plant growing along the sand is Biting stonewort.

The larva are predators too. They live in burrows in the sand, where they over-winter, and seize on passing prey.

Insects: Sand and Digger Wasps

I completely love these two solitary wasps, and want to do them justice with a lager and more detailed illustration some day. They are female Red Banded sand wasp Ammophila sabulosa and Sand Tailed Digger wasp Cerceris arenaria, both found in dune habitats.

The Red banded sand wasp (on the left) will dig her nest, then provision it. If (as pictured here) she finds a large caterpillar, there may only be one in the nest cell. Five to eight smaller caterpillars have been found in other nest cells. The caterpillar is brought to the nest on foot as it can be up to 10 times her body weight. Having laid one egg on the caterpillar, she deposits the paralysed food-store into the nest cell and plugs up the entrance so neatly that it’s impossible for us to spot. The whole process takes about 9 hours, and she will lay and provision 10 nests a year.

The Sand tailed Digger wasp is larger, and looks similar to the Bee wolf Philanthus triangulum. Unlike the other wasp, the Digger preys on weevil species, catching them and bringing them to the nest. Her nest is not a solitary cell, but an underground network of cells radiating from a central burrow. They’re about 25cm deep in the soil, and each cell contains one larva and 3 to 15 weevils. I’m indebted to the excellent Nature Spot for this information.

Sand Dunes Management: Depicting Succession

This was the hardest bit of the commission. I want to show how sand dunes slowly become more stable, thanks to the network of roots grown by pioneer species such as Couch grass, Lyme grass, and Marram. These cling onto the sand, making it less likely to erode. For more on Marram grass, check out Karen Netto Andrew’s guest blog.

These early stages of dune development are prone to collapse, known as blowouts. These needed to be incorporated into the illustration too. They look like craters of sand, often in the midst of more vegetated areas of dune.

Marram grass Ammophila arenaria

Once the dunes are less vulnerable to the wind and winter storms, more vegetation can grow which in turn allows a further assortment of species to colonise the dunes. These secondary species include Evening primrose, Stinking iris, Sea bindweed, Restharrow. Then shrubs such as Bramble and Sea-buckthorn can become established, along with plants like Sea carrot, Sea holly, and Sea rocket. For more on these coastal plants check out my blogs on salt tolerant plants, and costal flowers illustrated for the FSC identification chart.

Sea bindweed Calystegia soldanella

Sea Buckthorn Hippophae rhamnoides

This growth starts on the leeward side, away from the wind, which is easy enough to show. It’s the thickening of the vegetative mat that’s a challenge, showing how the plants become closer packed, and how the species change with the establishment of the dunes. Luckily, flowering plants follow the grasses, so I can use colour to show the succession.

Sand dune succession showing growth only on leeward sides, and a blow out

I had to do some swift learning of basic geography here, and am indebted to the concise and useful overview provided by Liverpool Hope University.

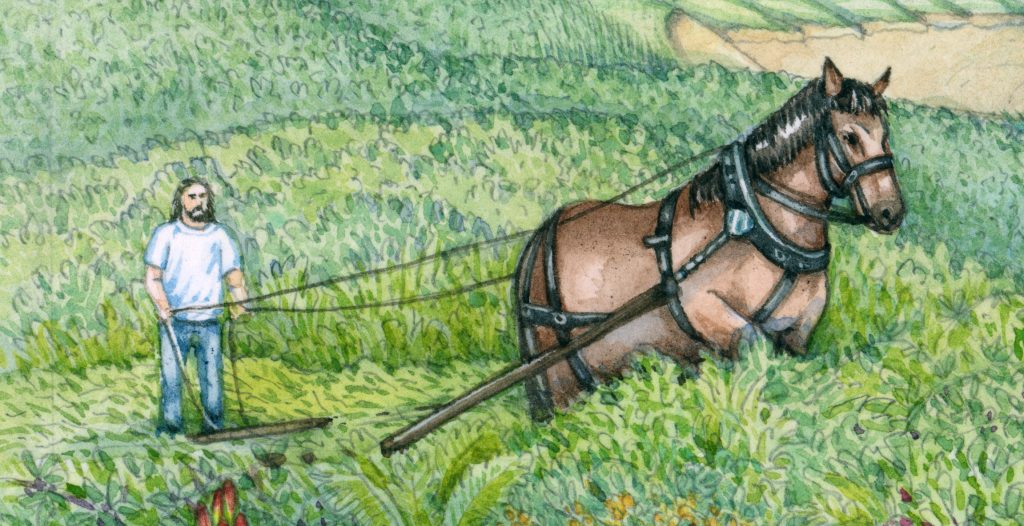

Sand Dunes Management: Suppressing bracken with Rollers

If left un-managed, Bracken Pteridium aquilinum can take over. One of the methods Bantham estate is using to control this plant is horse-drawn rollers. This is the third year using this technique, and it’s not only effective, but also picturesque. Rollers are more effective than cutting the bracken, which allows it to grow back and may even promote growth.

The rollers crush and bruise the stems of the bracken, damage from which the plants cannot recover. Thinner areas of bracken mean other plants have a less densely vegetated habitat in which to compete. For more on this management scheme, please look at the Southhams Today article.

Conclusion

I was planning on putting all the details in this illustration into one blog, but on reflection I’ll pause here, and discuss the butterflies pictured in my next blog. If you’d like to know more about the coastal meadows further inland at Bentham (pictured below), please check out my earlier blog.

Bentham Hay Meadow

You may also be interested to know that although the Coastal meadows illustration has been sold, the original Bentham Sand dunes illustration is still available to buy. It’s about 65 x 40 cm, and costs £ 275 unframed. Please email me on info@lizzieharper.co.uk if you’re interested.