Researching a wildflower

Researching a wildflower involves gathering information on the anatomy, distinguishing characteristics, family, and appearance of a plant. The first stage is to know about the plant you are illustrating. Feel free to use the English name, but do all research using the Latin or scientific name. This avoids confusion as some plants are called different names depending on where you are, even within countries. For more on scientific nomenclature, check out my earlier blogs, What’s in a name part 1 and part 2.

Researching a wildflower: Botany

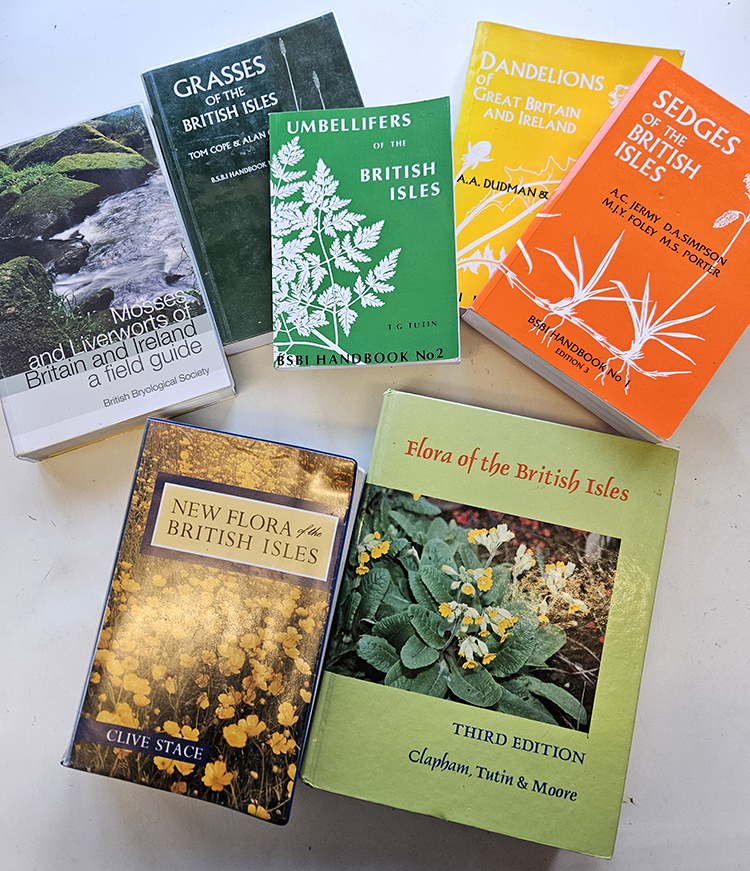

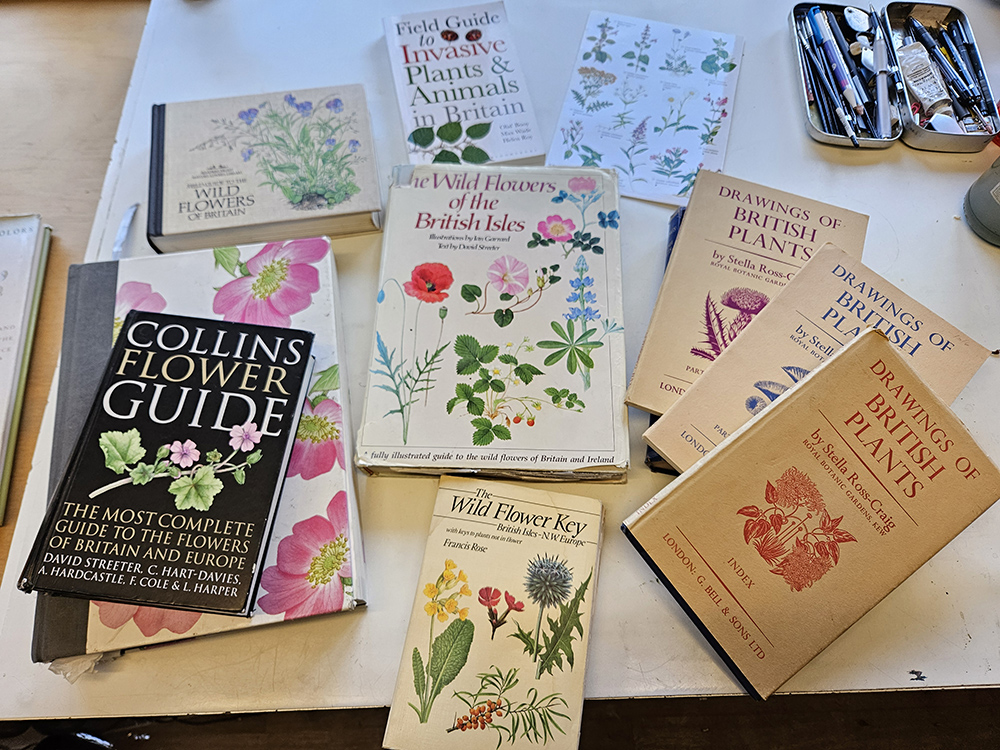

Most of the flowers I illustrate are UK species. This allows me to consult the same reference books. I start by looking up botanical descriptions of the species in two books on British wild plants. These are Flora of the British Isles by Clapham, Tutin and Moore; and New Flora of the British Isles by Stace. I am also building up a collection of BSBI handbooks, all are excellent and help untangle tricky families of wildflowers. I only have 4 but there are 24 titles available. Be aware that if you are researching grasses or bryophytes you will need other identification bibles. For grasses this is Grasses of the British Isles by Cope and Gray (a BSBI Handbook) and Grasses by Hubbard. Mosses need Mosses & Liverworts of Britain and Ireland by the BBS and Atherton.

Books referred to to understand the botany of a species

Navigating Botany reference books

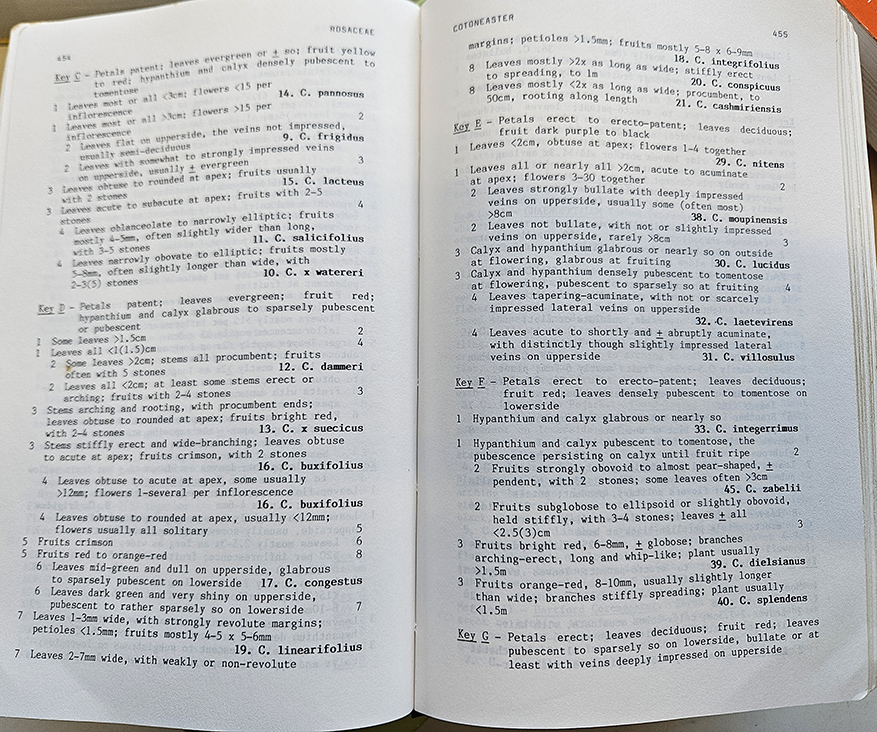

Many of these books are pretty academic and you need a good grasp of basic botanical terminology before they make much sense. Luckily they have glossaries in the back, and with time you get used to their somewhat dry presentation and will learn enough botanical terms for the text to make more sense. You will come across sentences which seemingly contradict themselves such as , “[stems] glabrous, or sparsely pubescent leaves….deeply lobed to…entire; phyllaries…ususaly glabrous to pubescent” (Stace p. 619) but over time you realise this just covers the enormous variation between individual plants of one species. Always remember this. Just as every human being is an individual member of one species, so too are plants individuals within the same species.

Page on Cotoneasters from New Flora of the British Isles by Stace, one of my botany bibles

Books which have helped me learn my botany and which I often refer to are Understanding the Flowering Plants: A practical guide for botanical illustrations by Anne Bebbington. This is massively helpful in terms of explaining illustration techniques and some of the finer points of botany and nomenclature. I also love The Cambridge Glossary of Botanical Terms by Hickey and King and Common Families of Flowering Plants by Hickey & King, again because of the illustrated explanations of botanical terms.

Researching a wildflower: Get the plant to draw!

By far the easiest way to correctly draw a plant is to draw it from life. You can examine it, take it apart, put it under the microscope, and compare it to other individuals of the same species. Colour matching is easy. You can choose a plant that shows the species-specific traits most clearly. I have a mental map of the area where I live and know where to go to find Meadow saxifrage, Petisites, the best Hawthorn berries, Moschatel, Brooklime, and any number of other common and less common wildflowers. Never dig a wildflower up by the roots, or if you have to then replant it as soon as possible, in the same place. Always ask the landowner before picking a flower. Extend the flower’s life by keeping it in a sealed and inflated plastic bag, sprinkled with water and kept in the fridge. Plunge a cut flower into water as soon as you can, after cutting a cm off the stalk base.

Painting holly Ilex aquifolium from numerous specimens

Researching a wildflower: Existing flower guides: Favourites

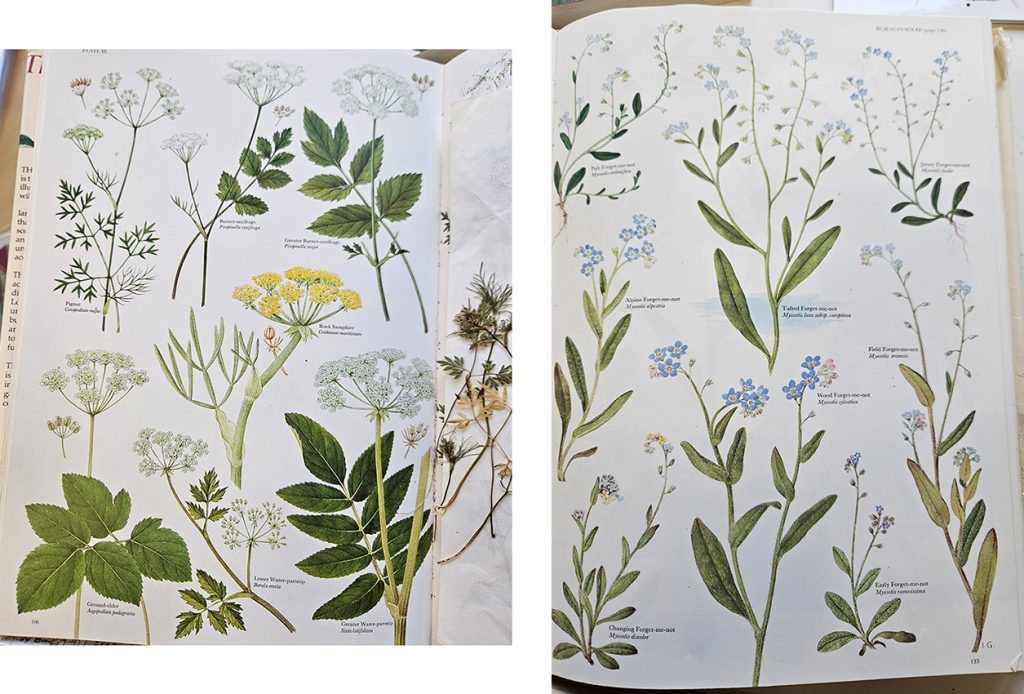

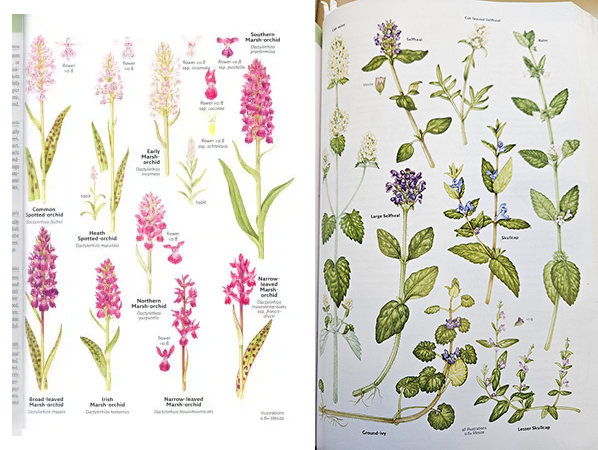

I use lots of Flower guides for reference. These have images which are helpful, and written descriptions which I cross-check with information in the other botany books. I always look at The Wild Flowers of the British Isles by Garrard and Streeter. The illustrations are extremely good for the feel of the plant and colour reference, and although the book is out of print you can get copies secondhand.

Pages from The Wild Flowers of the British Isles along with some dried Pignut leaves slipped in between the pages.

Another book I always check is Collins British Wild Flower Guide by David Streeter. This can be an uncomfortable experience as I did a quarter of the plates, and live in fear of seeing illustrations that I got terribly wrong. I’ve been ok thus far. I press leaves from actual plants in the pages of Garrard and Collins because the books are large format meaning the pressed leaves don’t fall out all the time. In the Collins guide, I find the illustrations by Christina Hart-Davies incredibly useful and clear. I’m very lucky to count her as a friend, and if I am stuck for good reference I can drop her an email and she sends over scans from her sketchbooks.

Collins British Wild Flower Guide a page on the left by Chris Hart-Davies, one on the right by yours truly

Researching a wildflower: Existing flower guides: Others

Other useful illustrated guides include the fold out charts by Field Studies Council (many of which I’ve illustrated, so again, this can feel a bit strange). Readers Digest guide to wild flowers is hit and miss but can have information and details in it that isn’t included elsewhere. The Wild Flower Key by Francis Rose is excellent although in my old edition the illustrations are reproduced rather small and a little blurry.

I should also mention Keble Martin. His work is glorious in both knowledge and composition, but was reproduced in 1965 when image reproduction was not strong and the original plates have long since been dispersed. Someone once told me they saw a Keble Martin original and the lines were crisp and colours perfect, which is heart-breaking. In my Concise British Flora the illustrations are a little brown and blurred.

Although correct in all aspects, I have never got on with the illustrations of Marjorie Blamey which are reproduced in many different guides to UK flora. They are not quite crisp enough to work from, but using them for identification seems to work fine. The copy I have sees them alongside the work of Fitter and Fitter in Collins Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland. Also worth a mention is David Sutton’s Green Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Europe with illustrations by Emberson.

Assortment of illustrated flower guides that I use for reference.

The best illustrated UK Flower guide is…

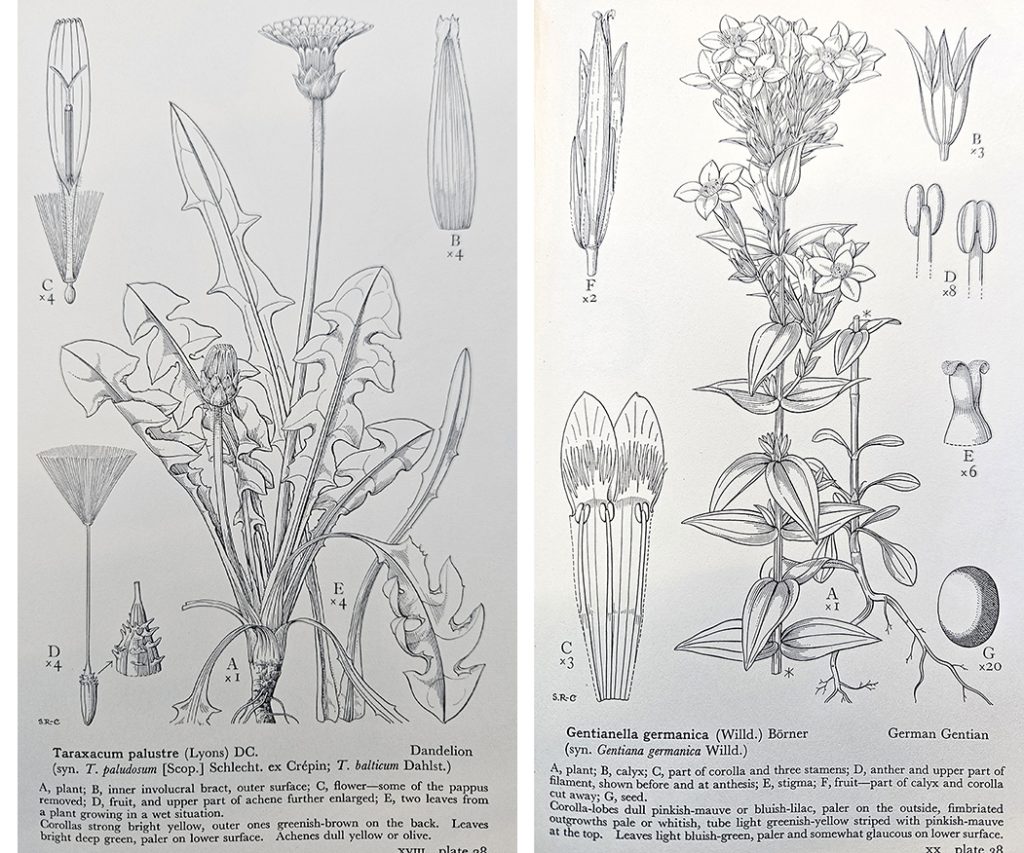

However, the most important reference that I have by far is a complete set of Drawings of British Plants by Stella Ross-Craig. These are pen and ink drawings of most of the UK’s wildflowers, completed across her lifetime. (Not all trees are featured and there are no grasses, rushes and sedges). She produced them in 31 separate parts, family by family. Each plant gets an A5+ size plate to itself. Some of the parts are paperback, some are bound together in blue. The purchase of an index was a great moment for me, as was the day I finally completed my set. Yes, feel free to be jealous.

Time after time she captures the precise feel of a plant’s growth habit. her attention to detail is exacting. The close ups are pertinent and I am an absolute disciple of her work. Interestingly, I often recognize her work in paintings by other illustrators, and I’m sure the same can be said for my pictures. If you can’t get your hands on the actual living specimen, get your hands on Stella Ross-Craig instead. I’m not alone in my passion, as this blog by the National Botanic Garden of Wales shows.

Two plates from Drawings of British Plants by Stella Ross-Craig

Using old illustrations

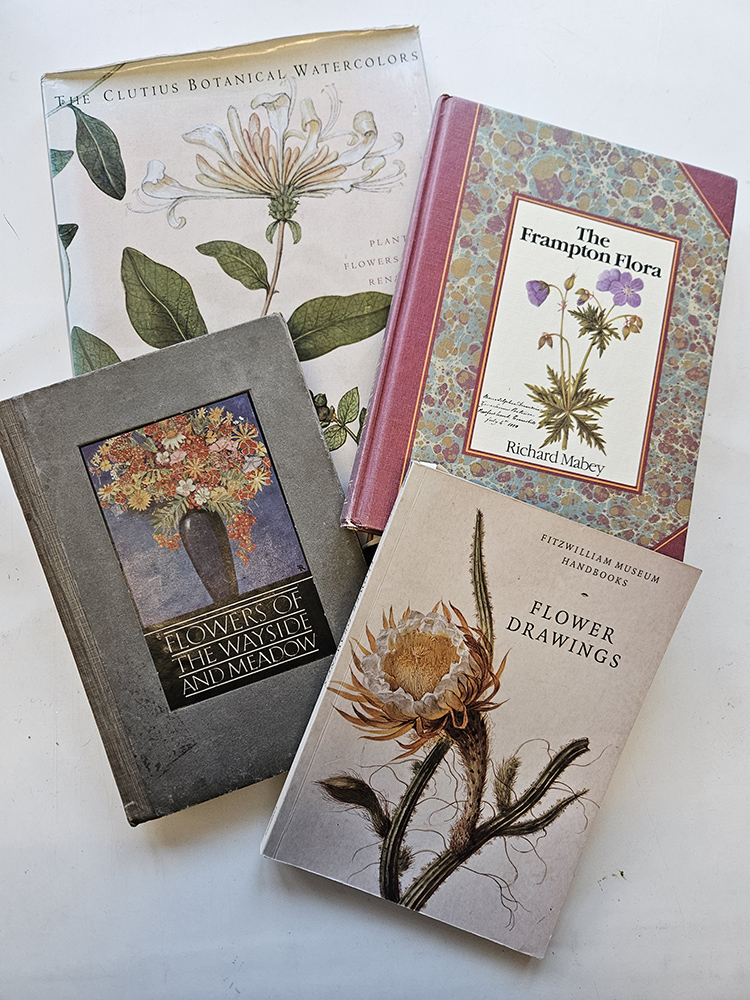

Along with recent books, it is worth looking up old (and in some cases centuries old) illustrations of plants in herbals and manuscripts. Many have been reproduced as coffee table books, but they are a prominent part of my reference library. Titles include the Clutius Botanical Watercolours by Claudia Swan, The Frampton Flora by Richard Mabey, various compilations of old botanical illustration plates, and Flowers of the Wayside and Meadow by J Lloyd Williams. Illuminated manuscripts, books of days, and psalters often have floral edges which are often ridiculously accurate.

Some older reference books

My reference Library

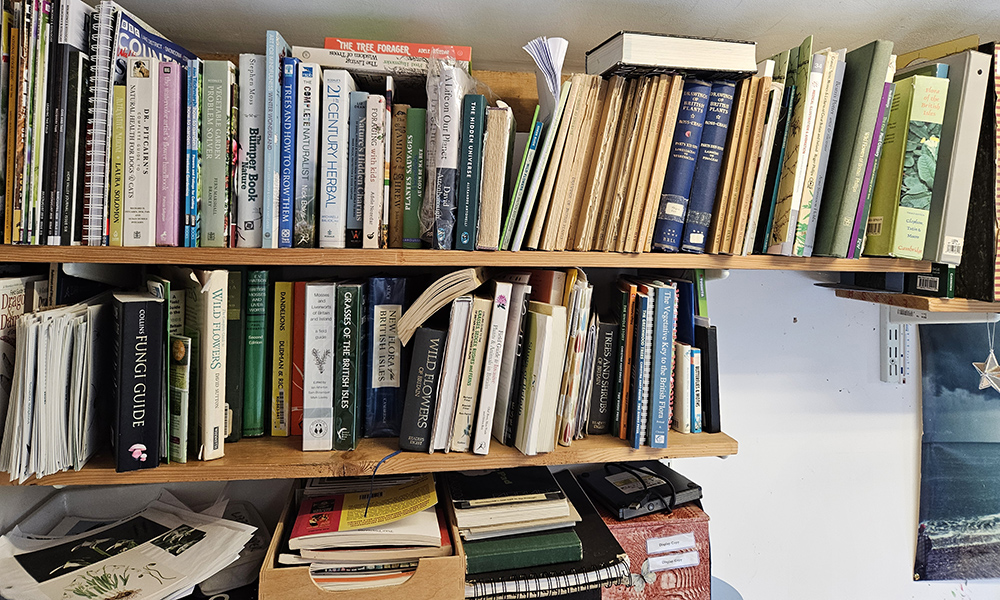

All these reference books take up space, and that’s only the plants! My bookshelves in the studio have half of the top shelf full of my published work and the other space crammed with reference books, sketchbooks, and notebooks full of notes taken from online and in person courses I’ve attended. Things like ellipse guides, greetings cards, and old CDROMS of work also jostle for space.

My studio bookshelves. Horribly chaotic.

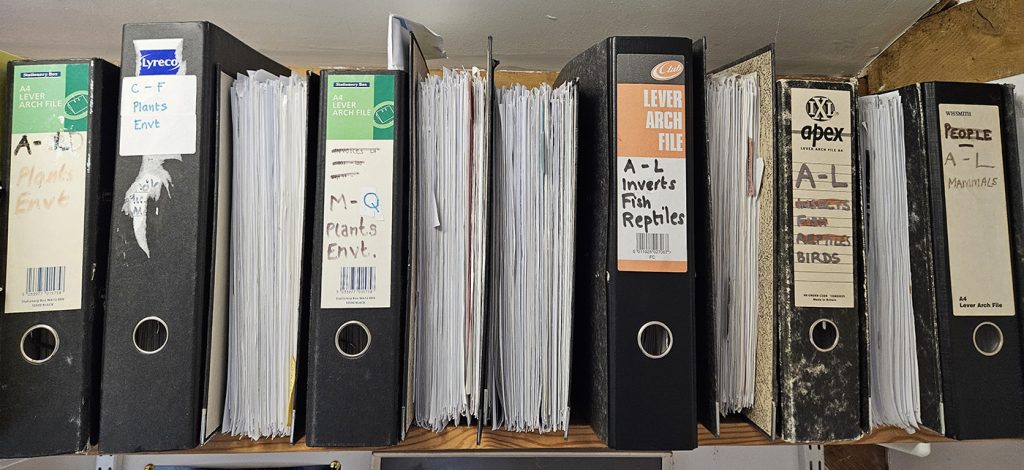

I also keep my printed-out photos of visual reference (from my own archives and online sites). I process and keep them in an ever-expanding set of alphabetised folders.

My A – Z visual reference files

Each time a new species needs drawing, I consult these folders along with my library of reference books and online resources. If it’s a new species, it’ll get a new sheet of A4, neatly labelled and popped into the right ring binder once the plant is painted.

Examples of my pages of reference

Online reference

There are a great many online botany sites, some more useful than others. As part of my research I make my way through a list of about 20, gathering images and taking written notes. A few of the best are Plant illustrations, Kew’s Plants of the World, Naturespot, and Wild flower finder.

Using my own reference

I can’t remember what plants I have illustrated, taken photos of, or drawn in my sketchbooks. Every time I have a new job I’ll quickly flip through my sketchbooks, done between jobs and invaluable for reference. For more on why these are so helpful check out my blog.

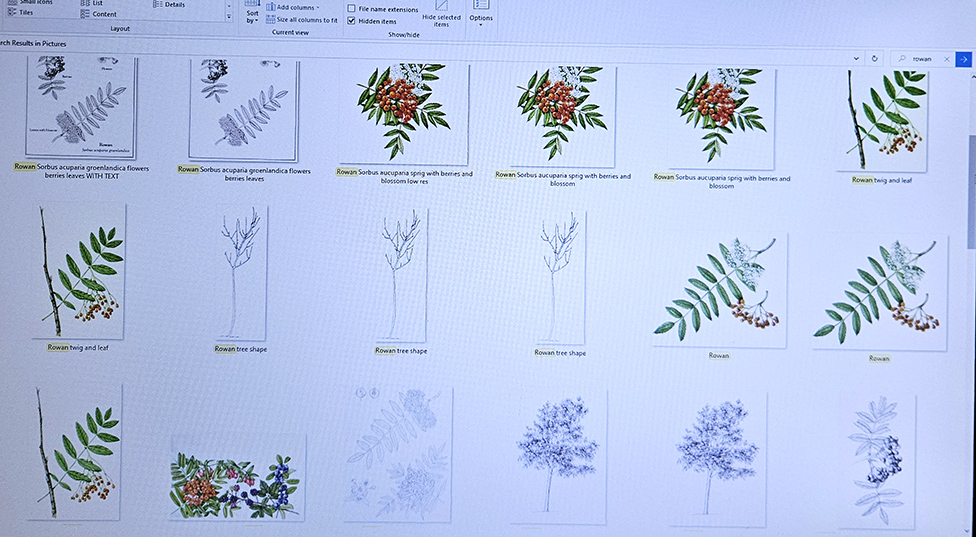

Seeing if I have already illustrated it is easier. I just search my picture files. So long as I’ve not mis spelt the name or got a hyphen in the wrong place, up come thumbnails of that plant.

Own illustrations: Image search for “Rowan”

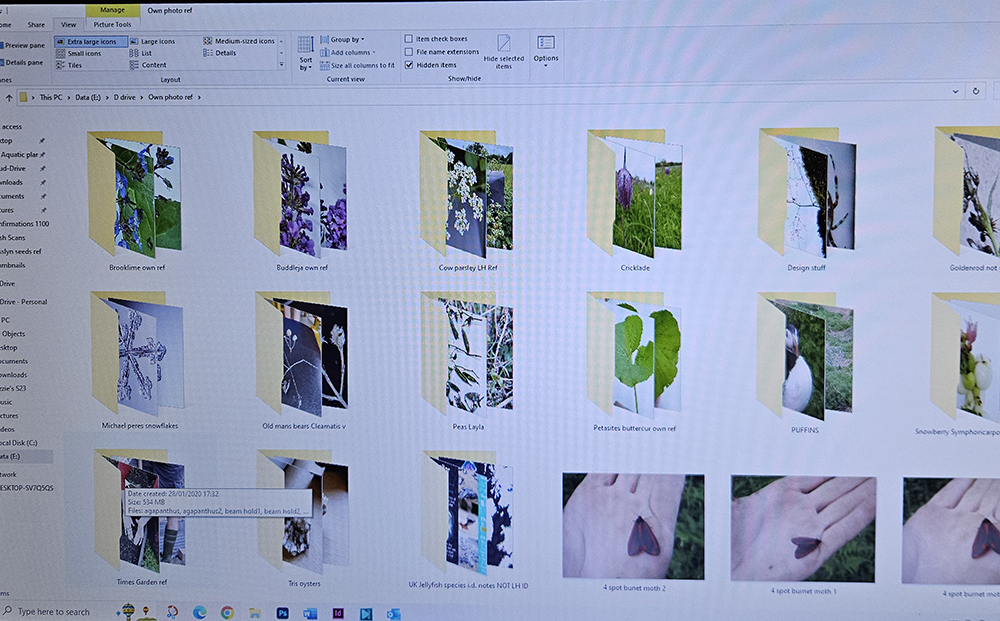

I do the same for my photo archive. So long as each photo is named correctly, I can get my hands on my own copyright free imagery within seconds. As long as I took a photo of the plant when it was growing in profusion under the studio window. Which, irritatingly, I do not always remember to do!

Some of my own photo reference files

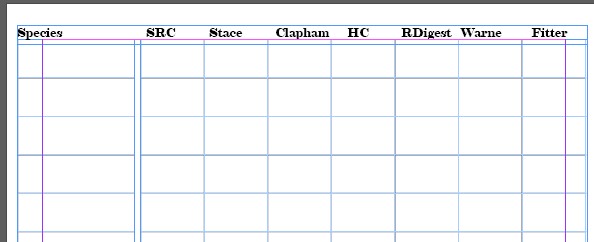

How to collate Reference

I cross-reference written descriptions in flower guides with my botany books to pinpoint the distinguishing characteristics of a species. Sometimes the identification bibles disagree, which can be stressful. To speed up reference gathering, I have a research template which lists my main reference books. I use this to put down the right page number for each new species I’m working on.

Blank research sheet

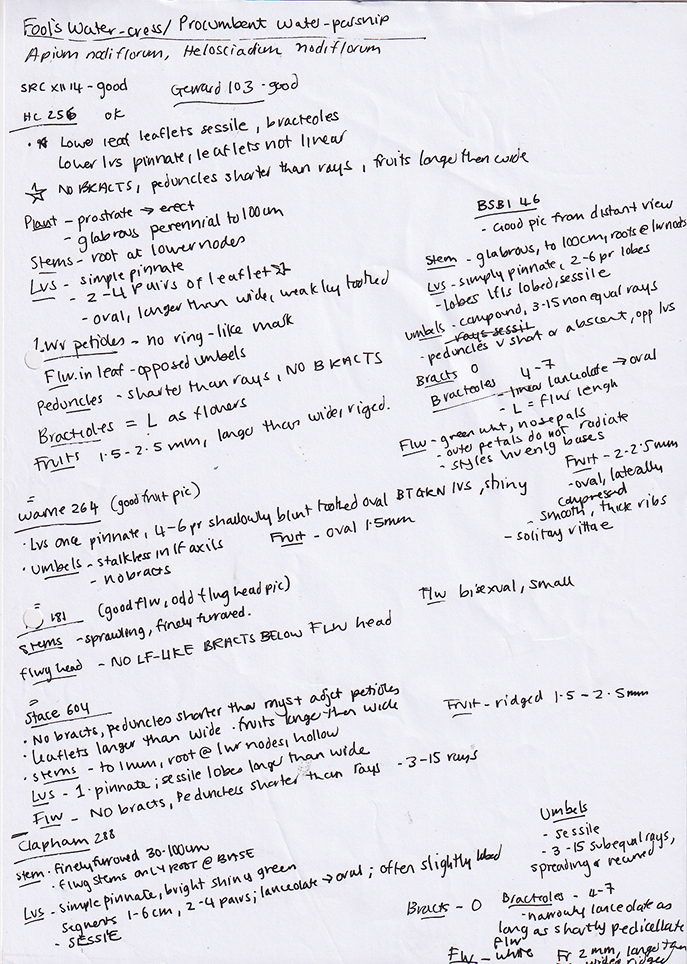

I go through each title taking written notes, then add notes from my online sources. I also collate folders of images found on the internet and print these off. It is vital not to simply copy someone’s photo or illustration as this is copyright infringement, so working from a variety of visual references is really important,

Page of my written notes on the Fool-s water-cress

Collating reference: Examples

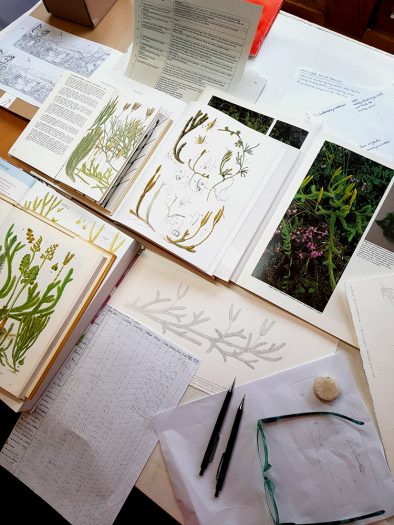

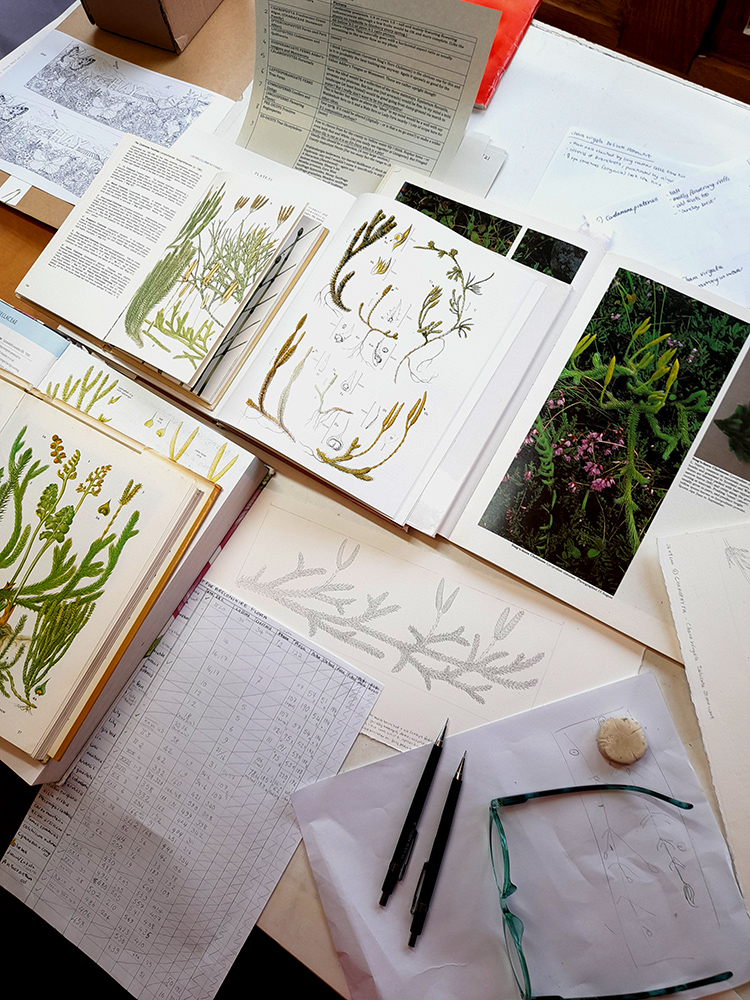

This photo shows how all of it looks as I work on a pencil rough. Sheets of notes, open books, printed pages of text and images. In this example I was working on the Stags horn clubmoss Lycopodium clavatum. The main drawback is that the desk is often so crowded that it can be hard to find a space to draw in!

Working with reference on Club moss illustration

Here is the finished illustration which will features in the Brecknockshire Flora. It was not only a rare plant, but also tricky to correctly identify and was illustrated out of its growing season. There was no way I could have got my hands on the plant. If only….

Stags horn clubmoss Lycopodium clavatum

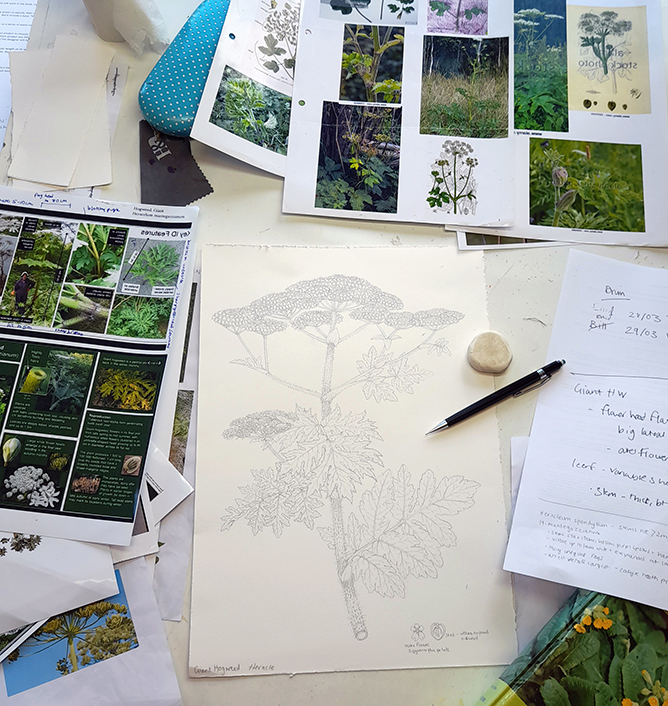

Similarly, the Giant Hogweed needed illustrating out of season. Pages of notes and illustrations followed. Hogweed is a member of the Umbellifer or Apiaceae family, and although not a hard one to identify, it’s important to get its characteristics right as it is not only a pernicious invasive weed, but also has sap that can be toxic if exposed to sunshine. It needs to be instantly recognizable.

Giant hogweed pencil rough and reference

Below is the illustration. The blotches on the stem are particularly important for identification. So too are the differences in leaf shape and the plants’ prodigious size!

Giant Hogweed Heracleum mantegazzianum

More on reference

For more information on how to work from photo reference click the link to my blog. There are different challenges if you are drawing animals. Please check out my getting reference for animal illustrations blog. Below is a film of me talking through this research process. For another opinion of good Wildflower guides, have a look at the Countryfile guide to UK Wildflower guides and theBSBI Guide to Wildflower guides for beginners.

Me talking through the research process as I draw the False Oat-grass Arrhenatherium elatius

Well…I don’t think that it is possible to visualise the scientific descriptions of plants. Even if you are super familiar with each term let’s say for each and every part of each and every plant, and even if you have the drawing skill to put them together according to the description I don’t think that you will end up with something that looks like the actual plant without a speciment or a photo or an other illustration as a reference.

Totally agree. SO you unite the visual imagery with the botanical description. Noone can tell what a plant looks like from words alone, yo’rue right x

How does the choice of location impact the research process when studying wildflowers? Greeting : Telkom University

Hello

When doing research, it’s good idea to choose a representative example of a wildflower, rather than one that’s growing in shaded conditions or in soils which may make them stunted.

This is so helpful Lizzie, thank you! xx

My pleasure!