What’s in a name? part 1

Natural history illustrators are asked to illustrate a wide variety of plants and animals. It’s vital that you draw the correct organism! With so many similar species out there, I can honestly say that I’d be lost if it weren’t for the use of a Latin name. These pinpoint the living thing you’re illustrating.

Using names to classify life

So how does this system of naming work? It’s vital to remember that naming things is a very human trait. We have invented this complicated and detailed format to be able to identify all living things. It’s by no means a perfect solution. Latin names are forever changing as new information on relationships between animals or plants is revealed. Sometimes organisms don’t fit neatly into the named boxes we’ve built for them. Saying that, it’s human-kind’s messy attempt to classify and organise the world around us. Although it’s not perfect, it’s globally used and does the job.

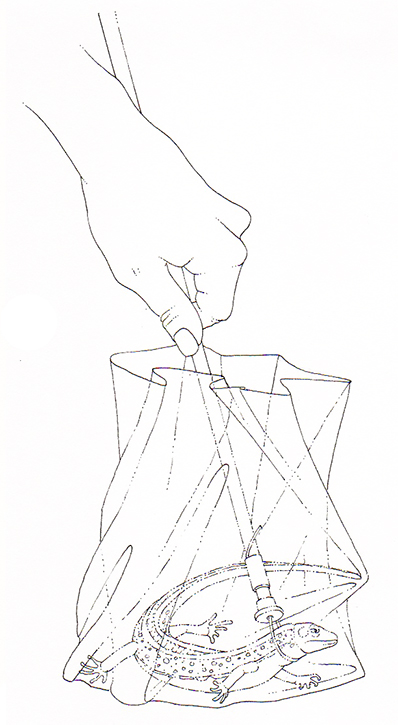

Catching a lizard safely, from “The Complete Naturalist” by Nick Baker

A name explains relationships between organisms

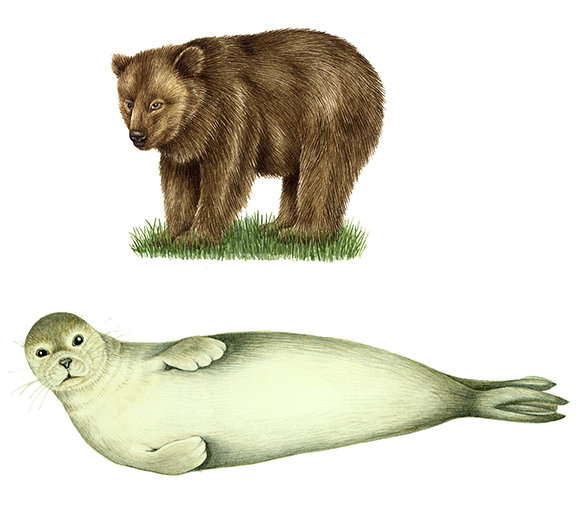

Every living thing which has been identified by scientists has a whole string of Latin names. This system was devised by the scientist Carolus Linnaeus in the 18th century. Each name not only helps pinpoint a particular species, but also gives a vast amount of information about how similar plants and creatures are. It explains evolutionary relationships. This is called the “phylogenetic relationship” and is used to categorise organisms. Sometimes, the close relationship between seemingly different creatures can be surprising.

Seals and Bears share a common ancestor and are quite closely related

Pneumonic to remember the order of names

At high school the Latin system of naming was taught to me as “King Philip Came Over From Germany Singing”. This is a good way to remember the letters K, P, C, F, G, S in order. And what does each letter stand for? K is Kingdom, P is Phylum, C is Class, O is order, F is family, G is genus, and S is species.

K is for Kingdom.

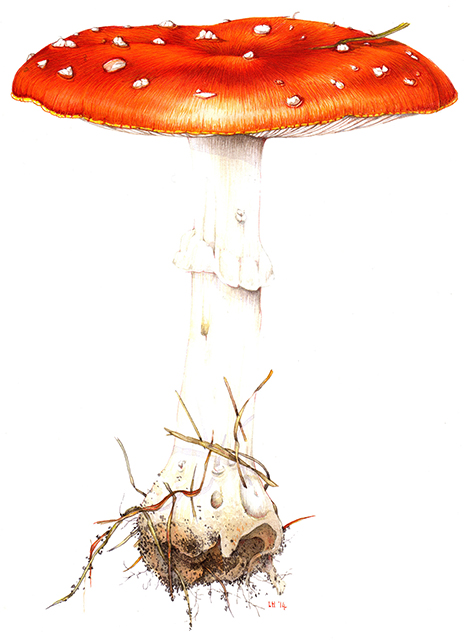

Currently, sources agree that there are six kingdoms of organisms. These are Eubacteria (prokaryotic and unicellular, including Bacteria). Next is Archaebacteria (again prokaryotic unicellular organisms such as Methanogens and Thermophiles). We have Protista (eukaryotic and uni or multicellular). Fungi form another kingdom. Then there’s Animalia (animals). Finally, we have Plantae (plants). Kingdoms are written with a capital letter, but not in italics.

Fungus is one of 6 kingdoms of organism (this one’s the Fly agaric Amanita muscaria)

P stands for Phylum.

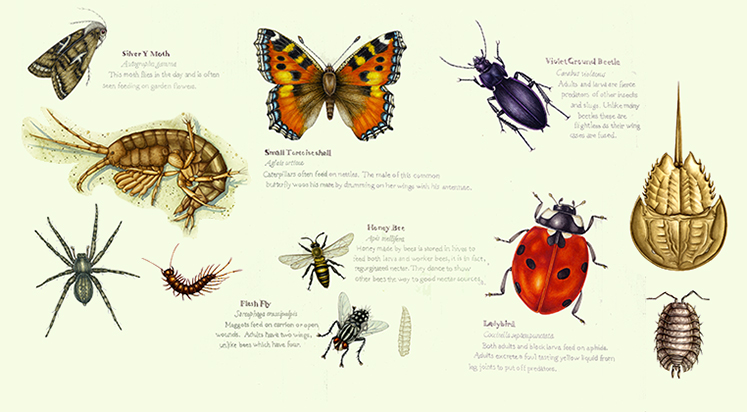

A phylum falls between a Kingdom and a Class and includes broad groups of organisms such as Arthropods (insects, crustaceans and arachnids), or the phylum Chordata into which humans fall. Chordata also includes all vertebrates, so it’s a vast category. Phyla are written with a capital letter, and not italicised.

Some of the vast numbers of animals that are classed as Arthropods

C is for Class.

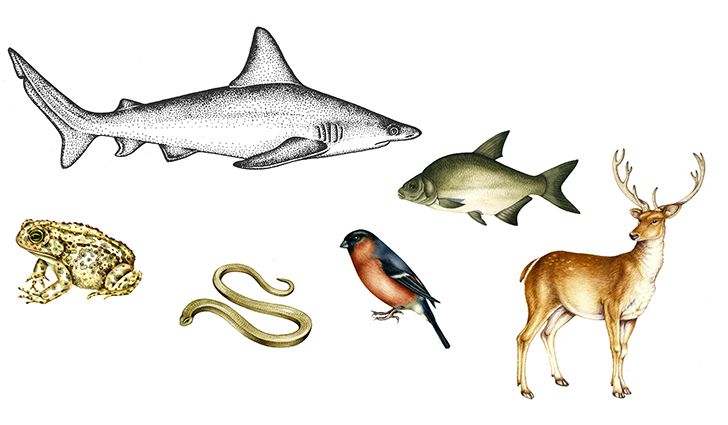

A class is a more closely related group than a phylum, so within the phylum of Chordates you have 7 different classes; jawless fish (Agnatha), fish with cartilage but no bones (Osteichthyes), amphibians (Amphibia), reptiles (Reptilia), birds (Aves) and mammals (Mammalia). Each phylum is subdivided into these different taxanomic groups. Classes bear a capital letter but no italics.

Representatives of all 7 classes of Chordates (excluding the jawless fish, Agnatha)

Interestingly, these days botanists tend to dispense with classes and prefer the use of the looser term, “clade”. This change was heralded in 1998 by the APG or Angiosperm Phylogeny Group which reclassified flowering plants. It’s been tweaked and updated to reflect molecular similarities between species. These have been discovered thanks to the advancement of techniques since the 1990s. We now operate under APGIV (published in 2016).

O stands for order

An order is a grouping of increasingly similar plants or animals. If we look within the class Amphibia we find three orders. These are Anura (frogs and toads), Apoda (caecilian “worms”), and Urodela (salamanders and newts).

Representatives of all three orders of Amphibians

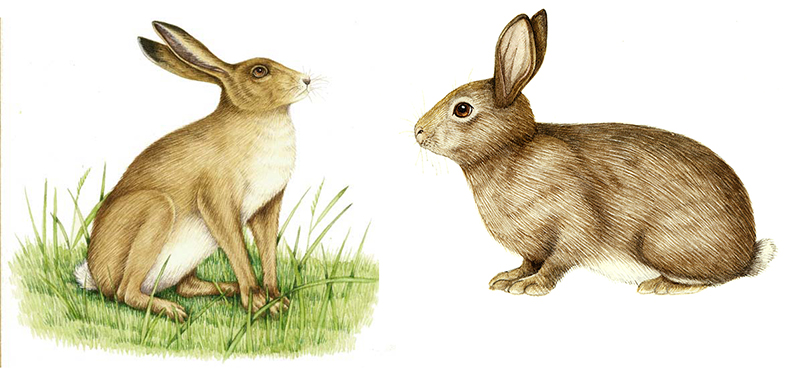

Within the class Mammalia there are many more orders. These include the Monotrema (egg laying mammals) and Carnivora (carnivores including lions, wolves, racoons and bears). Lagomorpha (rabbits and hares) and Chiroptera (bats) are two mroe orders. There are lots of others. These classifications are always shifting and changing as different molecular facts about relationships between species are discovered. Almost every text book will give a slightly different list of Mammalia orders. Orders are written with a capital letter and no italics.

Hares and rabbits are Lagomorphs, one of many oders in the Mammalia class.

F is Family

Family refers to a group of organisms even more closely related to one another, and sharing common attributes. Confusingly (as with the orders of animals and plants where you find sub-orders) you can also find sub-families which slot in between families and genus. Bear with me.

Oaks and beeches are in the same family (Fagaceae) which sits within the order Fagales. With names in botany, it’s quite common to see the –aceae ending when you’re talking about families of plant, and the ending –ales often turns up in order names. Large families can be divided into tribes, or into subfamilies (oaks and some other similar species are in the subfamily Quercoideae) which often bear the –oideae ending.

Beech and Oak are both in the Fagaceae family. Pictured here is the European beech Fagus sylvatica and the English oak Quercus robur

In our example of amphibians, there are 31 families within the order Anura (frogs and toads). It’s at the family level that you start to realise the distinctions between similar animals really do need to be made by biologists; there are over 59 different families of snails! As before, family names bear a capital letter but are not italicised.

From the family name you get increasingly specific; next comes the Genus name and finally the very specific species name. These are always written underlined or in italics, and allow you to confidently pinpoint the precise organism you’re looking at. For more on Genus and species, please look at my Blog on Scientific names: What’s in a name? part 2