Trees: Horse chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum

Trees: Horse chestnut is one of a series of blogs I’m writing on common British trees. You can also see blogs on the Elder, the Yew, the Ash, the Oak, the Holly, the Sycamore, the Rowan, the Hawthorn, the Lime, Scots pine, and the Beech.

The Horse chestnut is easily recognized, with distinctive palmate leaves and an autumnal crop of conkers. It was introduced from Turkey around the 1600s, and is a common tree in parklands and towns, but occurs less often in woodland.

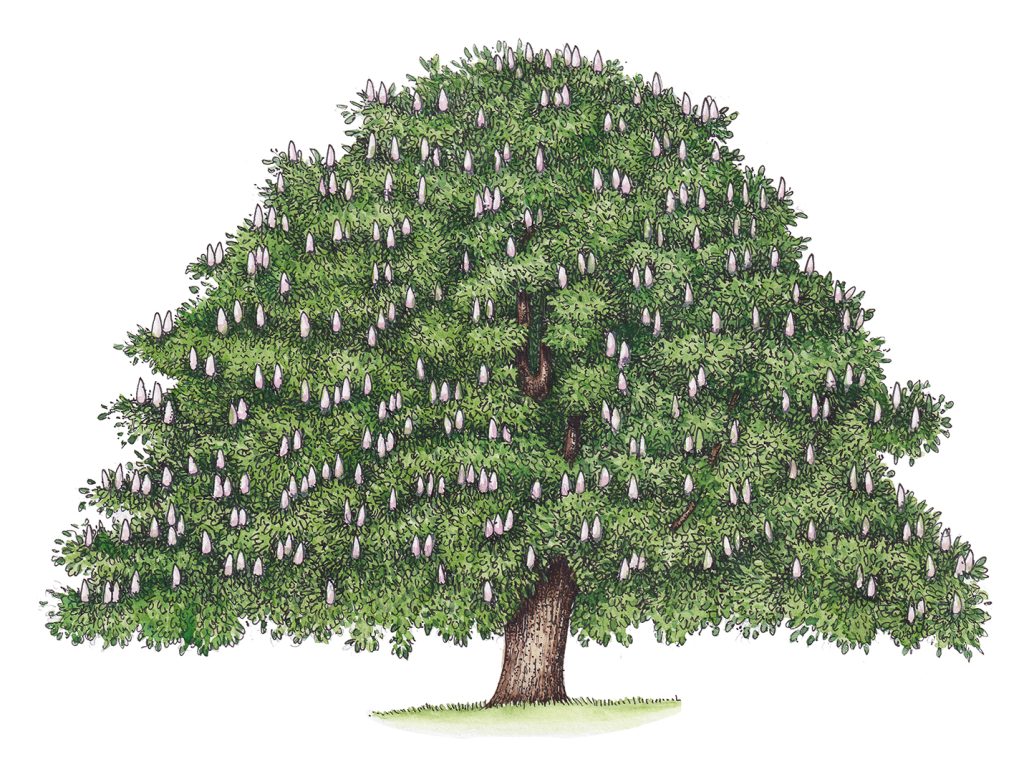

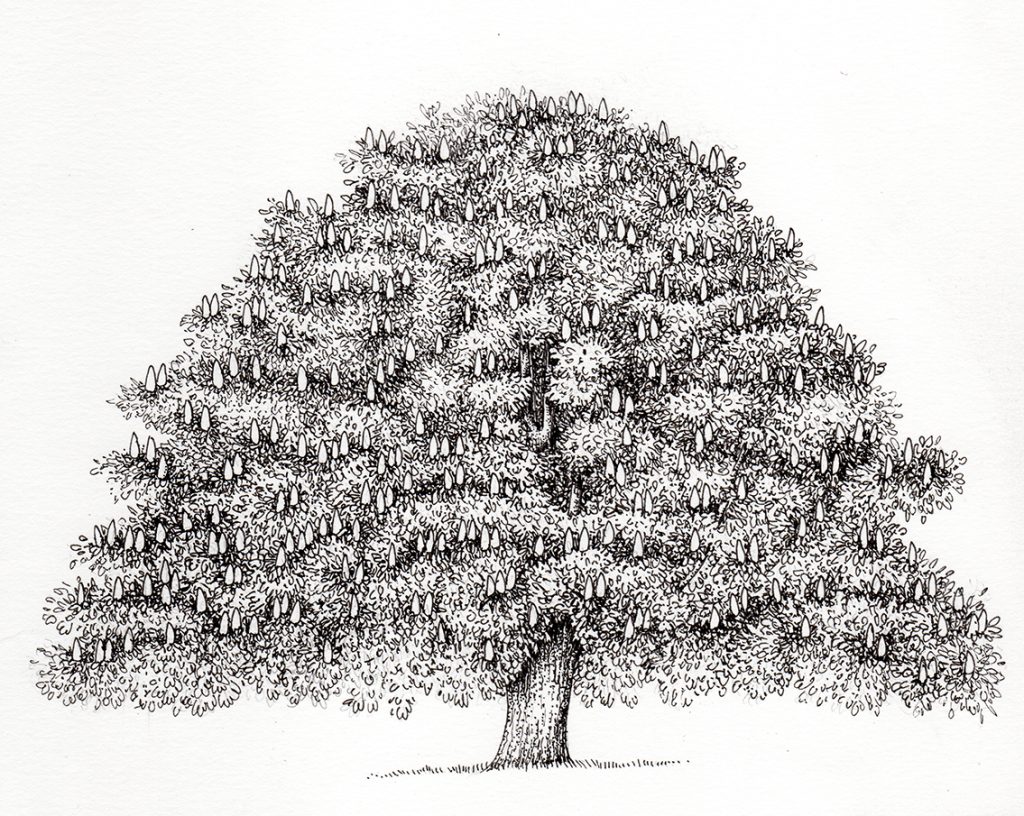

Identification: Tree shape

The tree grows up to 40m tall and has a wide, domed canopy with foliage coming low down the tree. Trees live up to 300 years. It grows fast in most soils, and needs plenty of space.

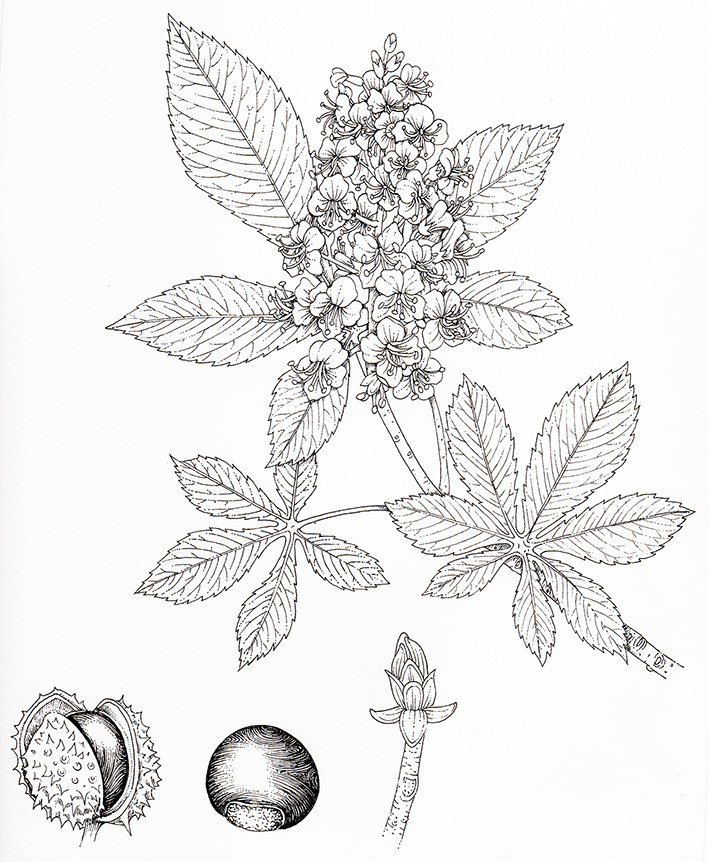

Identification: Leaves

Horse chestnut leaves are palmate, consisting of 5 – 7 sharp-tipped leaflets arranged like the fingers of an outstretched hand. Each leaflet can be 30cm long, making for impressively large leaves.

The leaf margins are toothed, and each leaflet has clear alternate lateral veins. They’re a rich green colour. For more on leaf margins click here. For a blog on compound vs simple leaves click this link, and tips on leaf shape can be found here.

Identification: Flowers

The flowers of the Horse chestnut grow in a clustered tower of up to 50 flowers, known as a panicle. These are sometimes referred to as candles. Branches of the panicle are longer at the base than the top, creating a cone shape. The uppermost flowers are male, those in the middle are both sexes, and the lowest ones are all female.

They have a distinctive shape with bilateral symmetry. Each flower is 9-11mmm long and has 5 fringed white petals, with a yellow patch at the base. Once pollinated, this turns from yellow to dark pink. This may communicate to visiting insects that the flower is no longer worth visiting as it has ceased providing nectar post fertilization.

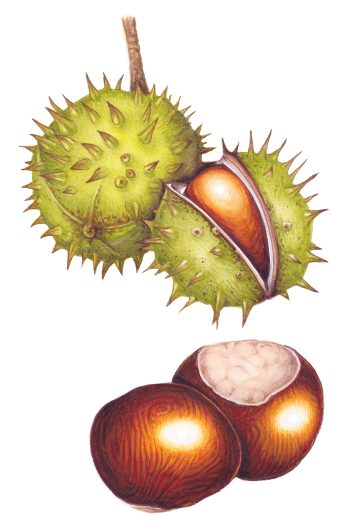

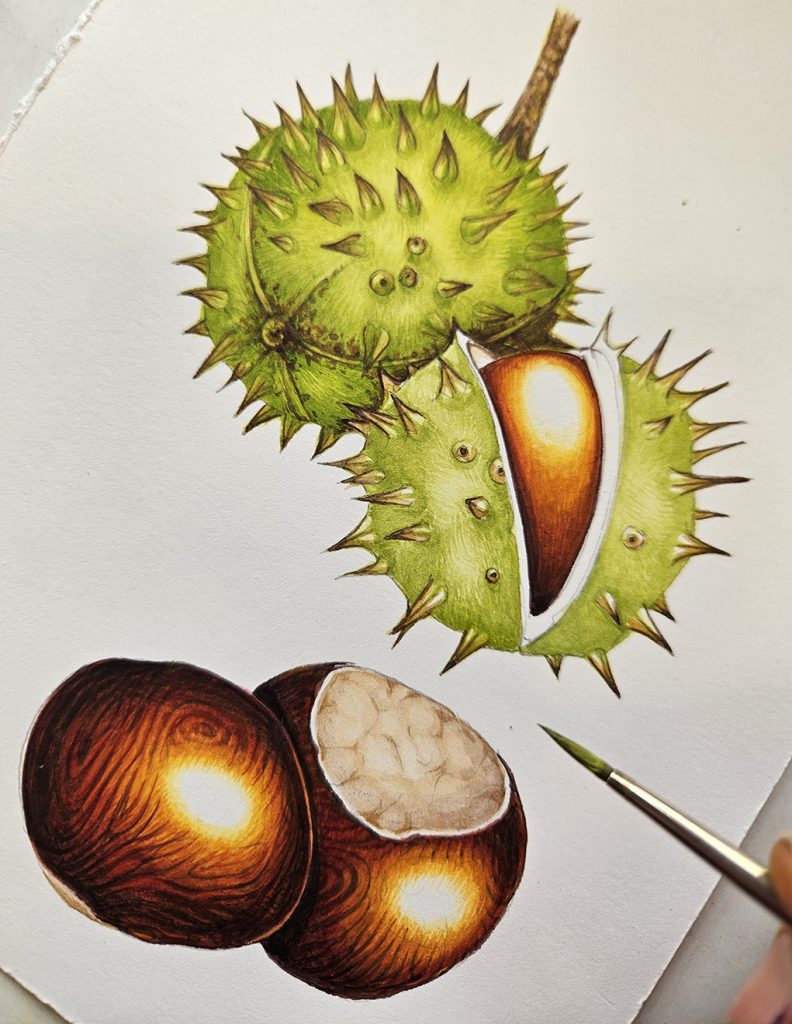

Identification: Fruit

Horse chestnut seeds are known as conkers. Only 5 or so flowers per panicle develop into conkers.

The conker is instantly recognizable. Encased in a pale yellow-green, spiked case; conkers are a shiny mahogany brown. This type of seed is known as a capsule by botanists. (For more on seed types, check out my blog.)

There are 1-3 conkers per fruit, released when the seed case splits three ways at maturity. Each is up to 4cm across, with the entire fruit measuring up to 7cm

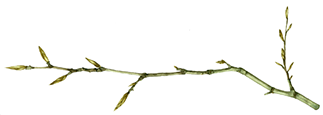

Identification: Bark and buds

The bark is pinkish-grey and thin in young trees, becoming grey-brown and scaly with age.

Buds are distinctive and grow on stout hairless twigs. They are a rich reddish brown, oval, and very sticky. Lateral buds are opposite.

When the leaves shed, they leave a distinctive horseshoe-shaped scar. This could be the source of the tree’s name; although some suggest it relates to the curative flour, made from ground up conkers, that used to be fed to horses.

Similar species

The Indian Horse chestnut, Aesculus indica, native to the Himalayas, is the only similar species. Like the Horse chestnut, it is planted in parks and public spaces.

However, it follows in June rather than April to May and is a less robust tree. Indian Horse chestnut conkers are small, dark brown and wrinkled, and held in smooth green seed cases.

History: Folklore

Because the tree was introduced to the UK comparatively recently, there’s not a great deal of folk lore associated with it.

However, the conkers are threaded onto strings and used to play – wait for it – conkers. The first recorded game occurred in 1848 on the Isle of Wight, although there’s evidence the game was played with other less suitable nuts prior to this.

To play, you take it in turns to whack your opponent’s conker with your own, the aim being to smash your opponent’s conker to bits. Baking, pickling in vinegar, and drying for a year or more are all methods thought to toughen up a prize conker. To this day, kids in the UK play conkers every year (although some well-meaning schools have banned the practice because it’s deemed dangerous).

One foot note is that some think keeping conkers in a room discourages spiders. My studio has an open box of conkers and a plethora of friendly spiders, so I remain unconvinced.

History: Mankind and Horse chestnut wood

The wood of the Horse chestnut is pale and light. It is weak and is mainly used to make children’s toys and for carving. As it’s absorbent, it is also used to make trays for storing fruit, and it was sometimes used to make light weight artificial limbs.

History: Food and Medicine

Conkers were ground up into flour in Victorian times, and used as a coffee substitute during World War 2. The mildly poisonous nature of the fruit, and its limited appeal has made this practice obsolete.

Flower buds can be used as a substitute for hops in beer brewing

Medicinally, conkers were fed to cattle and horses by Turkish soldiers in the 1600s to cure respiratory disorders.

Varicose veins, haemorrhoids, sprains and bruising can all be treated with Horse chestnut creams which thin the blood. This makes it harder for blood to leak from veins and capillaries, and is useful in the treatment of water retention and oedema. Aescin seems to be the active compound at work here, both for animal and human ailments.

Finally, the high levels of saponin made them good for making soap, after crushing and soaking the conkers in boiling water. They are considered useful as moth deterrents by some.

Horse chestnut and Wildlife

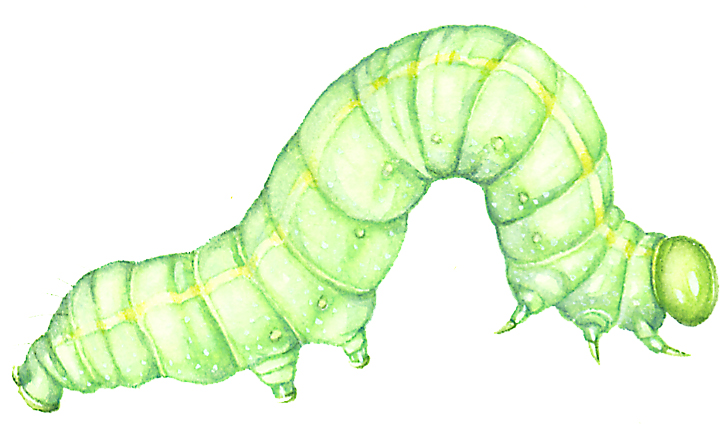

The profusion of flowers provide a welcome treat to pollinating bees in late spring, and the caterpillars of the Triangle moth Trigonodes hyppasia feed on the leaves.

The larva of the Horse chestnut leaf mining moth Cameraria ohridella also feed on the leaves, the caterpillars are part of the diet of birds like the Bluetit.

Threats

Two pests and diseases have taken a firm hold of the Horse chestnut population recently.

The first is the Horse chestnut leaf miner mentioned above. This insect burrows through the leaves, eating as it goes. It can make entire trees look ill with blotched, yellowing leaves. The good news is that there’s little evidence that the caterpillars do any lasting damage, merely altering the appearance of the tree.

The second is Horse chestnut bleeding canker, a more serious threat. This bacterial infection damages the wood and bark, blocking the tubes of the phloem, making it impossible for the tree to carry water and nutrients. This eventually kills the tree.

Signs of the canker include oozing dark patches on the trunk, discolouration of the wood, and chunks of bark peeling away. This canker is becoming more common since it was first noted in the 1970s, and now infects more than 30% of English Horse chestnuts.

Trees also suffer leaf blotching caused by the Guignardia fungus, and are prone to scale insect infestations.

Conclusion

With their beautiful candles of flowers and ornamental stature, Horse chestnuts are handsome trees. Although of limited practical or culinary use, they are vital to parkland and gardens. One can but hope that the threats posed by canker and pests don’t end up reducing the population of these trees too seriously.

Online sources for this blog include websites of the Woodland trust, Trees for life, Totally wild, the Tree guide UK, and NatureSpot. Reference books for this blog include the excellent The Greenwood Trees by Christina Hart-Davies , and the Reader’s Digest The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain (out of print but commonly available second-hand). I also referred to The Tree Forager by Adele Nozedar and The Living Wisdom of Trees by Fred Hageneder.

Wow. Informative Article

Many thanks

Can i get more Information About this?

Hi Morina

What would you like to know? If you were interested in buying any of the artworks in the post please email me on info@lizzieharper.co.uk

Cheers

Nasz najlepszy sposób na udany za kupić prawo jazdy ! Nasz specjalny portal upraszcza drogę do uzyskania prawo jazdy i oferuje porady ekspertów oraz najnowsze informacje na temat tego, jak kupić legalne prawo jazdy w Polsce bez egzaminu.

Oferujemy kompleksowe usługi, które pozwalają uzyskać prawo jazdy z oficjalnym wpisem do rejestru. Niezależnie od kategorii, którą potrzebujesz, zajmiemy się wszystkim – od przygotowania dokumentu po jego rejestrację w urzędowych bazach danych. Nasza procedura jest prosta i w pełni dyskretna, dzięki czemu nie musisz martwić się o żadne komplikacje. Gdzie mozna kupić prawo jazdy z wpisem do rejestru