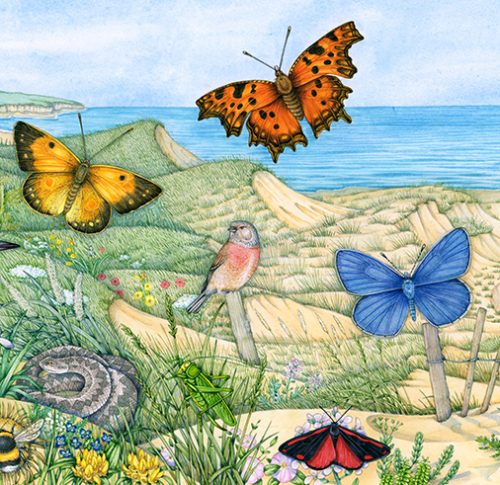

Butterflies of Bentham Sand dunes

Several butterflies are included in the recent landscape illustration completed for South Devon Area of Natural Beauty. This blog will discuss each species, and links to my earlier blog on the wildlife and plants of Bentham bay sand dunes.

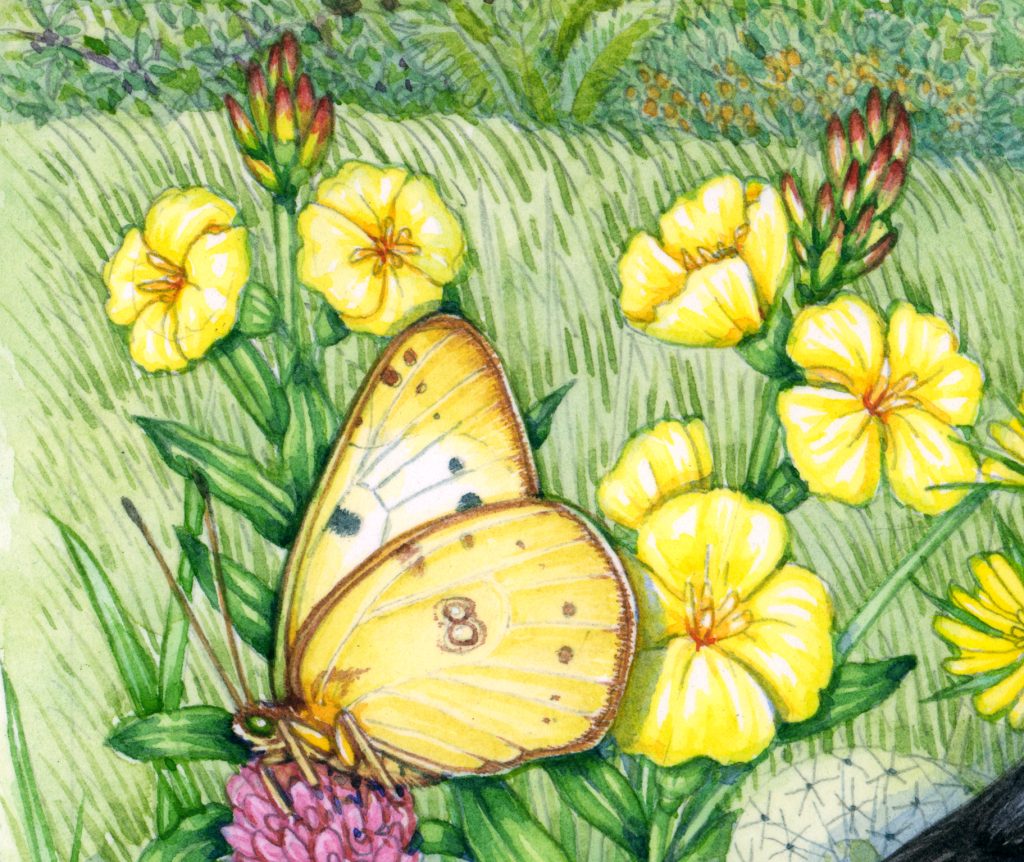

Clouded Yellow

The Clouded Yellow, Colias croceus, travels to Britain every year from southern Europe and Africa. Nine out of ten years, they’re around, but not terribly common. But about once a decade you get a “Clouded yellow year”, when loads of these insects arrive. In fact, so many arrived in 1947 that the military, “saw them approach the coast in the form of a great golden ball, which they thought at first to be a cloud of poison gas drifting over the water” (L. Hugh Newman, quote taken from The Butterflies of Britain and Europe by Lewington and Thomas, a volume I’ll be referring to throughout this blog.)

They’re unable to survive the British winter, but are found all across the UK, feeding on clovers and legumes. In late summer the new generation hatch, and will migrate back across the English channel as autumn approaches.

Female Clouded Yellow

Females and males are both a rich gold, with dark wing margins. In fact, they were once known as the “Saffron butterfly” in the UK, which is entirely understandable.

Both sexes have a pair of orange spots amongst the yellow of their lower wings, and a pair of small, ragged, dark spots on the upper wing. Unlike the males, the females have pale spots in their wing margins.

At rest, they are less striking, showing paler yellow underwings. They rarely flash the brighter top wings when at rest, so can be harder to spot.

Clouded yellow at rest on clover

Possible confusion with other species

Occasional migrants of the Pale and Clouded Yellow butterfly make it to the UK (Colias hyale and Colias alfacariensis). These are tricky to tell apart, and equally difficult to tell from a pale helice form of the Clouded Yellow.

However, the other common yellow butterfly is the Brimstone, Gonepteryx rhamni. Brimstone are a very different, paler and brighter shade of yellow, and almost seem to have a pale glow to them that’s absent in Clouded Yellow. The lack of dark wing margins also makes it really easy to tell the two species apart.

Brimstone butterfly Gonepteryx rhamni

Comma Butterfly

The Comma, Polygonia c-album, is one of my favourite butterflies. It’s instantly recognisable, with its orange and brown colouring, and its ragged wing edges. Both sexes look alike, although the undulating wing margins are more pronounced in the male.

At rest, the underwings resemble a dried out leaf. The little white comma at the centre of the lower wing looks like a tiny hole in an old leaf. The camouflage is remarkable.

Commas have two visually different populations, discovered and researched back in the 1890s by Emma Hutchinson. The earlier population, which is produced from the first of the season’s caterpillars, is known as the Hutchinsoni form. It’s a paler and more golden orange, and behaves rather differently to the browner, deeper orange form produced later in the summer. Unlike the early butterflies, these later ones will be overwintering, so need to focus on feeding and stocking up reserves for their hibernation. They spend this time hidden in woodlands, amongst roots and holes in trees, trusting autumnal leaves to help their camouflage.

In truth, unless I see a Hutchinsoni form alongside the later population, I can’t readily tell them apart. Hopefully, having researched this blog, my skills in this department will improve!

Commas used to feed on hop plants, but have managed to adapt by using the equally nitrogen-rich nettle as a host plant. This has enabled them to survive the decline in hop crops.

In the late 1880s, Commas became incredibly unusual, and many naturalists thought they were gone for good. Perhaps the beginnings of insecticide use on hops around then, and a new procedure of burning hop remnants may have triggered the decline. Wonderfully, now the population is stronger than ever. An increasingly warm climate, and the use of nettles may well be the reason. Either way, it’s a truly welcome development.

Possible confusion with other species

Due to the distinctive ragged wing edges, the Comma is unlikely to be confused with any other British butterflies.

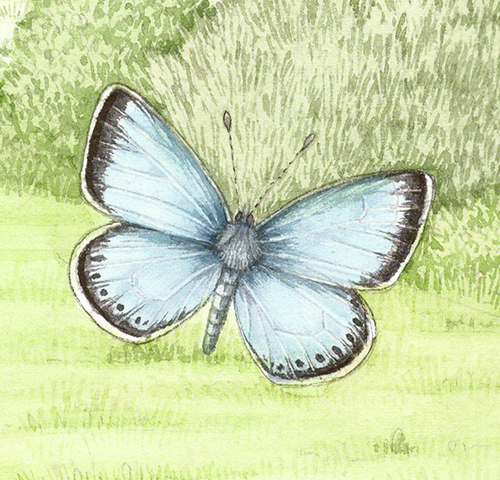

Common Blue

The Common Blue butterfly, Polyommatus icarus, is one of the most widespread of British butterflies, and can be found everywhere except the highest mountain tops, and north Shetland. It is unable to survive on improved pasture, so look for it on farmland where trefoil and clover crops are used instead of agro-fertilizers.

Common blues can be distinguished from other blues as their wing margins are white. Those of the Holly and Adonis blue have black stripes which stretch across the white, to the very end of the wing edge.

Females vary massively in colour. This is partly individual, and partly geographic and seasonal. They can be almost totally dark brown, or entirely blue. However, females always have distinctive orange edges to upper and lower wings.

The colour of Common Blue Butterflies

The amazing colour, a sort of iridescent lilac-blue, is due to various factors. The helicoidal structure of the scales causes light diffraction. This creates a “glittery” effect. (For more on iridescence in nature, check out my earlier blog). Pigments are synthesized and laid down days before emergence from the chrysalis. Then further pigments, which boost the absorption of UV light, are added. These are made from pigments in their food plants, flavonols. Female Common blues who have high concentrations of flavonols in their wings seem more attractive to the males.

Male Common blue specimen and illustration (see my blog for more)

Blue butterflies and Ants

Common blues interact with ants. The caterpillars and chrysalis emit tapping noises, or “songs”. These attract the ants who come and tend them. Others in the Lycaenidae family of butterflies also do this (check out my earlier blog for more on this). Ants are rewarded with sugary secretions. Unlike their cousins, the Adonis and Chalkhill Blues, these secretions are low in protein. Perhaps that’s why the Common Blue has less ants tending to it than the other species?

Possible confusion with other species

There are several species of Blue butterly in the UK, although none so widespread or common as P. icarus.

Chalkhill blue Polyommatus coridon is far paler, and has dark wing edges.

Chalkhill blue

Adonis blue, Polyommatus bellargus is a vivid, bright, glowing blue. It also has thin black stripes to the edge of the wing.

The Holly Blue, Celastrina argiolus, could be confused with the Common Blue, especially the males. However, the underside has no orange markings and is far paler and less busy than P. icarus. Yet again, the presence of black lines on the wing margins shows it cannot be the Common blue.

Holly blue female Celastrina argiolus

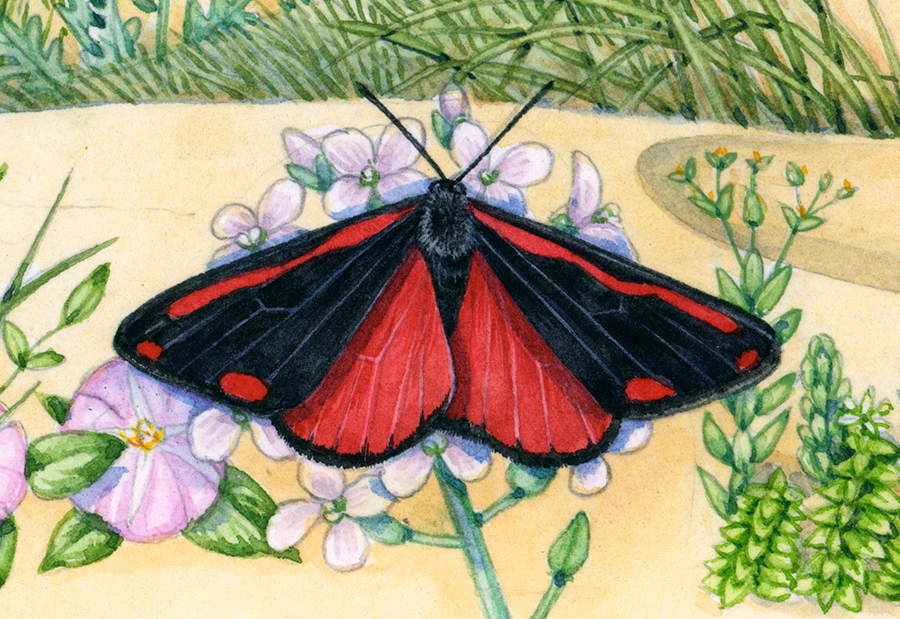

Cinnabar Moth

Our last species isn’t a butterfly at all, but an arctiid moth. The Cinnibar, Tyria jacobaeae, is a common sight in Coastal areas, and is strikingly beautiful.

With black forewings, edged with a red stripe, and crimson hind wings with a black border; this truly is an elegant insect. It’s name refers to Cinnibar, a red mineral derived from mercury ore.

Caterpillars are blatantly obvious, striped with yellow and black bands. They can be seen smothering their host plant, Ragwort Senecio jacabaeae (note the similarity in species name). They obtain toxic alkaloid chemicals from the ragwort, and this deters predation as caterpillars.

The caterpillars are voracious. They often devour the entire plant before pupating. This seems to lead to random acts of cannibalism.

In the USA, Cinnibar moths are used to control the highly successive invasive Ragwort. This seems to be working.

Ragwort Senecio jacobaeae

Possible Confusion with other species

There aren’t any other day-flying moths that look quite like the Cinnibar.

Burnett moths are also red and slate-black. However, they bear spots, not the wing bars seen on the Cinnibar.

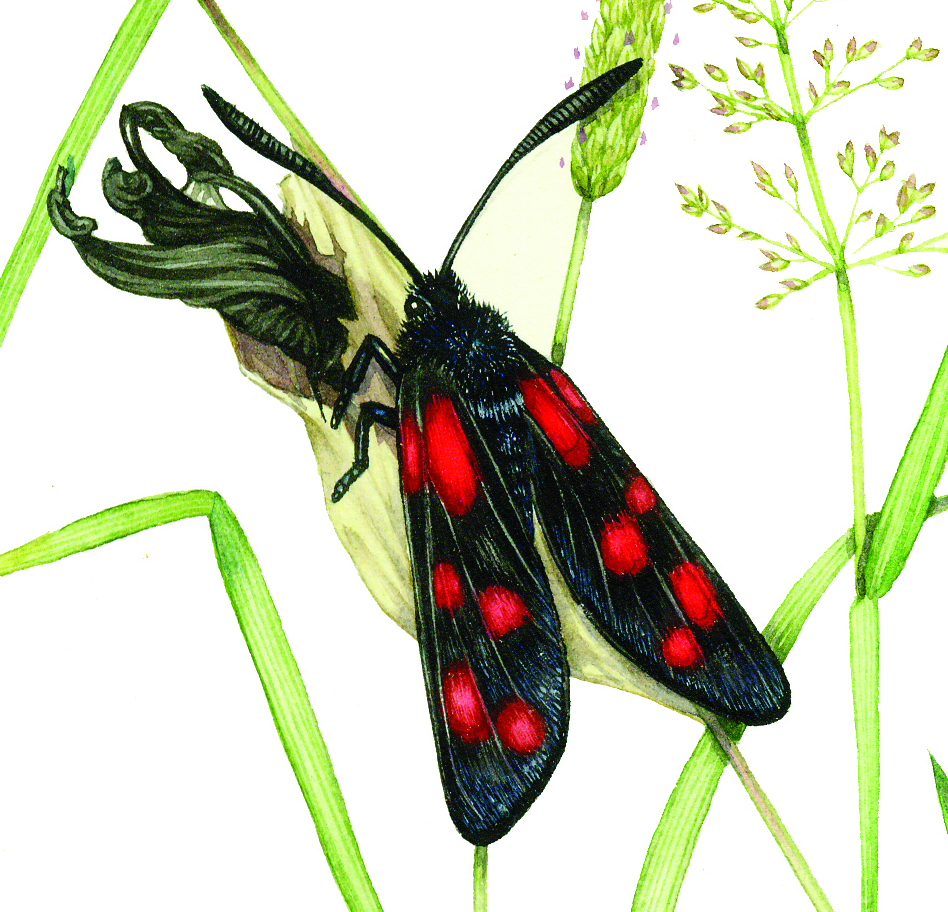

Six spot Burnett moth Zygaena filipendulae emergent adult

Conclusion

Spending a day researching four fairly common British butterflies and moths for this blog is a treat. There’s so much to learn about each and every species! I am indebted to “Butterflies of Britain and Ireland” by Richard Lewington and Jeremy Thomas. It’s a gorgeous book, and fascinating too.

It also gives pause for thought. Four insects, chosen only because of their shared habitat, are utterly fascinating. Expand this out to every insect, plant, bird, mammal, and microbe that one encounters… There truly is an endless source of wonder in nature. I’m glad this little corner of sand dunes in Bantham, Devon will be managed to preserve and encourage that diversity. And I’m so pleased that I have the chance to help share that vision with the public, through my illustrations.