Fungal treats at Cusop Churchyard

Fungal subjects always make my heart sing, so I was really pleased when three turned up in a recent species list I’ve been working on for Cusop Churchyard. Not only were these three species new to me, but one is considered extremely rare!

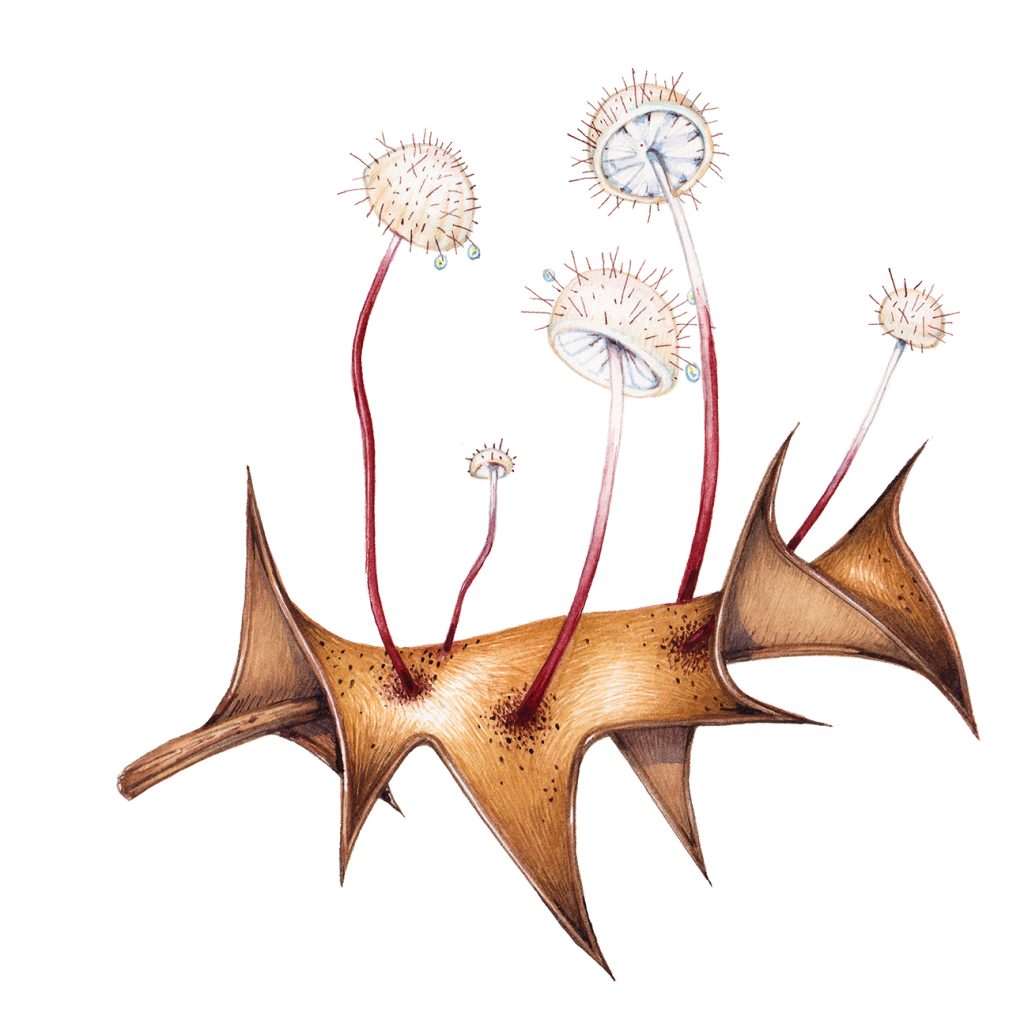

British earthstar Geastrum britannicum

The British earthstar is one of a family of fungus, the Geastraceae. Related to puffballs, they all have the same distinctive shape, with rays supporting a central spore sac. There are 15 UK species, and can be found in the colder months, making them a good target for winter wildlife forays. Many appear in churchyards, as with our British Earthstar.

They differ in the size and shape and colour of the spore sac, the way the rays (basal supports) present, and in habitat. For more on UK earthstars, check out the Discover Wildlife magazine article by wildlife author and naturalist Phil Gates.

British Earthstar: Species identification

Our British earthstar has a distinctive brown spore sac, carried high on a stalk above the rays. There are 4 or 5 rays; these are pale, and recurved, resembling legs. They grow out of matted hyphae and organic matter at the base of the fungus. The most important distinguishing features of this species are the ring and inner halo around the base of the beak (the pointed bit at the middle of the spore sac). The beak itself is grooved and erect when fresh, and is “fimbriate”, meaning it emerges from a fringe at the top of the spore sac.

British earthstar Geastrum britannicum

The spore sac sometimes has a mica-like patina on its’ surface, and sometimes a hanging loose collar appears. Spores are all smaller than other Earthstars, being 3 – 3.5 micrometers.

It’s easy to muddle up Earthstars, and it’s only when all these indicators are combined that you can assume you’ve got a G. britannicum. This is especially likely if the fungus you’re examining is growing in a graveyard, and near Yew.

This fungus was only “discovered” in 2015; before then it was probably lumped in with other Earthstar species. But for now, although mycologists believe it may well be quite common, it has only been recorded on a few UK sites. Including Cusop churchyard. It made newspaper headlines when it was first discovered!

For more on this Earthstar check out Jeremy Bartlett’s blog and photos; and for more on the discovery of this species, check out page 9 of the Herefordshire Fungal Survey Group’s spring 2015 newsletter.

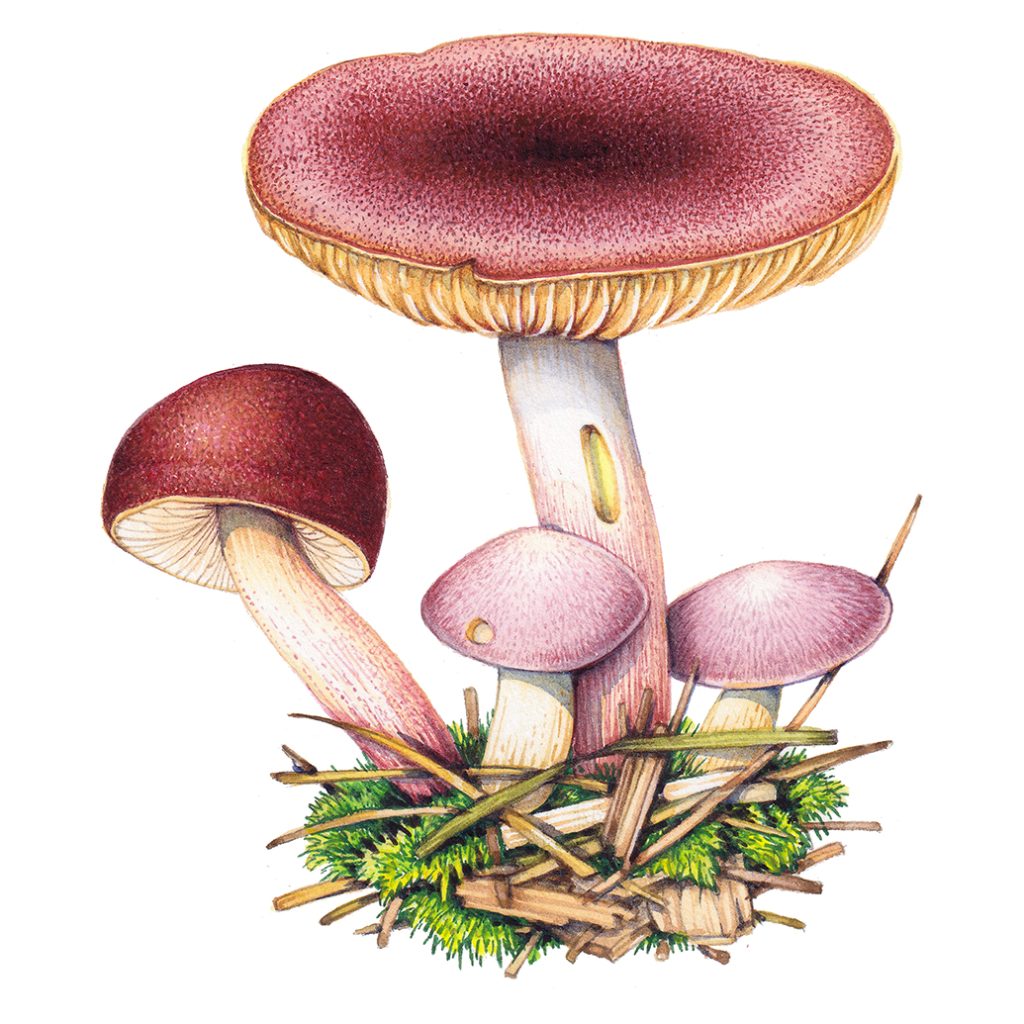

Plums and Custard Fungus Tricholomopsis rutilans

This is not a rare or newly discovered fungus, but is beautiful nonetheless. It’s a member of the Tricholomas family whose members include the Grey Knight Tricholoma pardinum and Coalman mushroom Tricholoma portentosum, among many others. They grow in woodland, and all have white spores, pale flesh, and mostly carry gills which grow into the stipe.

This species is found across Europe and in North America, and also Australia (where it’s thought to be a non-native introduction). Like many fungi, Plums and custard are saprophytes, feeding off dead wood.

Illustrating Plums and Custard

Plums and Custard: Species identification

Sometimes known as “Strawberry mushroom”, it has a very distinctive pink-red colouring. It grows amongst moss, often under confer trees (and Yew). Large groups are often clustered together, growing in thick green moss and looking very photogenic.

Gills are bright yellow, crowded closely together, and wide; however, the spores are white. Unlike many other Tricholomas, the gills barely run into the stipe . The cap colour is yellow thoroughly speckled with tiny red scales which are often seen emanating radially from the centre of the cap. The cap itself is convex and domed in young specimens, and flattens with age, occasionally becoming almost completely flattened.

In dry weather, the scales can crack into tiny mosaics of red, exposing the yellow flesh beneath.

Plums and Custard Fungus Tricholomopsis rutilans

Stems are white, or pale, with more red-purple scales, especially towards the base of the stipe. The fungus smells of rotting wood, and is not considered edible.

For more on this species, please check out the i.d page on First Nature’s site.

Holly parachute fungus Marasmius hudsoni

The first thing to notice about this fungus is how exceedingly tiny it is. Although considered rare, this is quite possibly because it’s so frequently overlooked.

A member of the Marasmiaceae, it grows on moist old holly leaves, often in the shelter of hedges.

The stems are slender and either clear or flushed red toward the base, and may have long hairs (setae). The cap is white and convex, although it may flatten with age, and has long setae scattered across it which catch water droplets. Caps are up to 5mm across, often much smaller. At the base of the stipe is an area of blackish rhizomes. Spores are white and tiny.

Unlike many other fungus, it doesn’t necessarily grow in groups, but often has quite a solitary habit.

For more on this beautiful little fungus, please check out First Nature’s page, where you’ll find the fabulous comment: “Culinary Notes: The Holly Parachute mushroom is so diminutive and insubstantial that any attempt to make even a mushroom morsel never mind a meal would be quite ludicrous.”

Holly parachute fungus Marasmius hudsoni

Conclusion

Doubtless there are many, many other fungi growing in Cusop churchyard. But these three were flagged up as the most fascinating, and unusual. What with the rarity of Holly Parachute and Earthstar records, and the beautiful colours on the Plums and Custard, it’s another reminder that we should keep our eyes open when we visit churchyards. Caring for God’s Acre is a charity dedicated to supporting nature in UK churchyards. They are well worth investigating and supporting. I also like their work because I was lucky enough to illustrate the lower plants and common graveyard wild flowers on an identification guide for them!

Brilliant piece Lizzie. I too have enjoyed the fungi and lichens in Cusop churchyard but I have never heard of the Holly parachute fungus so I will now look out for that. I also found Coral fungus and Orange Peel fungus growing in the churchyard, the latter on Richard Booth’s grave! Someone looking at the grave remarked that ‘some unfeeling person has chucked their orange peel on his grave’ until I pointed out that it was a fungus.

I love this! I lvoe the orange peel and outraged tourist. Can I add your observations to the blog? It’d be lovely to give folks a couple fo extra species to look out for.