Botanical Illustration: the achene

Natural science illustration and natural history illustration need you to understand what your subject looks like, and he correct words needed to describe it. Last week my blog was about fruit type definitions, inspired by some work I did for Rodale’s 21st Century Herbal by Michael Balick. Whilst getting my head around the terminology of fruit types, I realised there’s scope for a whole blog about the seemingly humble ACHENE.

Defining an Achene

The ACHENE is “a small dry indehiscent single-seeded fruit” (Flora of the Birtish Isles, Clapham Tutin and Moore). So far so good. Yet under this umbrella definition is an enormous amount of variety. The fruit of the buttercup and crowfoot is often referred to as a “typical achene”. A typical achene is a fruit containing a single seed, where the fruit wall has hardened around the seed inside and thus covers it like a coat (without sticking to it).

Creeping buttercup

Explaining that definition!

INDEHISCENT means the fruit won’t open to disperse the seed at maturity.

Achenes only contain one seed. Each achene is formed of this single seed produced by one carpel. A CARPEL is one of the units that the GYNOECIUM is made from. And a GYNOECIUM? That’s the female parts of a flower. It’s the ovary (which, when fertilized grows into the seed), the style, and the stigma.

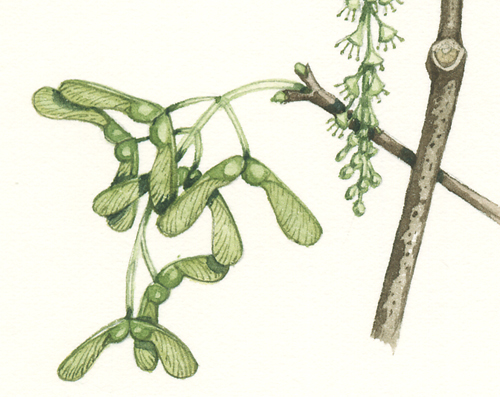

Winged achenes

Sometimes, an achene can have wings. If so it’s called a SAMARA. These wings are extensions of part of the tissue of the wall around the seed. It grows outwards and flattens. The purpose of these wings is to aid in wind dispersal, which explains why it’s mostly tree species who develop them. Wings can grow on both sides of the seed; as in the case of the elm, bush willows, and hoptree.

Elm with winged achene (samara)

Samara can also have one wing or extension, leaving the seed at one end of the wing. This is the case for maples (where these single winged samara are paired into the instantly recognisable shape), and for the ash.

Maple

The benefit for a tree of this design is that the seed “auto-rotates” as it falls, ensuring a clean and distant dispersal from the parent tree. When something auto-rotates, it means that it goes on rotating as it falls through air in a steady fashion (as un-powered helicopter blades would do). Try it next time you have a maple or ash key in your hand, it’s a nifty piece of aerodynamics.

Asteraceae and the achene

Asteraceae are plants made of two types of flower, ray and disk florets. A common example is the daisy, and the dandelion. Each yellow “dot” in the centre of a daisy is a single yellow disc floret. Every white external “petal” is a ray floret. Asteraceae species have different ray and disc florets according to species. Across the entire botanical family (which used to be called Compositae), CYPSELA are their seeds.

Here we encounter a slight hiccough. Some botanists claim that although cypsela are similar to achenes, they are, in fact, a different thing. This is because they’re produced from a compound inferior ovary with one locule. This means they’re produced by several ovaries which are joined together, each one of which is made of one chamber. The whole lot is sited below the petals and rest of the female flower parts.

Most botanists agree that a cypsela is very similar to an achene. They permit it to be used as the same umbrella term, hence it appears in this blog.

The dandelion seed, with its distinctive parachite, is a cypsela. The fluffy part is made from part of the calyx, whose tissues have evolved into the intricate flying machine which attaches to each seed.

The sunflower seed is another example of a cypsela . The white or striped cover of the seed is the wall of the cypsela fruit. Dissect a sunflower seed. See the hard outer coat and the seed inside; closely surrounded by -but not attached to- the fruit’s wall.

Within each rose hip, hidden amongst the hairs and the flesh, are a few achenes.

External achenes

For me, the most remarkable fact I found about achenes was they can be external. The seeds that pepper the outside of a strawberry are all individual achenes. Each one encases a single seed. The delicious strawberry that we eat is, in fact, not a fruit at all (each of the strawberry pips IS a fruit). It’s merely the sweet tissue which bears the achenes.

Other achene-bearing plants include: the tall anenome, cannabis, buck-wheat, crows-foot, lesser celendine, globe artichoke, spearwort, fleabane, zinnias, chrysanthemums, lettuce, marigold, echinacea… Considering how many plants bear achenes, I reckon it’s worth knowing what one is. Hopefully this blog has helped to explain just that.

very nice article good knowledge server

What fruit contains a single seed.

https://www.letsdiskuss.com/what-fruit-contains-a-single-seed

Hi Kirtan, thanks for sharing that link, much apprecaited.

Wedding Venues in Delhi is here to help you find and book the perfect place for your special day. We offer a range of wedding services to make your wedding planning easy and stress-free. We can also customize your wedding according to your budget and preferences.