Introduction to Lichens

Botanical illustration involves illustrating what are traditionally known as the “lower plants” as well as the green leafy ones. Lichens fall into this category (along with the very different mosses, and liverworts) although in fact they’re much closer relatives of fungi.

Lichen courses

Having been on a lichen course with Ray Woods, through RWT and written it up “Fungus lichens and dragonflies” I was keen to learn more.

I’m member of the brilliant Institute of Analytical Plant Illustration (IAPI) who organise workshops for their members, including one on lichens. This organisation promotes understanding between botanists and illustrators and is a really friendly bunch of enthusiasts and experts. If you’re into botany, or illustration, it’s well worth joining; I have learnt masses from their workshops and meetings and relish the chance to meet people with shared interests.

In July, I went on an excellent (and very reasonably priced at £10 for members) IAPI “Introduction to Lichen” course at RHS Hyde Hall.

This was taught by John Skinner, an eminent lichenologist with the British Lichen Society with a real ability to communicate his knowledge and enthusiasm in an accessible way. (He’s doing another lichen course at the FSC in September).

The images for this blog are from my sketchbook unless otherwise noted, and as such are rather simple and un-worked. Hopefully though, they’ll help identify the different types and a few structures of lichens.

Lichens vs Liverworts

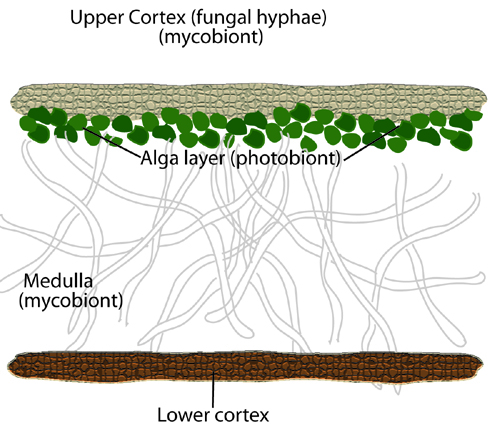

First we learnt the difference between lichen and liverworts, and that all lichen are a fungal species living symbiotically with an algal species. We next examined the basic structure of a lichen thallus cross-section: an upper skin or cortex with a layer of photosynthetic algae below (these are often referred to as photobiants). Next there’s the medulla which consists of the fungus’ hyphae (sometimes called the mycobiont), and a lower skin or cortex at the base. Below is a diagram of a cross section of a thallus.

Lichen are classified by their fungal partner, not the algal ones which, in many cases, are the same for many lichen species.

They also grow outwards from the centre; the oldest area of a lichen is its middle while the margins are often a different colour as these edges are the fungal hyphae reaching outward. Only a little later do the algal photobionts follow.

Lichen types: Crustose

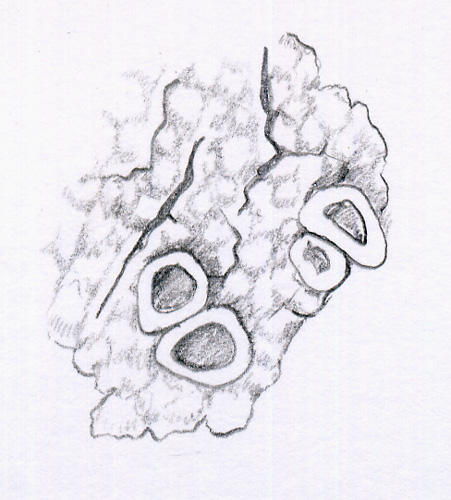

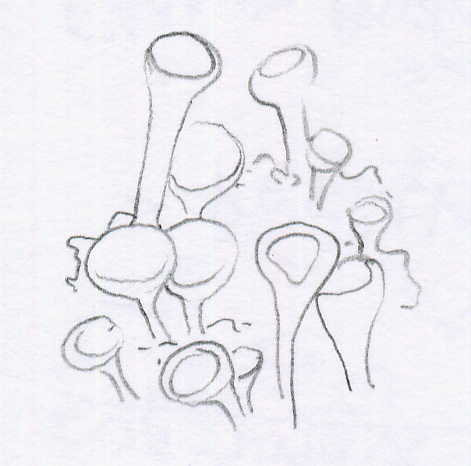

The lichen shape is vital in lichen identification. First, you get CRUSTOSE lichen which form a thin crust on their substrate. These are the flat coloured splotches you see on stones and tree bark (and are really hard to draw!)

This is an illustration of a crustose lichen, Lecanora chlarotera.

(The cups are sexual reproductive structures called apothecia, see below)

Lichen Types: Foliose

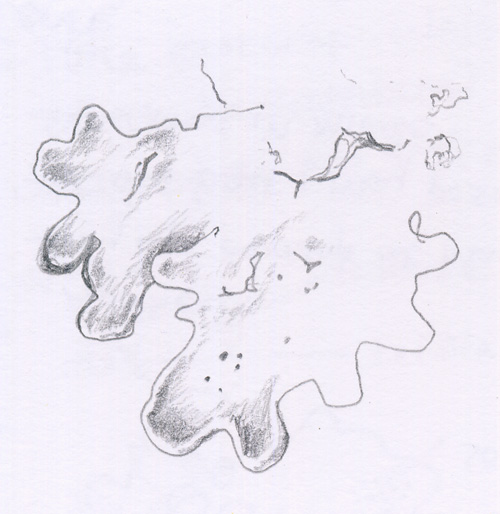

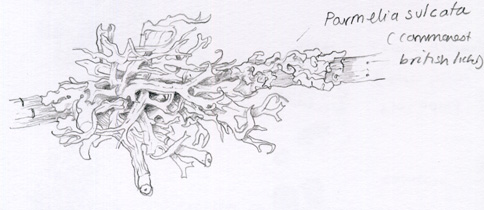

The next type is FOLIOSE which have thalli which can be lifted if you slide a finger nail under them. They look a little like flat flakes, and sometimes have “roots” (rhizines) on their under side.

Lichen Types: Fruticose

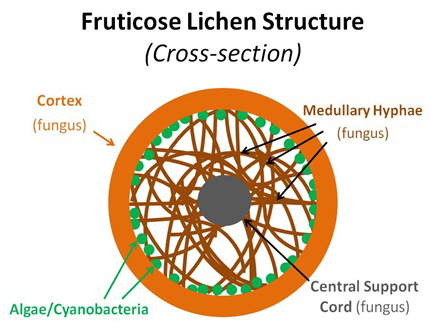

The most showy type are the FRUTICOSE species which attach to the substrate at one point, then form elaborate branching shapes which stand proud of the substrate and can look like tiny trees or a mass of tangling hairs. Their structure in cross section is circular, with the thallus layers forming around a central core rather like a gobstopper.

Image of cross section of Fruticose lichen from Watching the World Wake Up, which also has lots more great stuff on lichen.

Fruticose lichen (Evernia prunastre) with foliose lichen (Parmelia sulcata) below

Below are two examples of fruticose lichen painted by Christina Hart Davies who does some of the most beautiful illustrations of lower plants I’ve seen.

Other Lichen Types: Placodioid and Cladonia

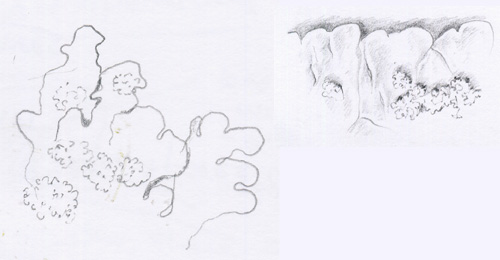

There are some other shapes too; PLACODIOID which are crustose at the edge and foliose at the margins;

SQUAMULOSE which consists of lots of little scales and are a variation of the crustose form; and CLADONIA which are squamulose scales with little upright feet (podetia) coming from them. These are often very pretty; the heathland lichen which are pale green with scarlet tips are cladonia lichen.

Lichen Reproduction

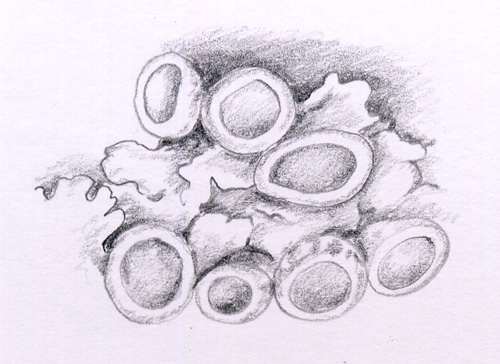

Next, we learnt about vegetative reproduction in lichen. The simplest form is a bit of lichen breaking off from the mother plant and growing in a new location (fragmentation). However, lichen have two other vegetative reproductive structures too. The first are SOREDIA.

A single soredium is a cluster of algal cells surrounded by a tuft of the associated fungal hyphae. They’re tiny, and look like tiny fluffy spots on the thallus. Position on the lichen margins or toward the middle of the thallus is important diagnostically. They’re spread by wind and rain.

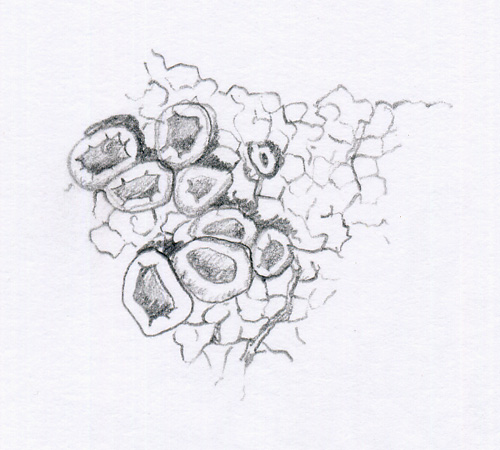

These are sketches of soredia on foliose lichen

Another vegetative method of reproduction is through ISIDIA. These are tiny pegs or outcrops which pepper the surface of the thallus, and are designed to break off easily and fragment, thus allowing colonization of new habitats.

Lichens can also reproduce sexually, by means of APOTHECIA (which are also found in fungi). These are cup shaped projections which have bags of spores within them. In damp weather these bags (or asci) eject their spores into the moist air. With age, these apothecia may become domed. Theyre often said to resemble little cups or jam tarts since they have distinct little edges.

Sketches of a foliose and a crustose lichen species showing apothecia

Illustrators of Lichen

The most glorious lichen illustrations I’ve found thus far are by Clare Dalby. Unfortunately I could only find very low resolution images of the two charts she’s done for the British Lichen Society Wall chart If you have an interest in identifying or illustrating lichen, or simply love beautiful scientific illustrations; these are well worth purchasing from the BLS.

Having done the lichen course, I now feel I understand the morphology of lichen and thus am far better equipped to illustrate these species as I know what characteristics to look out for. In fact, I’m rather looking forward to the next commission I get to illustrate lichen, especially if it’s a bright yellow one, a pretty cladonia, or something over-the-top and exuberant like Evernia prunastre.

Beautiful work.

I had a silly question – How does the algae receive sunlight if the the fungi has covered the outer skin completely.

Cheers from india

Dhruv

Architecture Student

Hi Dhruv

I dont think that’s a silly question at all, and I dont know the answer for sure. I believe the lichen grows on top of the fungi layer, not the other way around. But I cnat be certain this is the case in all situations.

Great question. Next time I meet with my pet Lichen expert I’ll ask him!

Thanks for the comment!

Yours

Lizzie

Lizzy, I need ur email address. Wanna talk you more on tropical lichens in Sri Lanka.

Regards

Lakshmi

lakshmi.nbotanicgardens@gmail.com

Good morning Lakshmi

Thats the sort of email I like! My email address in info@lizzieharper.co.uk. However, I should let you know that Im booked solid with work through the end of May. However, one of my friends who is also an illustrator might be able to help, if you have a tight deadline. She’s a specialist in illustrating lichens. But in any case, drop me a line, I’d love to hear what you have in mind!

Yours

Lizzie

Wow, I never realized how fascinating lichens are until I read this post! 🌿 The intricate symbiotic relationship between fungi and algae is truly remarkable. I love how lichens can thrive in extreme environments and act as bioindicators of environmental health. Learning about their unique ecological roles and diverse forms has sparked my curiosity to explore more about these resilient organisms. Thank you for sharing such an enlightening introduction to lichens! 🌱

Hi Evansmeade, my absolute pleasure!

I never realized lichens were actually a combination of organisms—mind blown! On my last hiking trip, I noticed some bright yellow patches on tree bark and had no idea they were lichens. Your section on air quality indicators was especially interesting. Are there any lichens that can actually help improve air quality, or are they just passive indicators of pollution?

Hi Edmon

I think lichens are helpful in improving air quality, as are all things which photosynthesize. And yes, how cool that they co exist! Im glad you enjoy that too