Wildflower families: Orchidaceae

Wildflower families: Orchidaceae, the Orchid family is the last in my series of blogs on common flower families. My online Field Studies Council course, delivered by Iain Powell, gave me the idea for this series. I do a lot of drawing and painting of wildflowers, so important that I learn more about their families, their similarities, and their differences.

For plant anatomy, look at the basics of botany blog, and at fruit types. What’s in a name 1 and part 2 discuss how Latin names work and why they are important

Some of the other families I’ve examined include the the Plantaginaceae (Plantains), Rosaceae (Roses), Ranunulaceae (Buttercups), Caryophyllaceae (Campions), Fabaceae (Peas), Brassicaceae (Cabbages), Apiaceae (Carrots); and the Asteraceae (Daisy family). The Orchids will be the last in this series for a while.

I am a botanical illustrator, not a trained botanist. So if you see a mistake, tell mw so I can fix it. Thanks.

Fragrant orchid Gymnadenia conopsea

Wildflower families:Orchidaceae

The Orchid family is the most profuse on earth with 760 genus and more than 28,000 species globally. They are members of the Monocots, along with grasses, sedges, rushes and lilies. As well as having simple leaves with parallel veins, often in a basal rosette; many also have swollen root tubers called pseudobulbs. There is much variety in the irregular flowers, but all have a mechanism for giving sacs of pollen to a visiting insect. These are known as pollinia. Seeds are tiny, held in a capsule.

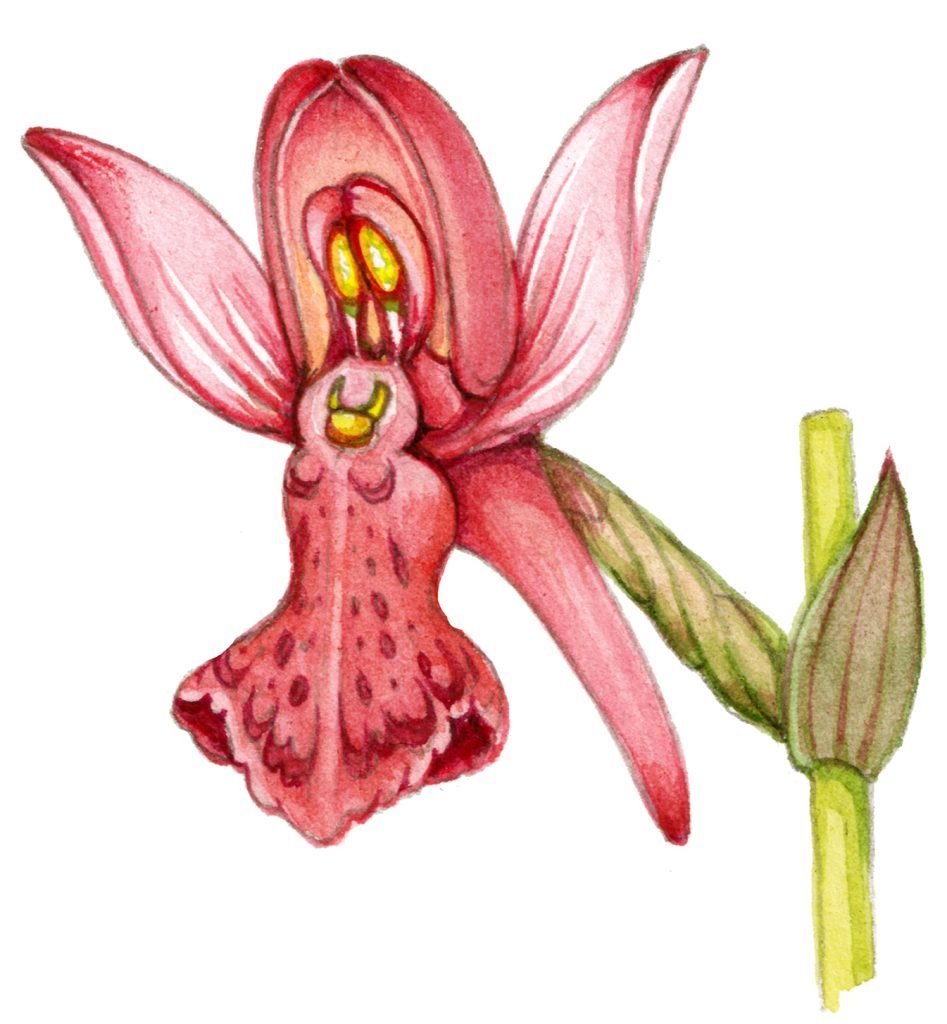

Early Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea

Orchids are considered exotic so are popular house plants. Many homes have a couple of Moth orchids, Phalaenopsis, on a window sill. Dendrobium, Cattleya, Oncidium, and Miltonia are other hot house varieties.

The flavouring Vanilla comes from the pod and seeds of Canilla planifolia which is grown commercially. Likewis, the starch-rich tubers of some Dactylorhiza and Orchis species are ground up and used for cooking and medicine.

Early Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea with swollen pseudobulbs

Orchidacea overview

Plants in this family have simple linear alternate leaves, with some reduced to scales. The veins are parallel.

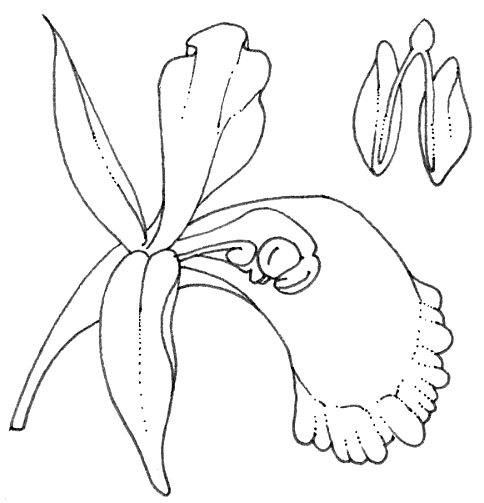

Orchid flowers are bisexual and irregular and amazingly diverse. They can be solitary or in a raceme. Generally, they consist of two whorls of 3, and often twist as they develop. Pollen is held in adapted Pollinia which are produced by one, occasionally two or three stamen. Ovaries are inferior.

Cretan orchid Cephalanthera cucullata

The name Orchidaceae comes from the Greek word “Orchis” meaning testicle. This refers to the bulbous shape of the swollen root or pseudobulb that you see in many species.

Early purple orchid Orchis mascula

Orchidaceae Leaves

Orchid leaves are pretty similar; all are simple with parallel veins, tend to be fleshy and don’t have stipules or a petiole. The leaves en-sheathe the stem. Leafless orchids reduce their leaves to scales and take an even more intimate relationship with mycorrhizal fungi which provide them with a lot more nutrients than in regular fungi-orchid symbiosis. In leafless orchids, roots are photosynthetic organs. (Many thanks to Max Rykaczewski for this clarification!) Some species have markings on the leaf, like the Spotted orchid Dactylorhiza fuchsii.

Common spotted orchid Dactylorhiza fuchsii

Orchidaceae Flowers

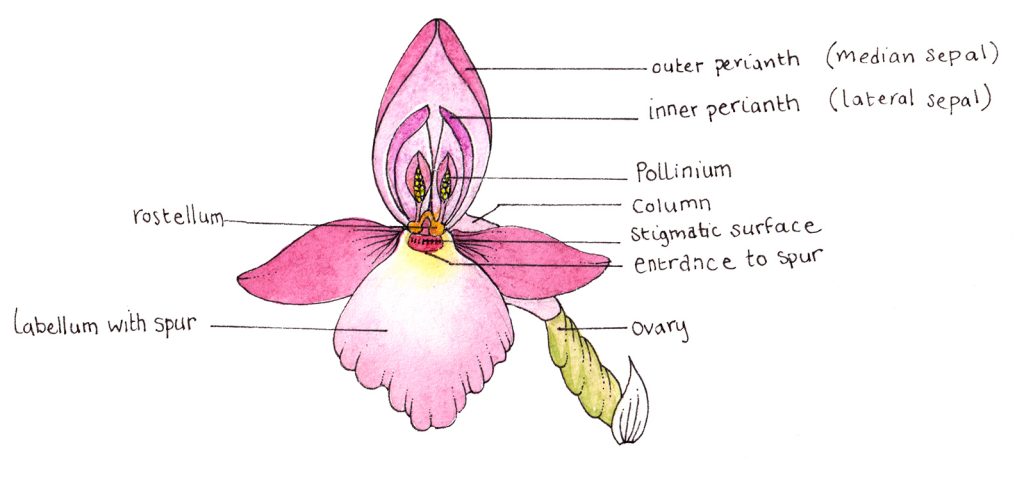

The two whorls that make up the orchid are an outer ring of Petaloids, and an inner ring of petals. Petaloids are a cross between sepals and petals. Outer and inner whorls often have the same colouring. One of the inner petaloids has a projection, like a spur.

Orchid diagram

Orchids also have a large lip. This grows at the top of the Orchid flower, but twists 180 degrees as it grows so that by the time the plant needs pollinating the enlarged labellum can act like a landing strip for pollinating insects. In some single-flowered Orchids, the flower stem bends back on itself and over the stem to achieve the same result. This process is called Resupination.

Orchid flower of Early marsh orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea

Pollinia can be highly evolved to dovetail with one specific pollinator. Sometimes the plant glues these sacs of pollen to an insect head, at other times to a bird’s beak. Smooth surfaces like eyes and mouthparts make good adhesion sites. The only birds that pollinate orchids are Hummingbirds, and although they pollinate a mere 3% of Orchid species, it makes for around 1000 species using bird pollination.

Diagram of a Pollinia and within an orchid flower

The plant produces a viscous glue, and once the pollinarium is attached, this dries out and rotates the structure into the ideal position for pollinating the next stigma visited. There is a pair of Pollinium per flower. For more on Pollinia attachment check out this brief overview from iNaturalist.

Orchid bee Euglossa cybelia with Cycnoches guttulatum orchid and pollinia attached to the abdomen

The ovary is inferior and has 3 fused carpels. Monocots often present floral parts in multiples of 3, eudictos in multiples of four or five.

Orchidaceae Fruit

Orchid seeds are produced in capsules which get shaken by the wind. Seeds are tiny, like dust, and are perfectly suited for wind dispersal.

Common lizard Lacerta vivipara in field with grasses buttercup and orchids

In the wild, seeds rely on symbiotic fungi to germinate as the embryo is tiny and there’s almost no endosperm for nutrient storage. Humans sometimes germinate them in sterile environments, in nutrient rich agar! (For more on germinating orchid seeds look at this Orchidbliss blog.)

Jersey orchid Anacamptis laxiflora

Orchidaceae: Other species

In the UK we have 15 common orchids, as listed in this BBC Countryfile article. Sometimes several species grow in abundance oat one site, like at Hartslock Nature Reserve where over 7 species grow on one slope.

Many tropical orchids are epiphytic, growing on trees, and acting like clambering vines.

Pyramidal orchid Anacamptis pyramidalis

Conclusion

I’ve never spent an enormous amount of time with the Orchids. When I see them growing in a field I am always delighted, but they don’t seem to fill the pages of my sketchbook. Perhaps it’s time for that to change. References for this blog and all the others in this series include my FSC botany course delivered by Iain Powell, the Common Families of Flowering Plants by Michael Hickey & Clive King, and the excellent Naturespot website.

Bee orchid Ophrys apifera

Hi Lizzie, lovely article about Orchids. They are close to my heart, as I spend years on studying them. One little thing need to be corrected. When you write about leafless orchids, you call them parasitic. In fact they are not. Years ago botanists used to think they are parasites on trees, but the truth is much more amazing. Leafless orchids reduced their leaves and take an even more intimate relationship with mycorrhizal fungi which provide them with a lot more nutrients than in regular fungi-orchid symbiosis. However it is worth to mention that in leafless orchids roots are photosynthetic organs. Wishes!

Hi Max

Thank you so much for this feedback, and for updating my research! I have tweaked the text in the blog, and am very grateful to you for taking the time to get in touch. I’ve popped in a link in the text to your profile on Researchgate, if there’s a different link you’d prefer me to use, just let me know.

x Lizzie

Thank you for mentioning me at your text! I’m glad I could help 🙂

My Research Gate profile is https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Max-Rykaczewski/research

My absolute pleasure. I’ve updated the Research Gate profile. Thankyou!

Hi Lizzie.

I have just watched in absolutely fascination your 2019 video of you painting a sprig of Rowan berries, in real time.

I attended One term of an art class almost 2 years ago, an was amazed how I was able to make a piece of fruit or a shoe or a fox come alive on what started as a blank sheet of paper.

I enrolled one to a second term but before it began I broke my right wrist. Then the class went into liquidation . I didn’t regain the courage to find another class.

I would really like to join your on line tutorials. Or at least to start have some information how to access what you have to offer.

I’m 75 in May but I feel I could follow your inspiring tutorials, I have no life experience of painting, since primary school..

Hi Gleny

Ah, you see! It’s never too late to start drawing and painting, whatever point in your life you’re at. What a shame your local class disbanded, it sounded perfect, and like it really made you realise just what you’re capable of. And the broken wrist – oh man. One of my good botanical illustration friends broke her wrist in November and is going stir-crazy not being able to paint the mosses she’s currently working on. Poor you.

I have a youtube channel with lots of step by step tutorials, feel free to visit and see what appeals. I try to upload a new one every couple of months: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCd_5uf3Zy8q0bLFy5b5PHiw

I’m also working on a couple of “how to” books, due to be published in 2027. No doubt I’ll shout about them on my blogs once they’re published!

It sounds to me like you’ve really got the bug, so I think if you can, you should feel brave enough to find another art class. Having done a bit of teaching, I can assure you that all that’s needed is enthusiasm and the will to try. And you’ve already got that!

I’d also suggest you buy some ok art supplies, especially if you’re doing watercolour. Nothing crazy posh, but a decent brush (maybe a Princeton Neptune number 1 or 2 size), a little set of watercolours (nicer than what they give you at school, they often have “Student” grade. For example choose the Cotman watercolour set rather than the much more expensive Winsor & Newton professional ones. Unless you fancy splashing out, that is!). And some hot press smooth watercolour paper. Maybe a sketchbook too.

But the main thing is to do it, and it sounds like you’re already up for that.

Good luck!

x

This was a fascinating overview of the Orchidaceae family. I especially enjoyed the explanation of pollinia and the way orchids adapt their flowers for specific pollinators—it really highlights how complex plant–insect relationships can be. As someone who often reads botanical content while supporting students with plant science coursework, posts like this make it much easier to understand real examples from nature. Thanks for sharing such detailed observations and illustrations.

Thanks Lily, glad to be of use!