Spotted Plants and Fungi

Spotted plants and fungi is one of a series of blogs on patterns, follow the links for an overview of pattern, more on stripes, leaf variegation, and a step by step of a variegated geranium leaf.

How are spots formed?

Spots in plants are caused by areas of darker pigmentation, usually red anthocyanins. Plants sometimes have paler spots on their leaves which are caused by an absence of chlorophyll and are discussed in my blog on Variegation. This blog will focus on a few species with spots as I could never hope to cover all the spotted plants in one blog (or one lifetime!). The spots seen on fungi relate to their anatomy rather than the chemistry of their colour.

Orchids

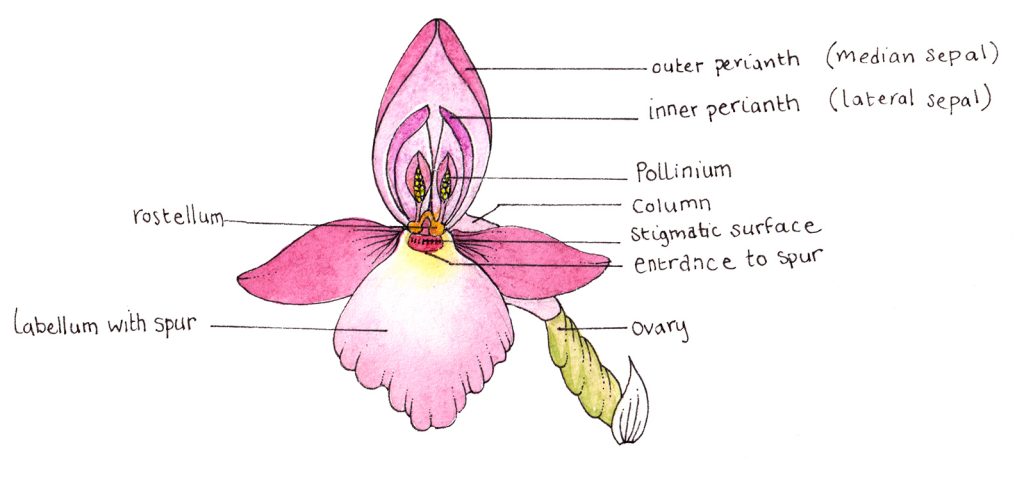

Many orchids have dark spots on their lowest petal, the labellum. The labellum is the landing pad for potential pollinators and its shape plus these markings attract insects. Most orchids are pollinated by beetles and hymenoptera. These insects assume they will access nectar produced at the labellum base and in the spur behind the flower, but in many cases Dactylorhiza orchids are food-deceptive, luring the pollinators in (and being pollinated) without giving them a nectar reward. (First Nature)

Diagram showing the position of the labellum

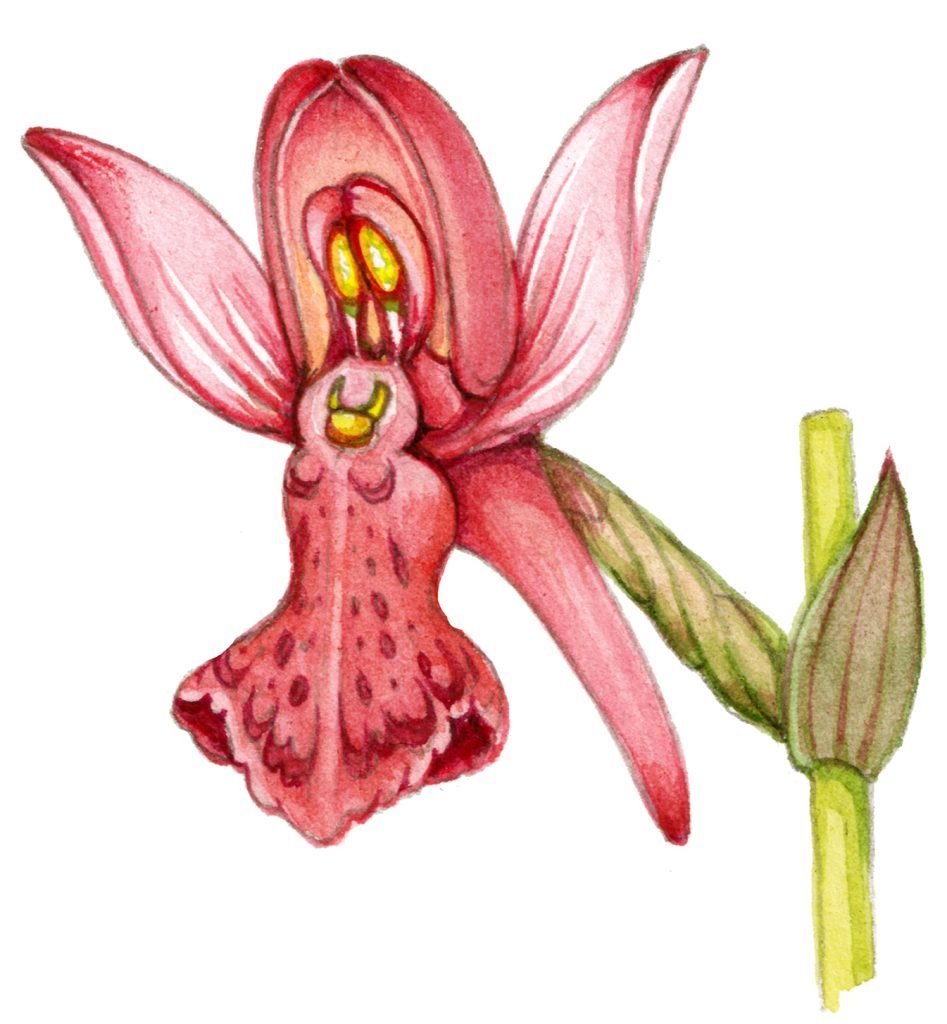

Orchids: Early Marsh Orchid

One orchid that does this is the Early Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea. Each flower has a pattern of spots on the labellum, guiding the potential pollinators to the pollen-producing heart of the flower.

Early Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea

Plants growing in areas with less nectar-producing neighbours, such as heaths and bogs, do better with their trickery than those surrounded by flowering plants who deliver on their visual advertising. (Dactylorhiza incarnata and deceptive pollination by Lammi and Kuitunnen 1995 in Oecologia)

Orchid flower of Early marsh orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea

Orchids: Common spotted orchid Dactylorhiza fuchsii

The Common spotted-orchid appears early in the year and not only has spotted flowers but also spotted leaves. These are not always present, in plants with paler flowers these are less likely to appear. There is variation in the leaves, both in the intensity of the colour and the number and shape of the spots. In some plants, there will be a paler area within each spot, giving the plant a leopard-like appearance. The spots are created by the purple anthocyanin which may also flush the stems and leaf tips red. The spots run cross-ways to the longitudinal veins.

Common spotted orchid Dactylorhiza fuchsii

Heath spotted orchid Dactylorhiza maculata and Southern Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza praetermissa are closely related and may also have spotty leaves and flowers.

Heath spotted orchid Dactylorhiza maculata

Orchids: Bee orchid

It would be hard to find a spottier orchid than the Cycnoches guttulatum. This epiphytic plant attracts the Orchid bee Euglossa cybelia and glues its pollen-filled pollinium onto the insect, ensuring cross pollination with other plants of the same species.

Orchid bee Euglossa cybelia with Cycnoches guttulatum orchid

Perforated St Johns wort Hypericum perforatum

St. John’s wort is also spotted, but this is not to do with pollination. The little “holes” that pepper the leaves of this plant are glands which contain a cocktail of hypericin and other chemicals. These are thought to dissuade insects from eating the leaves.

The flowers also have spots, or little dots. These are black, and appear of the edges of the petals. You can also see them on the calyx edges, and they appear in many Hypericum species.

Slend St. John’s wort Hypericum pulchrum

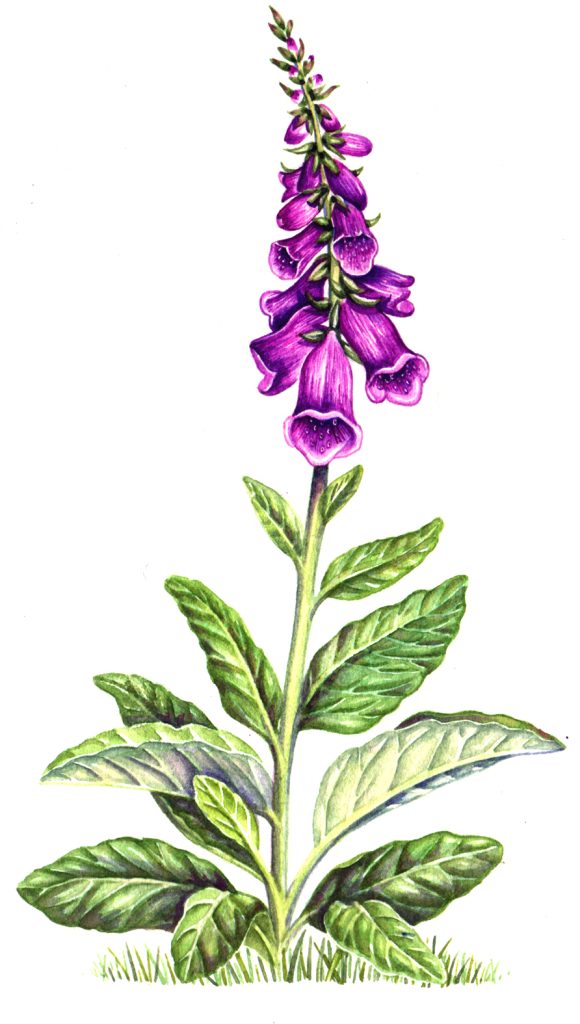

Foxglove Digitalis purpurea

Nectar guides appear on flowers to guide pollinators to the centre of the flower. Many are invisible to us as they operate within the spectrum of light that bees and butterflies use, which includes UV light. You can see these if you shine a UV torch on open flowers at night. However, some flowers have spotty nectar guides that are easy for us to see. One example of this is the Monkeyflower Mimulus bolanderi, another is the Foxglove.

Foxglove Digitalis purpurea

Nectar guides radiate outward from the nectar reward and the high contrast also helps attract potential pollinators. Foxglove are interesting as they have a guard system to help keep out insects who would like to take their nectar but would be unable to carry pollen and help in pollination. At the throat of each flower there are a few stiff bristles which prove no problem to bees and bumble-bees but deter smaller insects. In fact, the hairs might help bees scramble into the flower.

Flower of the Foxglove showing the nectar-guide spots

Another way foxglove select their pollinator is by having the nectar reward at the very base of the flower. This means only long-tongued bumblebees such as the Garden bumble bee Bombus hortorum can access it. However, some bees bypass the security system by chewing holes in the base of the flower and stealing the nectar. For more on Foxglove pollination, check out Ray Cannon’s blog.

Foxglove Digitalis purpurea flower with White tailed bumble bee Bombus leucorum

Research proves that nectar guides are important. When covered up, the scent and shape of flowers still attracted pollinators. But there was a significant reduction in the percentage of those who inserted their proboscis to access nectar and then to pollinate the flower. (Dennis Hansen 2011 Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Floral Signposts)

Lamiaceae: Skullcap

The Lamiaceae or nettle and mint family also have clear spotty nectar guides on their lower petals. This can be seen clearly in the Skullcap Scutellaria galericulata.

Skullcap Scutellaria galericulata

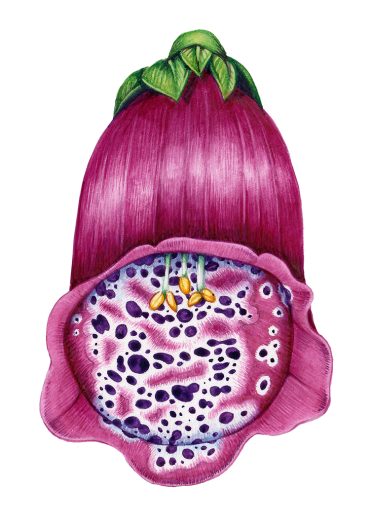

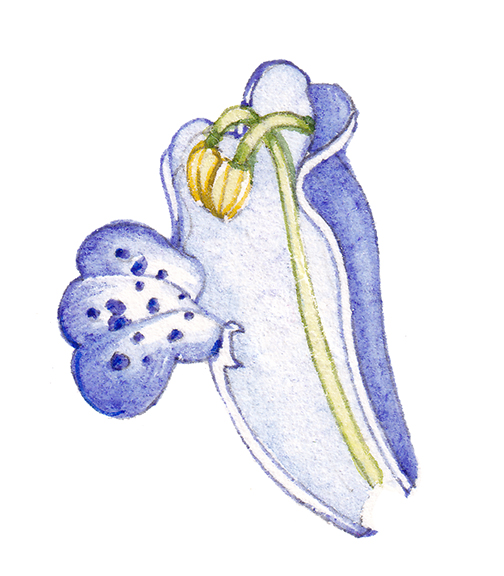

In cross section, you can see the position of the pollen-laden anthers, directly above the spotted landing pad on the lower corolla lip. In many of these flowers, the weight of the visiting insect will cause the flower to rock forward and deposit pollen on its back. (For a more detailed look at the mechanics of these levers take a look at Floral Construction and Pollination Biology in Lamiaceae by Claßen-Bockhoff in the Annals of Botany 2007)

Cross section of Skullcap Scutellaria galericulata

Lamiaceae flowers are pollinated by bees 66% of the time; but ants, hawkmoth, flies, and butterflies also play a part. (Shrishail Kulloli in Nectar guides in Lamiaceae, Current Science 2011).

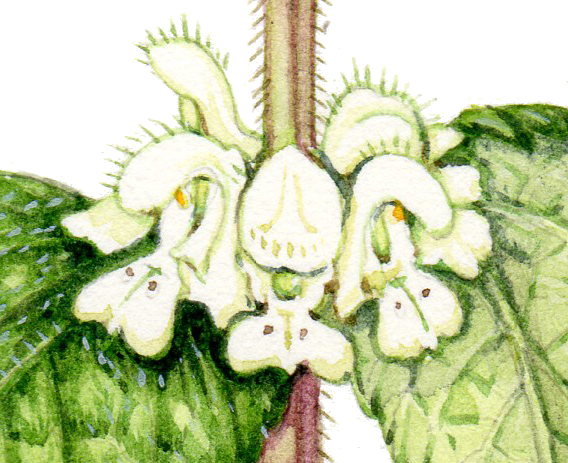

Lamiaceae: White deadnettle Lamium album

The White dead nettle also has small spots on its lower corolla lip. In this case they’re green dots against white.

White dead nettle flowers Lamium album

White dead nettle also attract pollinators with scent, oil, lipids and polyphenols. (Lamium album and nectar guides by Aneta Sulborska-Rozycka et al 2023 in Micron).

Fungi: Fly agaric Amanita muscaria

It feels wrong to put a fungus in at the end of a blog about flowers as they are a whole other kingdom. However, one HAS to include the Fly agaric in a blog on spots.

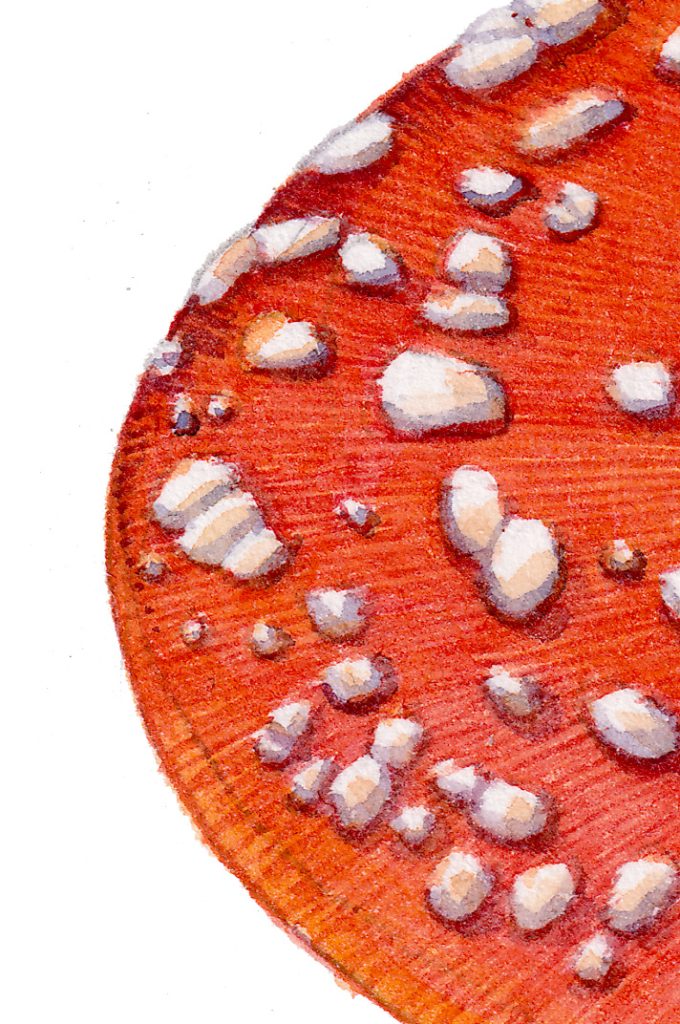

Fly agaric Fly agaric Amanita muscaria

The distinctive white spots on the cap of this iconic fungus do not seem to have any purpose, or not that I found literature on. They are remnants of the universal veil, a white sheath that covers the fungus’ fruiting body as it grows from the ground. The toadstool breaks through the sac, and small warts of white tissue remain. These may wash off in the rain.

Fly agaric Amanita muscaria cap

Fly agaric are poisonous and packed full of hallucinogenic chemicals. However, the red colouration doesn’t seem to suggest toxicity in fungus. The Ox tongue fungus Fistulina hepatica and Crimson waxcap Hydrocybe punicea are both red and edible (the latter is rare so please don’t eat it).

It is interesting that such a stark colouration on a toxic fungus seems to have no link to warning colouration. Such a pattern on a beetle, fish, or butterfly would probably be a warning of toxicity.

Completed illustration of Fly agaric with materials

Conclusion

This whistle-stop tour of spotted plants and fungi has shown that the most common reason for spots on plants it as a nectar guide for pollinators. However, some spots are glands and others, such as the warts of Fly agaric, appear by chance.

Whatever their purpose, the spots that we find on plants and fungus are both stunning and a treat to illustrate.

Great illustrations!

Thankyou!