Wildflowers of Braunton Burrows

A recent commission involved illustrating 30 species for Braunton Burrows, a very beautiful sand dune system in North Devon’s AONB. The main challenges were the timing of the job, during winter when none of the flowers were in bloom, and their unfamiliarity to me.

However, I really enjoyed illustrating such a pretty and diverse selection of plants.

Evening Primrose Oenothera biennis

It’s rather surprising that I’ve not illustrated this blousy yellow flower earlier, it’s common and it also grows in my garden.

Painting yellow flowers has its challenges. How to make the petals look clean and crisp, but still show lights and darks? How to avoid them looking orange or green as you add the shadows? (For more on this, please look at my Painting yellow flowers blog).

One of the lovely details of this plant is that the stem has glandular hairs on the stem, emerging from scarlet spots (which explains the close-up).

This plant has flowers that only open at dusk, hence the name. They’re pollinated by moths, butterflies and bees on the look out for nectar.

Evening primrose seeds are rich in oils which are used to treat Premenstrual symptoms and some skin complaints, such as psoriasis.

Sea stock Matthiola inuata

This is a really pretty plant, and capturing the soft green of the leaves meant using a lot of white, something I usually avoid. I’ve not seen it growing in the wild (it’s not that common), so had to work from photos.

Sea stock flowers in the late summer in the UK, and grows in the shingle line, just in front of vegetated dunes. It grows alongside Sea holly, Horned poppy, and Marram grass.

The basal leaves have distinctly wavy margins. The pale leaves and four-petalled mauve leaves make it an easy one to identify as it’s not similar to other sand dune species.

Sea Pansy Viola tricolor ssp. curtsii

I had some trouble with this plant, as different botanists had different ideas as to whether or not the flowers had purple on their petals. After consulting with the botanists and ecologists working at Braunton Burrows, we settled on the flowers having all yellow lower petals. The petals have purple striations, but the lowest petal is seldom blue or violet. This conflict between different botanist’s ideas is not uncommon. It’s something, as an illustrator, you have to negotiate with care.

The growth habit is low, and sprawling. Often in the wild these plants are partially buried in the sand, which is something I couldn’t easily represent in a cut-to-white illustration.

The sepals are longer than they are wide, and the whole plant has a bushy appearance. For more on the Sea pansy vs the Field pansy, check out the excellent Wildflower finder page.

Lesser Hawkbit Leontodon saxatilis

The Hawkbits are always a big challenge as they’re easily confused with Hawk-weeds and Cats-ear. In fact, all the yellow dandelion-like plants can be tricky to tell apart. You need to have good guidance from the experts, and decent image reference (or the plant itself to work from).

In this case, the leaves have forked hairs (you need a microscope to see this) and the under side of the petals are often flushed a greyish purple.

The leaves are slightly blueish and form a basal rosette. They have wavy edges. The stems don’t have bracts or leaves.

The seeds are distinctive too, as there are two types. On the outside are achenes with almost no pappas. The inside seeds have much more elaborate pappas with lateral hairs.

It’s important to add these details to an identification illustration as they can be really helpful when it comes to telling similar species apart.

For more on Lesser Hawkbit, visit the Naturespot site which is an excellent resource for UK animal and plant species.

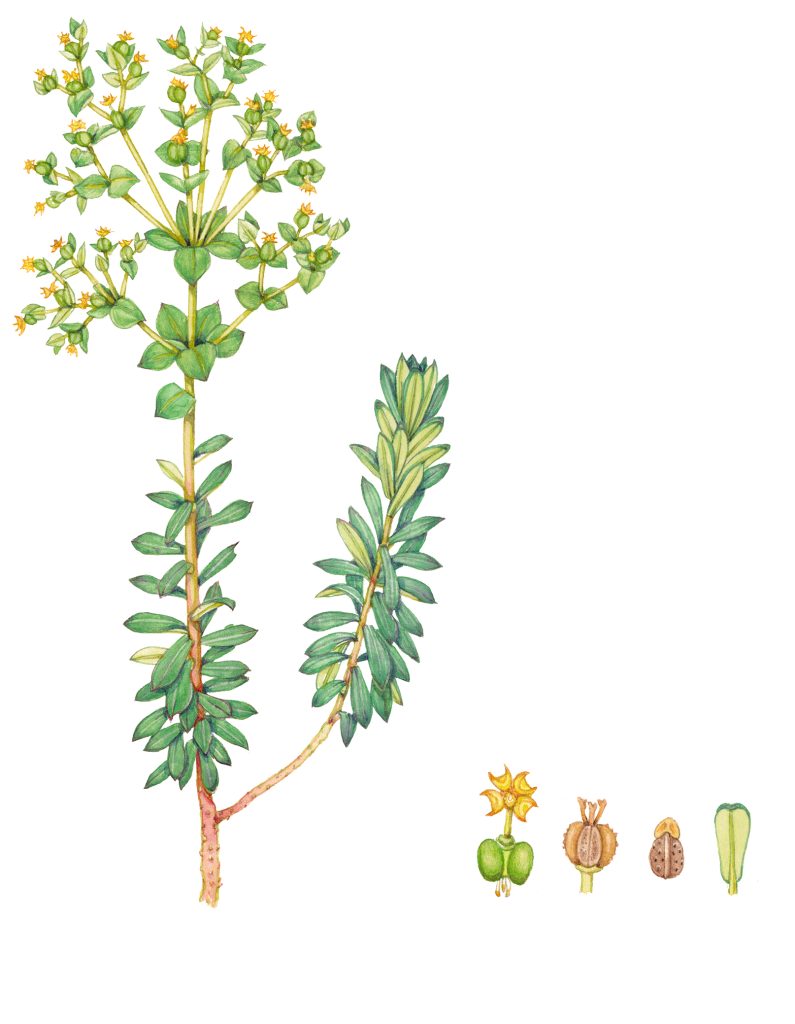

Portland spurge Euphorbia portlandica

This pretty little plant, stocky and low-growing, isquite localised. It grows on sea-facing sand dunes, including Branuton Burrows.

Telling this spurge from other species is less tricky that you may imagine, although they live in the same habitats. It’s a matter of size. Sea spurge Euphorbia paralias is much taller, and scarcely branched. Out Portland spurge is a small plant with lots of branching stems. Truth be told, this illustration probably needed a few more branching shoots.

Sea spurge also flowers later in the season and has less yellow flowers. The bracts below the flowers have a tiny point which is absent in sea spurge. They also have quite obvious central ribs, if you turn the bracts over. .

I very much enjoyed working on the non-flowering shoot, there’s something intensely satisfying about all those closely packed leaves. As with Sea spurge, the stems are often flushed crimson. Some mid-stem leaves sometimes have this colouring too.

For a good comparison between Sea and Portland spurge, check out the Wildflower finder’s page.

Round-headed Club-rush Scirpoides holoschoenus

One of the rarest plants illustrated for this commission is the Round-headed Club-rush. I was very lucky to have eminent botanical illustrator Christina Hart-Davies lend me some preparatory sketches she’d done of this species, years ago. Working with her reference is reassuring. She doesn’t draw things wrong.

This is quite a substantial plant, growing to 3ft tall. It can be identified by the clumped, round seeds and single elongate bract below the flowering stems. The seed-heads are in globe0-shaped groups, with lateral ones emerging from one central one. They are borne on short pedicels.

As many of you know, I love illustrating rushes, grasses, and sedges; so this was a treat to work on. the main challenge is getting the edge of the straight stems right. It usually involves holding my breath!

Although really quite rare in the wild in the UK it can be bought for garden ponds and marshy habitats, so perhaps its distribution is set to increase?

Bog pimpernel Anagallis tenella

This is probably the prettiest of all the plants I illustrated for this commission. The veined little flowers are almost round, opposite leaves are really charming. Again, it’s a plant I’ve never seen growing in the wild, however, I’m now keen to go and seek it out.

The flowers are very fragile, and have longditudinal veins on their petals. Inside, the stamens form a filamentous froth that looks fuzzy and white. As with many dune plants, they grow by creeping across the substrate using rhizomes. They root all along these stems, giving them a more secure hold of the substrate.

The flowers have a long flowering season, from May through September. They close at night, reopening at dawn the following day.

Seeds grow within the calyx of sepals, as a capsule.

Although mostly found in marshes, they appear on west-facing sand dunes too, as with Braunton burrows. For more on this pretty little plant, check out First Nature’s blog post.

Western eyebright Euphrasia tetraquetra

When I read this flower’s name, no lie, my heart sank. The Eyebrights (Euphrasia) are notoriously difficult to tell apart. They have tiny leaves and little white flowers, and often small details such as growth habit is used to tell similar species apart. The BSBI does have a handbook on them (which always suggests a challenging family group), but unfortuneatly I’m yet to get hold of a copy. It’s BSBI Handbook 18 and is called Eyebrights of Britain and Ireland, by Metherell & Rumsey, and is the result of years of painstaking research.

I used the online form of this handbook as a starting point in my research. It’s also known as the Seacliff or Maritime eyebright, and has colonised the USA. Many of the sites I consulted were American wildflower ones (such as the Native Plant Trust). This is not uncommon, there’s a lot of cross-colonisation of native wildflower species between Europe and the Americas.

The main indicators here are the growth habit, very condensed leaves, and stocky. The leaves are crammed together towards the top of the plant. It’s branches and the leaves are frequently tinged purple. As with other eyebrights, the leaf shape is a useful species indicator, although not fool-proof. The fact that many are recurved is also helpful.

But in truth, when I was done with the eyebright I let out a sigh of relief.

Sharp rush Juncus acutus

I started off badly with this plant, mistakenly thinking it was the Sharp-flowered rush, Juncus acutiflorus. Plants with similar names is one thing, but when the latin names are also very similar…it’s easy to make errors.

Sharp Flowered Rush Juncus acutiflorus

No. The Sharp rush is a different plant altogether.

It grows across the UK, colonising damp spots, and grows across most continents.

It’s easy to recognize for a couple of reasons. The first is how big it is. It’s much taller than other rushes, reaching up to 100cm. It also is a distinctive dark green colour, with clear longditudinal ridges. But perhaps the most striking feature is how stiff and sharp the leaves are. Reference book after reference book referred to this, and many begged keen botanists to look out for their eyes as the tips can do serious damage. In Australia it’s considered an invasive weed, and children are warned away from it because of the sharp spikes (Brickfield’s site).

Sand hill Screwmoss Syntrichia ruraliformis

My favourite plant in the list is the Sandhill Screwmoss. I’ve written a short, separate blog (!LINK!) on this as I was so taken by the species. This extraordinary moss looks utterly different depending on whether its wet or dry.

When wet it has distinct green star-like tips to its’ shoots. The mass of the moss is brown or yellowish. Apical points make the moss look slightly hairy, or whitened.

But when dry, it all curly up on itself and looks like little twists of wool. Such a massive transformation is not unheard of, but it’s very striking. I definitely had to illustrate this species twice. Luckily, thanks to Simon Norman (who works at FSC Publications), I had living specimens to work from.

Mosses are always the hardest species to illustrate, but I do love them. Perhaps because they require such a high level of concentration and detail.

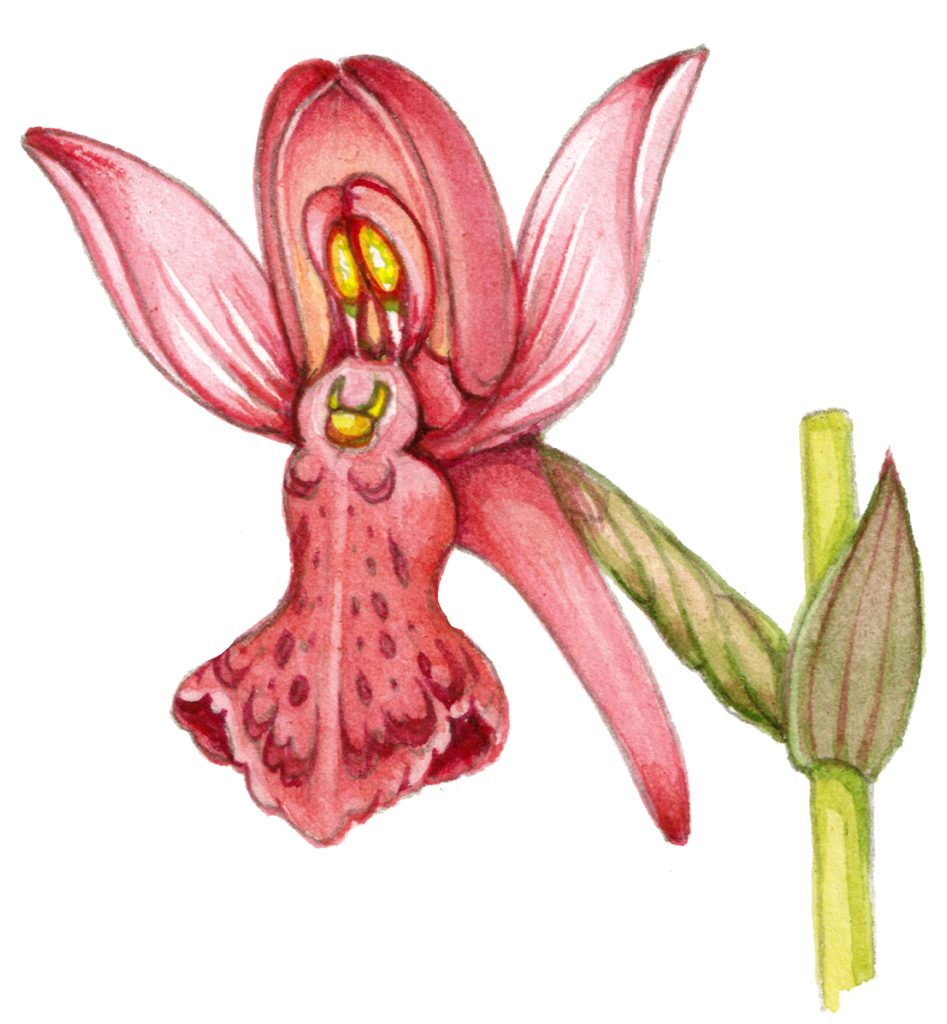

Early Marsh Orchid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp coccinea

The Early marsh orchid was interesting and the flowers are almost scarlet. This is rather uncommon in nature, unless the flowers are pollinated by birds. Insects (unlike birds) aren’t so good at seeing bright red on the spectrum. For more on how plants make different pigments, and why, check out the Cambridge University Botanic gardens video by Beverley Glover.

Orchids are such peculiar plants, and these are no different. Each flower is fully twisted around to provide a good landing-site for an insect. So they’re upside-down. I spent a long time on this plant, and made a step by step youtube film of me illustrating it, along with a blog.

It’s probably the most unusual plant on the list, because of the colour. I spent a while researching basic orchid anatomy before illustrating it. I’ve painted them before, drawing what I see, but this time I wanted to understand the form.

Although I was satisfied with the finished product, it wasn’t one of my favourites of the finished illustrations.

Conclusion

The diversity of species needed for this job was a treat. We had a few pretty flowers alongside the challenge of moss and rushes. Technical work with plenty of research was needed for the Sea pansy, hawkbit and eyebright. I enjoyed almost all of the plants required. And now I just have to be patient while the text is being written. And look forward to seeing the finished identification chart as and when it’s produced.