Illustrating Invasive Plant Species

Natural history illustrators have to do natural science and botanical illustrations of both beneficial and of problematic invasive species.

Many times, the reason a plant or animal is causing problems within an ecosystem is because it doesn’t belong in that system. It hasn’t evolved in equilibrium with the other species there, and thus out-competes them. This may be because it’s been introduced from another part of the world and subsequently invades. This is why we use the terms “invasive” and “introduced “ species.

This blog will look at three of the most problematic invasive plant species currently threatening British water ways. These plants are the Giant hog weed, Japanese Knot weed, and Himalyan balsam.

Plants create problems for canals and rivers (and other habitats) by out-competing native species for sunlight, water, and space. They can choke the waterways with their rapid growth. This will kill other plants that colonise and stablise canal and river banks; and can lead to big increases in erosion.

Invasive species: Giant hogweed

The Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) is a monster amongst umbellifer plants, growing up to 5m tall. It has an umbrella of tiny white flowers in summer and a hollow, ridged green stem. This is sometimes flushed or spotted with purple. It has large divided leaves.

Its height shades out other plants, killing those which help bind the banks of waterways together and slow erosion. Originally introduced to ornamental gardens in the 19th C, it soon proved an opportunistic coloniser. Spread is along streams and rivers using its water-borne seeds. It is now illegal to plant or transplant Giant hogweed outside of gardens, and has been since the 1980s (Wildlife & Countryside Act 1981).

Gaint Hogweed Heracleum mantegazzianum

It has a beautiful froth of white flowers, and looks like cow-parsley on steroids. However, the Giant hog weed has sap which can burn skin if it is exposed to sunlight. Before the toxic sap was known about, children would get blisters as they used the hollow stems to make pea-shooters or telescopes.

You can get rid of Giant hogweed by digging it out, or, at a push with weedkiller. All skin must be carefully covered if you’re handling it to avoid the threat of blistering. The RHS advises only cutting it down on overcast days to reduce the reaction the sap has with sunlight.

Invasive species: Japanese knotweed

Japanese Knotweed (Fallopia japonica) can grow up to 2m tall. It has alternate smooth green leaves, and climbs. Flowers are little, fluffy and white and can be seen in autumn. Stems are crimson red and hollow.

As before, the problems posed by this plant mainly relate to it out-competing native species for space, light, and water. With the ability to grow up to 2cm each day it’s a veritable rocket of a plant. It rapidly shadows then kills other species whose roots are involved in binding river and canal banks together. This leads to an increased risk of erosion.

Japanese Knotweed Fallopia japonica

Knotweed began life in Europe as an introduced garden plant, taken from Japan, Taiwan, and China in the 19th C. Now it smothers wasteland, waterways, and the edges of roads across the country.

It is particularly difficult to eradicate as it can regrow from fragments of as little as 1cm in length, so cutting it down is a bad idea. You are now required to eradicate it from your garden by law (the Crime and Policing Act 2014 insists on it). When you try to eradicate it from your garden, all parts dug up are classed as “controlled waste”. This means it mustn’t be put out with other garden or household waste. It must be disposed of at designated landfill sites. Glyphospahte weedkiller is recommended by the RHS.

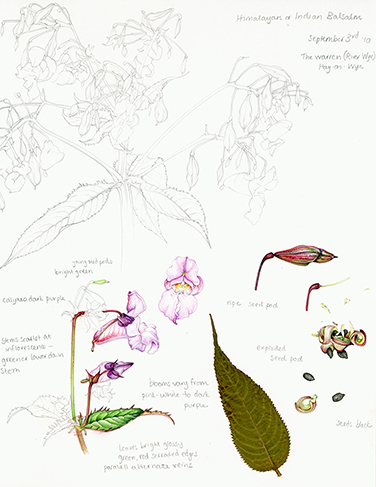

Invasive plants: Himalayan balsam

The last of this terrible trio is actually a very beautiful plant. Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera). It can be identified by its pink spotty slipper-shaped flowers, tall scarlet ridged stems, and slightly toothed lance-shaped leaves. In autumn they produce amazing seed pods which fire the seeds long distances (up to 7m!) when touched. It’s almost impossible not to give into the temptation to “pop” the seed pods.

Sketchbook study of Himalayan Balsam Impatiens glandulifera

It’s yet another example of a plant first introduced to make a garden pretty (in 1830 – Wildlife Trusts UK). It escaped and has now colonized much of the UK

If you’ve walked along a river bank in much of Britain recently you’ll have seen thickets formed by Himalayan balsam. They out-compete most other bankside species, including grasses. This results in erosion when the balsam dies back in autumn. It has prodigal spread as each plant can produce 800 seeds. However, it can safely be uprooted and left to decompose on site. If you get the plant before it seeds then there’s some chance of success as Cornish trials suggest seeds can only be viable in the soil for 1 year.

Himalayan Balsam Impatiens glandulifera

These plants were illustrated for an article in Gridline, the magazine of the National Grid (electricity) who have to maintain power cables and supplies across land and water which is often choked by these three invasives.

For more on these plants, please follow the links to the Wildlife Trusts pages: Giant hogweed, Japanese Knotweed, Himalayan balsam; and for information on invasive species of the UKs waterways, please check out the Canals and Rivers Trust link.

For more of my sketchbook studies of plants, please visit the gallery page.