Scientific illustration: Getting reference

It is a trueism that “you are only as good as your reference.” As a practitioner of scientific illustration, I am always searching for good reference of both plants and animals. You never know what the next job will ask for, so need to be prepared for any request.

Plants get sketched and details noted, in my botanical sketchbook studies. If a job requires illustrations of people (say, a hand in a gardening step-by-step vignette) I have my body and family to draw from. But animals? They move. They’re elusive. And when there’s a deadline looming, sourcing good ref. can be a real headache. Here are some solutions.

Photos & Sketchbooks

The most obvious action is to keep sketchbooks, and to take photos. I often ruin family days out by zoning out and spending ages watching the habits of, sketching, and taking photos of a bird or a bee. A good photo can be the basis of a polished scientific illustration, as with this nuthatch which came to our bird feeder.

If you work from photos it is vital to double check the anatomy of the animal against other reference. It is also vital not to simply copy someone else’s photo unless you have their express permission to do so. Without this, you’re infringing their copyright, which is illegal. Many natural history photographers are more than happy to allow you to work with their photos, but you do need to be sure to approach and ask them before putting pencil to page.

Insect Specimens

A dead insect should always be gathered and kept, preferably in a box with mothballs (to prevent them being devoured by museum beetle, originally a scavenger, but now a real pest of preserved zoological specimens). You can pin them to keep them safe, or just keep them in a sealed container. I scour window sills, and friends’ greenhouses and conservatories. Here’s a small sample of my finds (the dragonfly was brought back from the Phillipines, all the others are native to the UK).

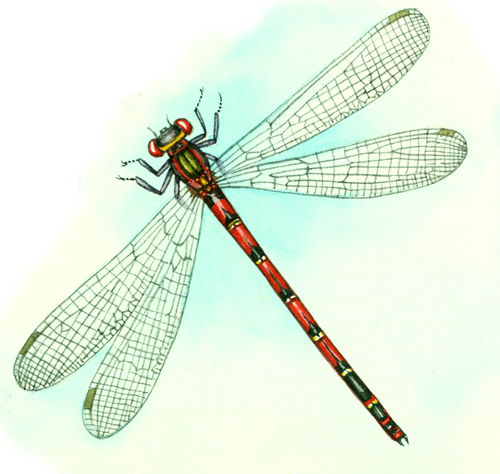

This large red damselfly I did for BBO Wildlife Trust was illustrated using a dead specimen; the body and thorax weren’t much use as colours of the odonata are very fugitive, but the wings were invaluable for details of the venation.

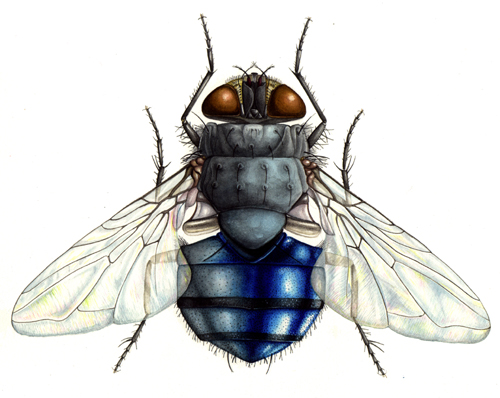

If you can find a live specimen of an insect you need to do a scientific illustration of, you can slow it down without doing it any lasting damage. You can do this by putting it in the freezer for half an hour (do NOT forget about it as it’ll freeze to death if left too long!) It is still, and then groggy as it recovers, which often gives you the time you need. This bluebottle was drawn from a fly slowed down in this manner (and a partial fly I found on a windowsill).

I used to collect insect specimens; running light traps, setting pit fall traps and traveling with a tiny killing jar. These days I tend to avoid this as I prefer to borrow rather than collect, but on occasion I still get reference this way. It is paramount to ensure that the species you collect is not only common, but also common in that specific area; and vital to collect the bare minimum of specimens.

Museum Specimens

Many museums have enormous archives of animal specimens, mainly generated by enthusiastic Victorian gentlemen naturalists, who peppered the country and collected zoological specimens with gusto. They are often willing to allow you to work from these if you come in and visit, and in some rare occasions may lend a specimen rather as a library lends a book. This smooth snake scientific illustration was done from a pickled specimen which lived in the fridge for a week or two.

As well as stuffed specimens (be aware that the final stuffed animal may have very little to do with shape of the living animal) they often have “skins” which are amazing to work from. Liverpool Museum has a wonderful collection of bird skins which I worked from when preparing illustrations of wading birds for them back in 1995.

Bones and Shells

Skulls and bones are invaluable reference, and some of the commoner British mammals (such as rabbits and sheep) readily distribute their mortal remains across the countryside. I’ve also found stoat, duck, heron, and badger skulls (look out for evidence of TB in these, it shows as areas of malformed and porous bone). Shells and sea debris can be picked up from the beach and stored, as can clean bones.

However, if you need to extricate bones from a dead animal, there are some ways to do so without getting your hands dirty. First, you can place the skull on top of an active ants’ nest. This is the method I used to clean my stoat skull. You can also bury the remains, and about a year later you’ll have a clean skull (this is how I got my perfect and very fragile sparrow skull. Stoat and sparrow are pictured above.) We even unearthed a dog skull in the garden, doubtless some long-gone and well-loved pet.

These skulls were used to illustrate a comparison of mammal teeth for the Complete Naturalist by Nick Baker and were all done from my own reference materials.

Road kill & Corpses

This approach to gathering reference may be rather unpalatable to those of a sensitive disposition; but the specimens I’ve gathered from road verges, and from generous friends who collect corpses on my behalf, have proved invaluable.

Birds and mammals killed by cars are often in near perfect condition, and can be stored in the freezer in zip lock bags. Currently we have a robin, a thrush and a swallow, some sparrow fledglings, a mole, a hedgehog, a shrew, and a greater spotted woodpecker in our deep freezer. (For more on this please take a look at my film Bird, bugs and bodies in the freezer) The shrew (again, for the Bumper book of nature) and woodpecker were my main ref for these illustrations below.

Many of these specimens are given to me by friends who generously find and pass them on. Thanks are due to Layla of The Majestic Bus, Simon Dale, Hannah at Hay Vetinary Group (who has promised to pass on any wild animals brought into the vets which don’t survive), and Abigail Roscoe.

One of the most exciting gifts was a clutch of Daubenton’s bats which has clambered out of the roof space and, alas, died in the attic. They had also dessicated, so are in effect mummified.

Once the local Wildlife Trust had been notified, I was able to keep the specimens. They were incredibly useful when painting a Daubenton’s bat for RWT’s Gilfach reserve, for the detail of the wings, colour, and ear structure.

So although challenging, getting good zoological reference is not impossible. Butter up your friends as they collect on your behalf. Ask natural history photographers nicely to allow you to use their photos. Keep a sketchbook. Take your own photos. But above all, keep your eyes open and never let an opportunity to glean more reference material pass you by!