A Visit to Cranfield Paint Factory

Visting the Cranfield paint factory was an absolute treat – the perfect combination of being wowed by the manufacturing processes, and being taught an enormous amount about a subject that I was already fascinated by.

My friend Lucy, founding member of AGNES, arranged the visit. AGNES encourages ecologically sustainable practise within the arts community. Lucy is currently reaching out to colleges, and reckons that visits to a paint factory like Cranfield would be a great way for students to get to understand materials, and to learn to respect and conserve them.

Empty tubes for oil paint, awaiting filling

Introductions

Cranfield colour is in Cwmbran in Wales, and after introductions and a cup of tea we were given an excellent lecture by the managing director of Cranfield, Michael Craine. This oil paint and printing inks manufacturer has been in the same family for three generations, and I have rarely seen a more friendly company. Everyone we met seemed pleased to see Michael, and to love their jobs. The atmosphere was great.

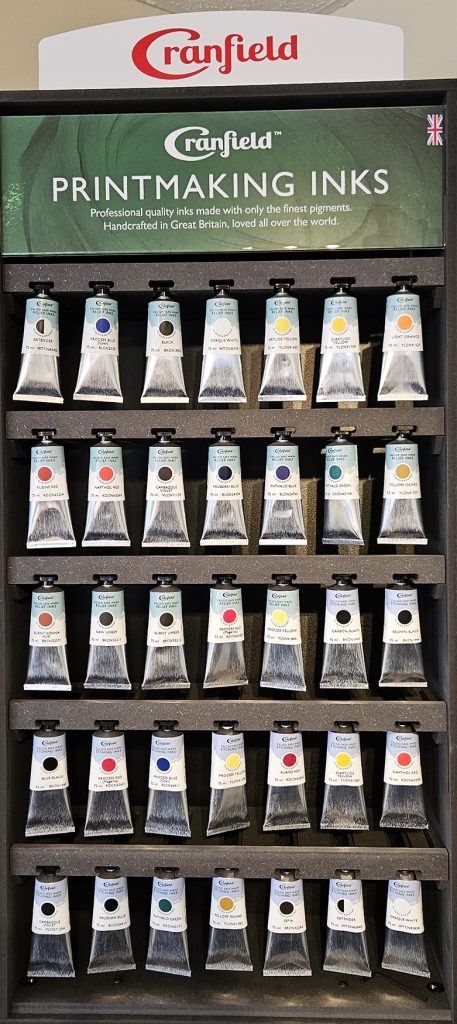

Cranfield’s range of oil colours

Cranfield no longer makes acrylics because of the paint’s need for fungicides and pesticides, and because they are, in effect, single use plastics. We also heard how logos (for example, one showing the company was environmentally responsible or carbon neutral) can be misused, mostly on imported art materials.

Then Michael introduced us to the three “M”s are Mixing, Milling, and Matching.

The Three “M”s: Mixing: The pigments: Carbon blacks

Mixing occurs between the pigment and a vehicle, in this case linseed oil. The vehicle wets the pigment, changing it from a powder to a paint.

Pigments come from three sources. The first are Carbon blacks. These have always been, and are still, made from soot. Burning different things creates smoke and the soot is deposited then collected from chimneys that run sideways to the furnace. Soot is fluffy and absorbent, so readily mixes with the vehicle to make paint. Carbon black from a furnace is used to make the lovely rich black etching ink, Black 1810. The slightly paler “Bone black” is made from burnt bone.

Mid Black etching ink tins awaiting their labels

The Three “M”s: Mixing: The pigments: Earth pigments

The second source of pigments are Earth pigments, collected from soils. These include ochres, umbers, and siennas; and occur naturally in the earth. However, there is variability in seams of earth and other trace elements occur with the pigment. They are also gritty, which wears down the milling machines. One trace element is iron which speeds up drying. Interestingly, the only watercolours I’ve ever had which have cracked have been Yellow ochres, probably as a result of this fast drying.

The Three “M”s: Mixing: The pigments: Organic and Synthetics

The final source of pigments is organic and synthetic pigments. Synthetics replace pigments which may be very expensive, or difficult to obtain for political reasons. For example, most of the lapis lazuli that can be made into Ultramarine is found in Afghanistan. They are also cheaper and more stable than some organic pigments, and are often less prone to fading. Interestingly, these synthetics are made by the same companies who make pharmaceuticals, and with the same levels of care. Cranfield source their synthetics from the EU.

A note here on Cadmiums. Some yellow paints are made with Cadmium sulfide, an inert substance which can cause no damage to human health. None are made with the metal Cadmium which is carcinogenic and highly toxic. This means I don’t need to worry about licking my paint brush after all!

Cranfield’s range of printmaking inks

Mixing: The Vehicle

Cranfield mix their inks and paints with linseed, (also known as flax) Linum usitatissimum. This wonder plant (and wonder mixing vehicle) is not only a beautiful blue, and very good for health if eaten; it can also be woven into linen, and provides the perfect oil to mix with pigment. The roughage and mucilage is removed, and after being boiled without oxygen the oil is ready for use. It is imported in big oil drums to Cranfield, stacked high in the warehouse.

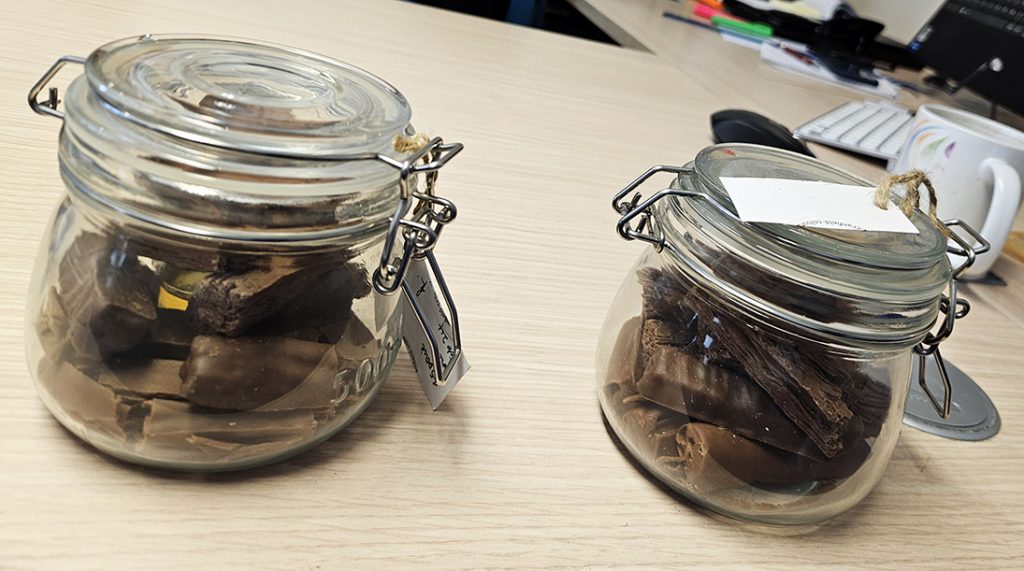

Chocolate absorbs odour and can be used to test linseed oil. If the chocolate smells ok, the linseed is ok. If it smells rancid and sour, then the linseed is probably off which will affect the paint mixture. These testing jars are on the desk of Paul Lee, the technical director.

The Three “M”s: Milling

Once you’ve mixed your colours, you mill them. This involves grinding them into tiny, evenly distributed particles. Clumping leads to uneven colour, and further clumping, and also means the paint struggles to dry.

The mix is forced through microscopically thin gaps between three rollers, moving at different speeds. In truth, the product is pulled apart to evenly distribute the pigment in the matrix mix, rather than being squashed. The pressure is 1000 psi / 70 cm squared.

Pink printing ink being milled through the three milling wheels

Paint can be manufactured using a cheaper process known as “bead milling”, crushed by loads of ball bearings. It produces a less consistent mix with lots of flocculation (lumps). and is not a technique used by Cranfield.

The Three “M”s: Matching

This was fascinating to learn about. How do you produce a paint which is consistently the same colour?

Michael taught us about Metamrism, “a scientific phenomenon the describes when two colours appear to match under one light source, but not another” (Wikipedia). So something that looks olive in one light may look brown, bright green, or pinkish in another. The standard light in which colours are assessed is something called “North sky” (also known as D65), similar to a diffuse light given when the sun is behind a cloud. However, modern bulbs can be tungsten, far closer on the colour spectrum to infrared, and LEDs which give out pulses all over the light scale. Modern lighting is a bit of a nightmare for paint manufacturers.

The photo above shows jars of pigment under North sky light (on the left) and a more purple light on the right, an extraordinary change in appearance.

The paint is also matched to be sure there is consistency of strength of colour, opacity, and in rheology.

The Three “M”s: Matching: Rheology

Rheology is the science of viscosity (something’s reluctance to flow) and tack (ability to adhere). These are different. Honey has low viscosity, it’s very runny; and high tack, it’s very sticky. Butter from the fridge has high viscosity and won’t flow easily; and very low tack. These inverse relationships are common and are important for paint manufacture.

White oil paint coming off the mill, showing how high its viscosity is

One way to decrease viscosity and make your inks flow easier is to add energy, either by stirring or by heating them. This property is referred to as being thixotropic. Another variable to juggle when matching paints and inks.

Other things to match include printability, drying time, resistance to rubbing, light fastness, odour, and fineness of grind.

Tour of the factory

After our lecture we got to look around the factory, seeing pink etching ink being milled, and how a vat of white oil paint has a thick enough consistency to allow a palette knife to stand bolt upright when dropped into it.

We also saw tubes being filled by hand, each with its open base ready to take the correct amount of paint or ink, then the tube being crimped closed..

Base of a tube of oil paint being crimped by a machine

There was a fascination to seeing boxes of empty tins of paint and tubes ready for filling. And hearing how darker pigments are stored in different areas, and that each colour can be produced for 4 – 6 week stretches before moving to another hue. One of their 8 sets of milling wheels is only ever used for white oil paint, and we got to scrape and test the consistency of it with a knife.

Large vat of white oil paint

Labelling the paints

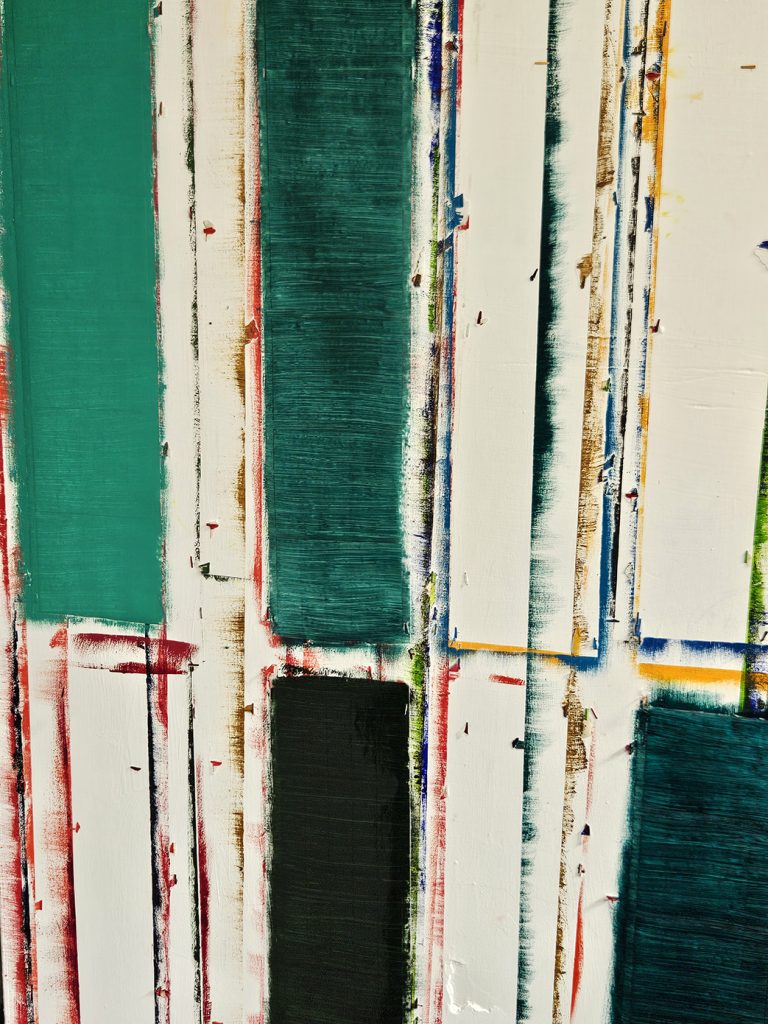

I loved the labelling of the paint tubes. Each one has a hand painted strip of colour on it. You can see the brush strokes on these colour swatches. These are produced on large sheets of paper pinned to an old door, then cut into the right size for the tubes.

Paints used to produce the colour swatches on each tube

To avoid confusion, each tube, tin, or can is labelled immediately after filling with a pricing gun. The team interpret these numeric codes and attach the right labels and colours.

Some of the paint strips on a door, they get cut up and put onto individual tubes

Each tube is then put into a little cardboard box with information on the range as a whole. Other than the paint tube lids, there’s not a speck of plastic packaging in sight, suggesting that Cranfield really do take environmental concerns seriously.

Part of an enormous order of purple oil paint being packaged up for Dick Blick art suppliers in America

Testing the paints: Different tools

One room has lots of tools to check the consistency of each batch of paint. Many are very old fashioned, like the Hengmen gauge. Each batch of paint has a dollop tested on this simple tool. You simply pull the squeegy downward on the metal sheet then see if there are any bumps or scratches in unexpected places. If so, the paint may not be milled fine enough.

Hengman gauge in use

They also use a Clear Weighted Plate (see the film below) which compares two paint splotches left by a rolling wheel on a metal bed. It helps show how liquid the paint is.

Clear weighted Plate in use

There are also lots of differently lit cabinets to double check for constant colour matching in different lights, metamrism,, and colour guides to check against.

Finishing up the tour

We left with a generous parting gift, and a real sense of a firm that produces incredibly high quality product in a traditional way, and in a wonderful work space. Michael was so very good at telling us about the physics and challenges of paint creation at Cranfield colour. Lucy and I left feeling very inspired. It is no surprise that Cranfield supply some of the best known artists’ shops across the globe; from Cass Art to Jacksons and Cowling & Wilcox, to Dick Blick in America, Rittagraph in Spain, and Jackson’s here in the UK.

Cranfield’s Managing director Michael Craine plus a member of the paint mixing crew

And, although I don’t use etching inks, printing inks, or oils; next time I take out my watercolour paints I’ll have a better understanding and respect for the work, research, and love that has gone into their creation.

Below is a short film from Cranfield’s Youtube channel showing some of the processes described in this blog (including use of the Clear Weighted Plate). They also produce a podcast which is well worth a listen.

Very interesting! And well written: I feel as if have been there myself. Thank you

Thank you Michael!

Yes the lighting aspect is great. I grabbed a new tube of Manganese Blue Hue watercolour- this time from Daniel Smith and about fell off my chair to realise it glows under black UV light. Whatever they added to their paint to have it do this isn’t on the label!

(Many animals are detectable with black UV. Scorpions and even platypus do. Other mammals do too like rodent, um, pee. You can also use it indoors to check if your cat’s peed where they shouldn’t and after you’ve cleaned it up to check your cleaning job!)

Ps don’t underestimate the importance of crimping tubes properly. My fave local brand’s specific green watercolour has had some serious batch issues with this at my local art shops. Can’t get in touch with the maker as they don’t deal direct with consumers so I’ve told my art shop staff to send their duds back to make the point. I’m too old for social media even if I thought the potential for social media pile on was a good idea for this local family-made-and-owned company right now…

Hi Max. I had no idea that watercolours could glow in UV! I have a UV torch (for checking landing patterns on flower petals, as well as the cat pee scenario so so discreeetly mention) so will shine it over my paint box (and paintings!) and see what gives! Super-cool. The glowing platypus research is recent, isn’t it? I knew about scorpions, when I vouluteered at the invertebrate house in DC they had a case of scorpions in UV light. Very cool. Yeah, I know what you mean about the “shaming” thing on social media. Its a pity the local company aren’t talking to you about the green paints, you’ve got on-the-ground experience of complaints that should be really valuable to them, Idve thought.