Trees: Yew

Trees: Yew is another blog inspired by my illustrations for The Tree Forager by Adele Nozedar, published by Watkins. The book has inspired me to think about some of my favourite trees. The Yew tree Taxus baccata is the seventh in this series, along side the Sycamore, Ash, Hawthorn, Rowan, Elder and the Oak.

The Yew tree Taxus baccata is a common tree in Britain, especially in graveyards and hedgerows.

There’s a lot of folklore associated with this species, and it’s important both in modern medicine and for wildlife.

Identification: Tree shape

Yew trees grow up to 20m tall with a spread of up to 10m, and can form trees or shrubs. Their shape is highly variable because of the growth habit of the tree. In many cases, Yew loses the heartwood from the tree trunk as it ages, leaving a hollow tube full of powdery rotten wood. These trees grow incredibly slowly and are notorious for being extremely long-lived.

This makes an excellent substrate for new yew trees to grow in. New trees grow from exploratory rootlets sent out by of the established Yew. It’s common to see a younger Yew growing inside the “nursery” of an older mother Yew tree trunk. As a result of this, establishing exact ages of Yew trees can be really tricky as they rarely have the heartwood needed to count annual tree ring growth.

However, dendrologists have found yews 1,500 years old, and many believe it’s perfect possible that some trees can be up to 3,ooo years old. Quite an amazing thought.

Yew tree Taxus baccata

Often found growing in churchyards, yew trees are also used as hedging plants. They grows happily in the shadow of other trees, and frequently appear in the understory of mixed woodland. It is found planted in formal gardens. They thrive on chalky soils and are resistant to pollution.

The association with churchyards is several-fold. First, yews were used for weapons, so it was a good idea to have yew trees around. But why the graveyard? Well, yew is poisonous to grazing livestock as well as to man. Having yew in a churchyard guaranteed people wouldn’t graze their flocks on consecrated ground, but still allowed the trees to be grown.

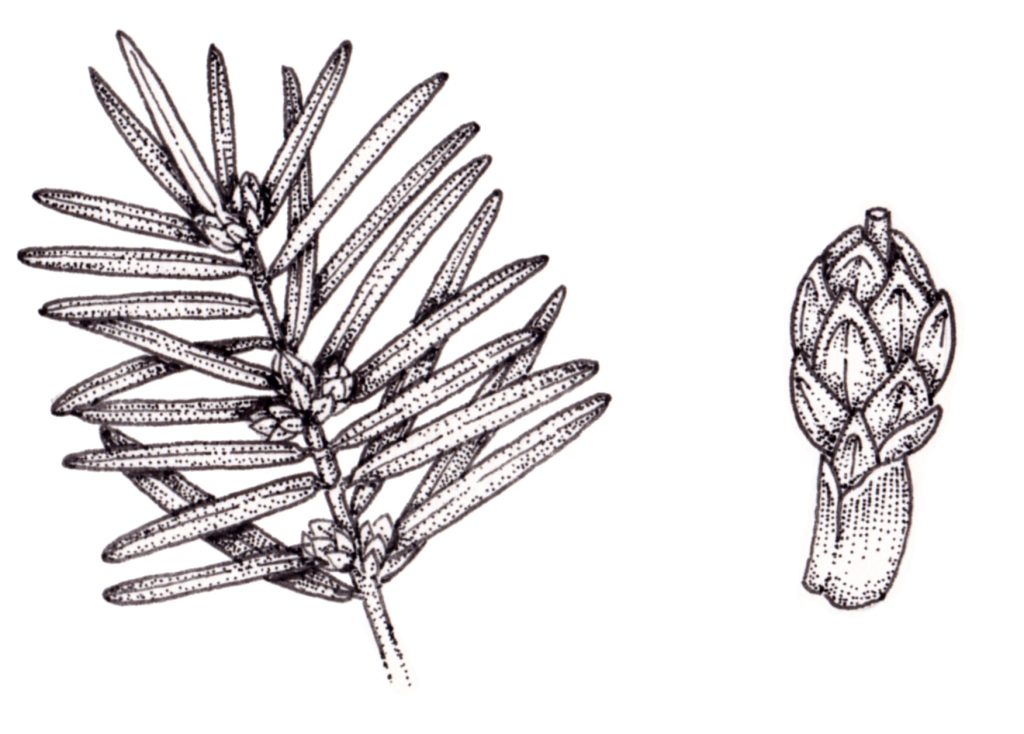

Identification: Leaves

The leaves of Yew are evergreen, so are found on the tree year round. Yew leaves are flattened dark green needles, arranged along the branches and twigs in two rows, or spiralling. Each one is 1 -3cm long. They have a sharpened tip, and may look slightly shiny. You can see a central rib on the leaves, which is especially clear on the underside. The leaf underside is a pale greyish-green colour. Needles are not arranged directly opposite one another.

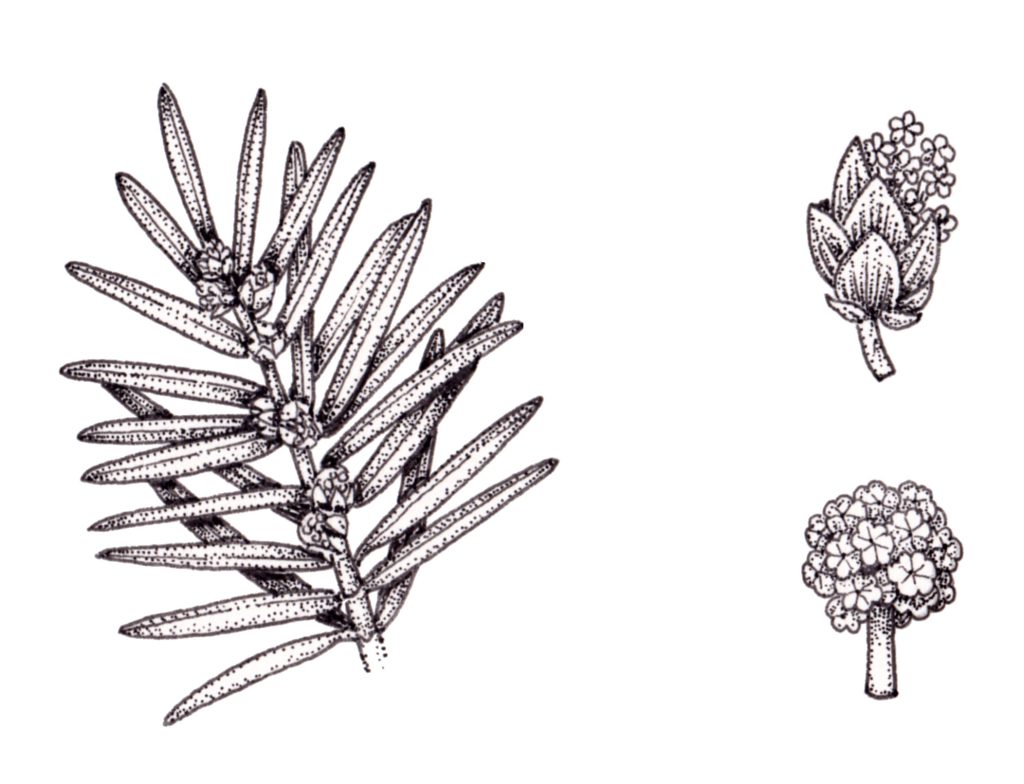

Sprig of Yew showing dark green needles with paler undersides

Like all of this tree (except the red fleshy part of the fruit), Yew leaves are highly toxic. As little as 50 – 100g of chopped yew leaves can kill an adult human .

Identification: Flowers

Yew trees are dioceious, meaning trees are male or female, each bearing male or female flowers.

You may not notice yew flowers as they are small and inconspicuous. This is because they are wind pollinated, so have no need to expend energy of showy petals and nectar treats for possible pollinators.

The flowers are in the joins between the leaves and the stem. In males, the flowers are clustered together, Female flowers are borne singly or in pairs. Each flower is tiny, males as little as 3mm. Pollen is released in February by all flowers, and berries appear in late summer.

Male flowers are round and green, with many stamens.

Sprig of yew with male flowers and a close up of the Male Yew flower. Detail below shows the froth of stamens

Female flowers are also greenish, although they become brown with age. They’re scaly, although interestingly they are not cones. This distinction is a conundrum for botanists as the yew is classed as a Conifer, which literally translates as “cone bearer”. But no cones are produced by this tree.

Each female flower has a single ovule at the centre of these scales, awhich (once fertilized) will develop into a red fruit

Female Yew flower showing scales and emergent pistil

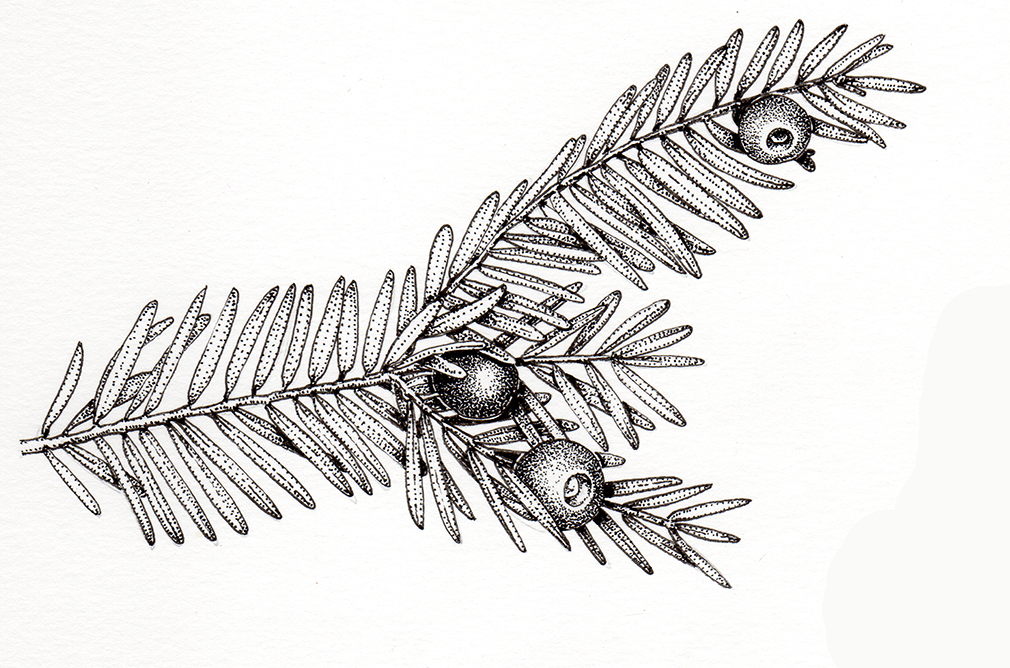

Identification: Fruit

The yew berry isn’t a true berry, but a seed that grows within an aril. These “berries” are instantly recognizable. They’re a pinkish red, matt, and fleshy. Although this fleshy aril is the only part of the yew which isn’t highly toxic, I’d advise against eating it. not least because the seed within is the MOST toxic part of the tree!

These are actually highly modified cones which grow around the seed. you can see the lone seed peeping out from one end of the cup of the aril.

Berries are 3 – 7 mm long and become ripe from October, many staying on the tree through the winter. Because of this, they’re a valuable winter food source for wildlife.

Yew berry showing seed at centre of the red aril

Identification: Bark

The bark of the Yew is scaly and a light red brown, or sometimes appears purplish. Where it flakes off, it shows redder areas below. When wet, the bark can look almost blood red.

Branches and larger twigs are also a reddish brown, although the most recently grown needles are borne on yellow-green stems. These become brown over time, normally in 3 to 4 years.

Another trait of the Yew that rather confuses its’ classification as a conifer is that is has no resin. Pines, spruce, and Firs are all resinous, a fact you’ll know if you’ve ever got the sticky gum on your hands whilst collecting pine cones.

Similar species

The only species you might confuse with the Yew is other Yew species, such as the Irish yew. This differs in having curved needles. A range of species of yew are planted in gardens, but most in the wild will be the Common or European Yew Taxus baccata.

You can tell a yew from other conifers because of the purplish-brown bark, green young shoots, and (of course) the red berry-like structures. Yew needles often appear a darker and glossier green than many other conifers.

History: Folklore

Yews are ubiquitous in folklore across geography and religions. Ancient Greeks associated them with the dead, seeing them as gate keepers to the other side. They believed if you fell asleep under a Yew you were likely to die (this was first mentioned by the physician Dioscorides in 77AD).

Pre-Christian religions held the Yew in high esteem as a tree symbolizing immortality, and groves of Yew were sacred sites long before Christians began building churches in Britain. In fact, early Christians chose to build churches near sacred Yews and thus tapped into the spirituality and respect that already existed.

In 10th century Wales, the fine for chopping down a Yew tree was £1. This becomes far more impressive when you realise that £1 was the equivalent of a life-time’s wages.

Yews figured in funeral arrangements. Processions would carry yew branches, and throw them in the grave before lowering the coffin into the earth. It was also used in graves of plague victims, although no-one seems sure why. There’s a suggestion Yew may have been seen as a way to protect and purify the dead.

However, the Yew’s association with death was never fearful. It knit closely to the way the tree seemed to live eternally, and with themes of resurrection and immortality. These traits carried neatly from pagan to Christian religion, and the yew is associated both with Easter (Jesus’s resurrection) and with the virgin Mary (eternal goddess figure).

There is also some suggestion that the ancient Norse tree of life, Yggdrasil, may have been a Yew not an Ash.

History: Mankind and Yew wood

The sheer scale of time that has seen mankind associating with Yew trees is worth a mention. This may be due to the spiritual properties associated with tree, but also relates to the incredibly tough wood the tree produces.

The oldest man-made artefact ever found is a spear made of yew-wood carved to a deadly sharp point. This extraordinary item is dated at 420, 000 years old, thus pre-dating the evolution of modern Homo sapiens. Just stop for a moment to take that date on board. It blows my mind, not least because the wood was still perfectly recognizable when discovered. (For more, see The Clacton Spear).

The Clacton spear, made of Yew and dating back more than 420,000 years

Another remarkable discovery was a bow carried by Ötzi. Ötzi is a mummified corpse found in the Tyrolean alps, between Austria and Italy. He dates back 3,500 years and has been massively important in helping archeologists figure out how people lived (and died). His bow was made of yew and was both strong and flexible.

History: Food and Medicine

Never eat Yew. As mentioned before, it’s highly toxic. And although the fleshy red aril is theoretically edible, even this has been known to cause vomiting.

However, in recent times, Paclitaxal (formerly Taxol), a compoud derived from the pacific Yew, has proved remarkably effective in the treatment of cancer. It’s a component of chemotherapy treatment for lung, breast, ovarian cancer and Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Me doing a pencil drawing of a Yew sprig

In earlier times, people knew about the toxicity of yew and it was used as a suicide drug. The chief of the Eburones, Cativolcus, chose to take yew rather than to yield to the Roman army, as did the Cantabrian and Astures armies (Redzet). It’s the taxane alkaloids that prove so toxic, and yew poisoning results in breathlessness, fever, convulsions, and eventual heart attack.

Uses

Yew is a very slow growing and fine grained wood, with a rosy red colour. It polishes beautifully and is waterproof, incredibly strong, and elastic.

The wood was used to make bows through history, like Otzi’s. Bows used at the battle of Agincourt were Yew. It’s also good for tool handles.

Waterproof qualities mean it was used for the pilings in Venice as it was resistant to rotting. Recently, when old yew pilings were removed, they were in brilliant condition despite having been submerged for hundreds of years. In many cases, they were sold on as usable reclaimed timber. (Hageneder).

Hedges can be made from yew as it grows thickly, forming good barriers. Most mazes are made from yew (including the iconic Hampton Court palace maze), which will form a good wall in about seven years.

Yews and Wildlife

The sweet, glutinous berries of yew are much prized by members of the thrush family. Blackbirds, fieldfare, thrushes as well as other birds like greenfinch glut on them in autumn. The berries stay on the tree through winter, making this a valuable resource.

Small birds such as fire-crest and goldcrest make their nests in the thickets of yew hedges. And small mammals like dormice and squirrels will also feast on the sweet berries. (Please note that the dormouse pictured below is not eating yew.)

Hazel dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius

Yew is the foodplant of the Satin beauty moth, Deileptenia ribeata.

Threats

Threats to the Yew tree are limited. However, climate change may cause problems, and is is susceptible to root rot. A while back, the Yew was over-harvested for Taxol medicines. Thankfully this is now manufactured in the lab.

Conclusion

The Yew is an important tree in the landscape and in human experience. Drenched in pre-history and spiritual associations, it also bears amazingly strong wood, and has helped with potentially life-saving cancer drugs. It’s also unusual. It’s a conifer but not quite a conifer. It is somehow immortal because of its growth habit. It’s highly toxic yet the source of life-saving medicines. Associated with graveyards and funerals, it also symbolises resurrection. It’s these peculiarities that make the Yew stand out, and earn it’s place as one of the most interesting of British trees.

Online sources for this blog include websites of The Woodland Trust, Tree guide UK, Trees for life, and Naturespot. Reference books for this blog include the excellent The Greenwood Trees by Christina Hart-Davies , and the Reader’s Digest The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain (out of print but commonly available second-hand). I also referred to The Tree Forager by Adele Nozedar and The Living Wisdom of Trees by Fred Hageneder.

I’ve published a film on youtube to accompany this blog. It shows me drawing a pencil line illustration of a sprig on yew from a specimen, and was made in response to requests for films showing me drawing and composing an illustration, not just painting botanical subjects.

Hi Lizzie, wonderful and informative as usual. Hope all is well there.

Regards Peter

Thanks so much Peter, things all good here. Plenty of work but not too much, and sparrows in amongst the wild flowers I can see from my studio window.

I acknowledge the toxicity of yew. The foliage is poisonous even when dry and people were supposedly poisoned by produce stored in yew barrels but I think your concernsl about the aril flesh is unfounded – I’ve even made wine out if it.

It’s believed there is a mild toxin in the fruit. Studies of birds visiting yew, found birds of difference species limited the amount of fruits they swallowed. And drank profusely afterwards. Some birds, hawfinch, greenfinch,demolish the seed swallowing it. Others swallow the extremly hard seed whole & it passes through the digestive system. Even the gizzards of large birds & stomachs of badgers. Other birds seperate the seed from the fruit & discard it before swallowing the fruit. Evidence is fruit pulp found on walls and branches.Why a wide range of animals feed on yew (berries and leaves) and yet are apparently unaffected by the toxins is little understood.

Hi Bill

This is completely fascinating, I had no idea. I know some animals eat yew, but the nuances of it are really interesting. Thank you for sharing your knowledge.

Some critics of the Trump administration are questioning 옥천출장콜걸Trump’s motivation to send the money to Qatar.