Trees: Beech

Introduction

Beech trees are common across Britain, favouring chalky soils. The oldest Beech trees live up to 400 years. You’ll find them in open spaces and in woodland and can tell them straight away by their smooth bark. The trees produce beech mast which is nutritious for animals, and the canopy supports wildlife. Beech wood is used in furniture making, and has links to the earliest of books. It’s associated with knowledge and femininity, and has been used to treat ailments and as food.

This is one of a series of blogs I’m writing on common British trees. You can also see blogs on the Elder, the Yew, the Ash, the Oak, the Holly, the Sycamore, the Rowan, and the Hawthorn.

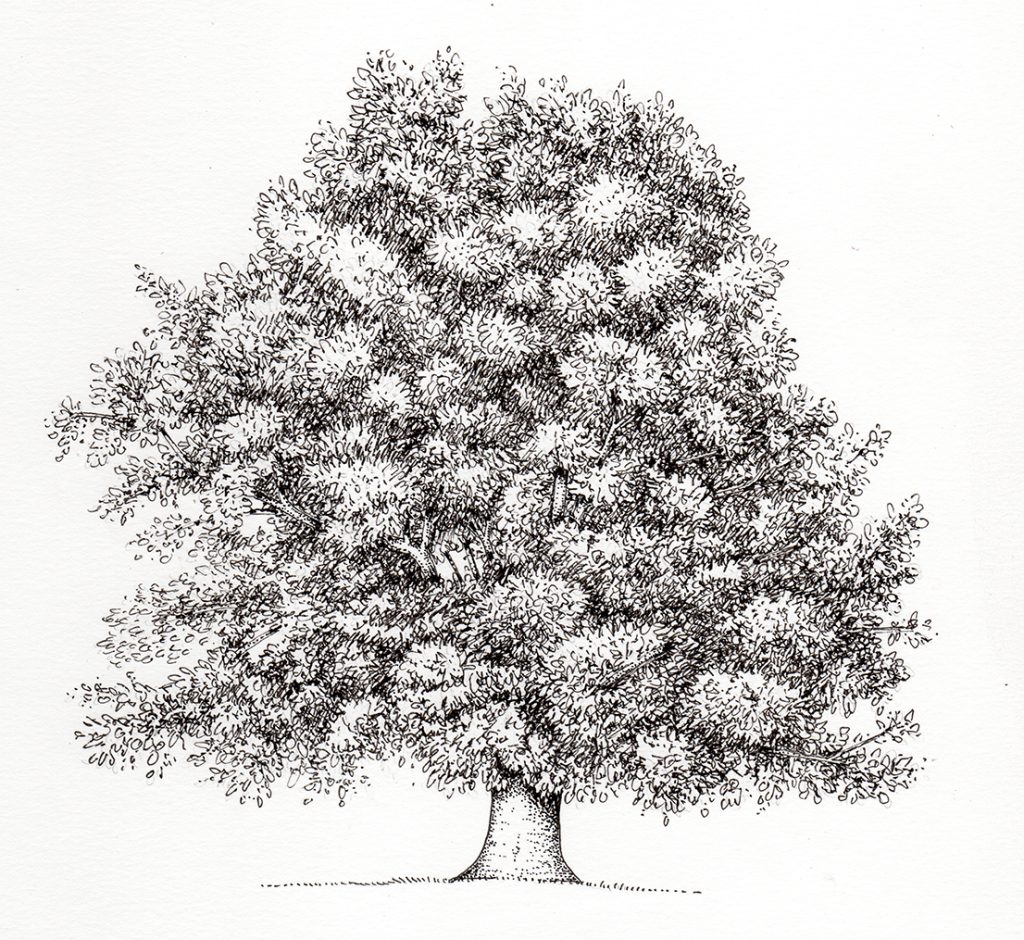

Identification: Tree shape

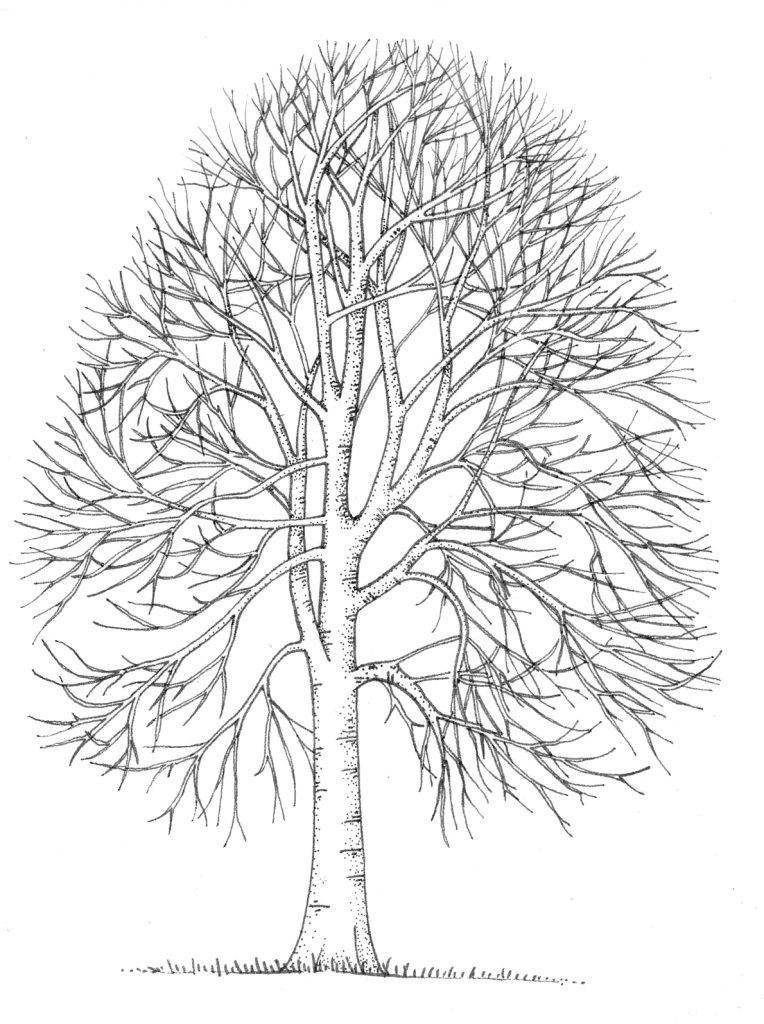

The Beech grows up to 30m tall, and its’ shape varies according to where it’s growing. In open fields, the branches spread into a wide canopy. In confined woodland there are few side branches and a much straighter silhouette.

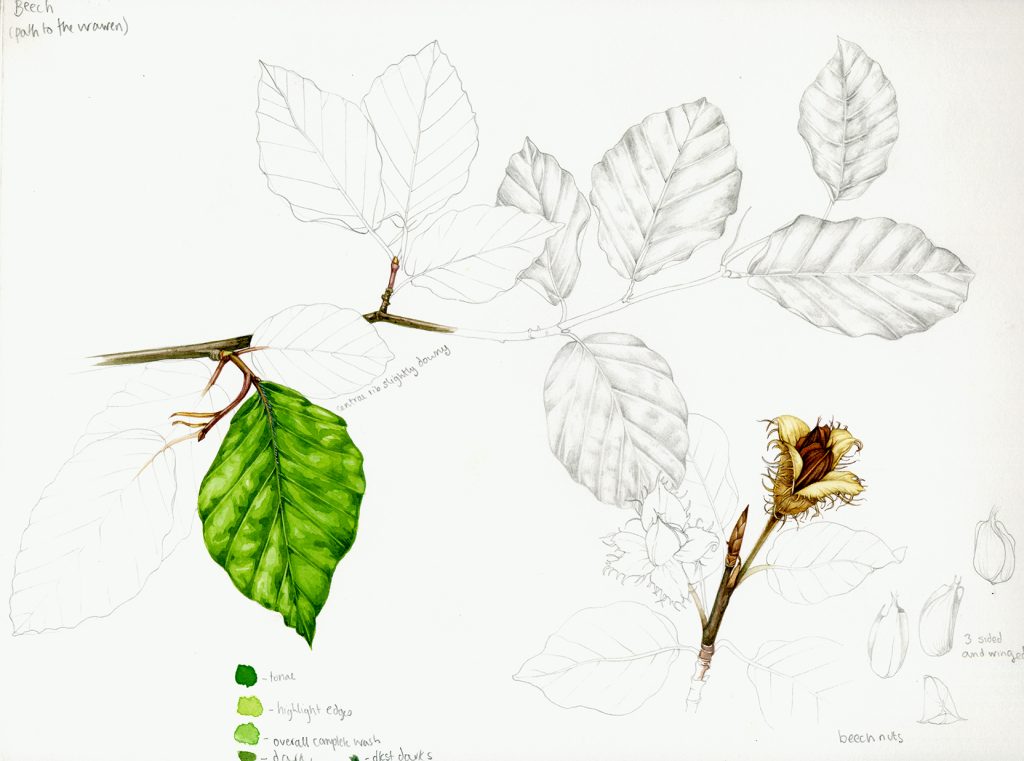

Identification: Leaves

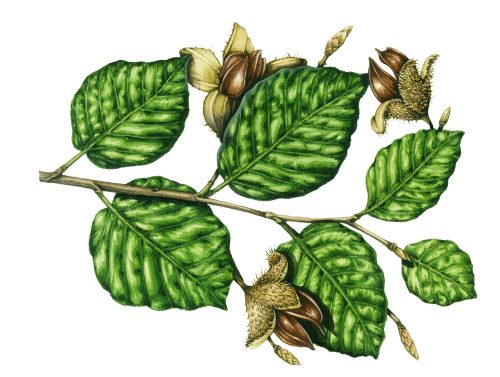

In spring, as they unfurl, Beech leaves are a bright acid green, and are covered in downy hairs. As they mature they become a more modest green, and in autumn have a pretty consistent warm tan colour. Leaves are 4 to 9cm long, and are oval with smooth but wavy margins. They’re arranged alternately. Each leaf has 5 to 9 pairs of veins.

Leaves overlap, making an umbrella-like canopy with shields the floor below from rain. They also are rich in lignin, which means they decompose slowly. This means the woodland floor is often a difficult habitat, dry and carpeted with persistent crunchy leaves. You could know you’re in a beech wood by sound alone.

Beech trees hang onto their leaves through winter, which is known as macrescence.

Be aware that the common Copper beech is a varient of this native species. It looks similar, but the leaves are a dark maroon instead of green.

Identification: Flowers

Male and female flowers are carried on the same plant, and are pollinated by the wind. Female flowers grow in pairs, within a little cup. Male flowers are catkins carried on long, tassel-like catkins. Flowers appear as the young leave emerge in spring.

Identification: Fruit

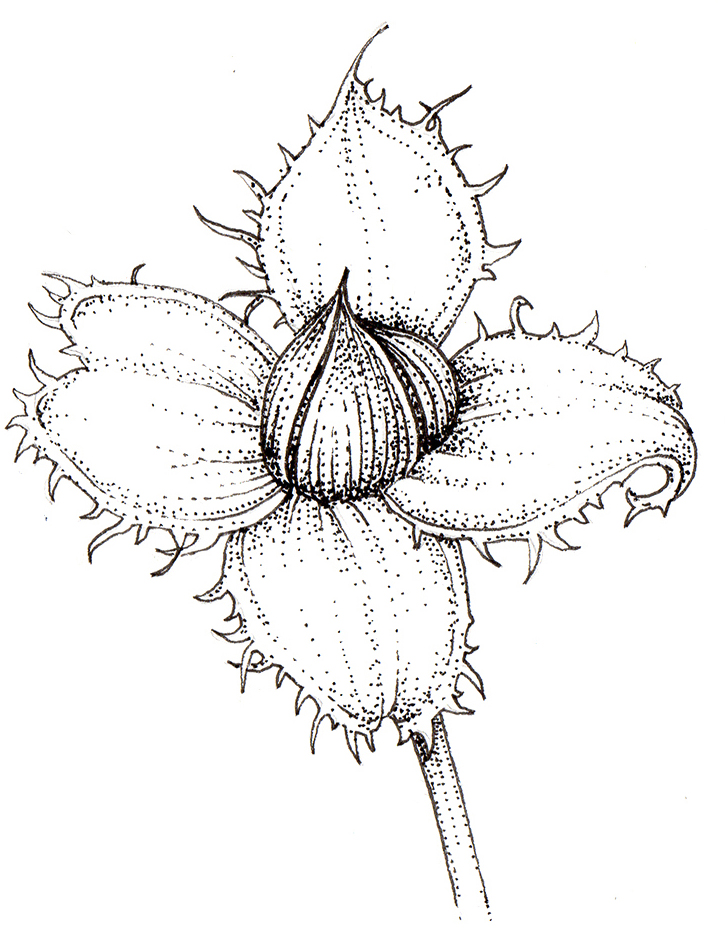

Beech nuts are known as mast, and consist of three triangular nuts encased in a spiny case. This splits open, revealing the chestnut-brown nuts surrounded by a pale velvety lining.

They’re produced in real abundance once every four or five years, which is known as a mast year.

Identification: Bark and buds

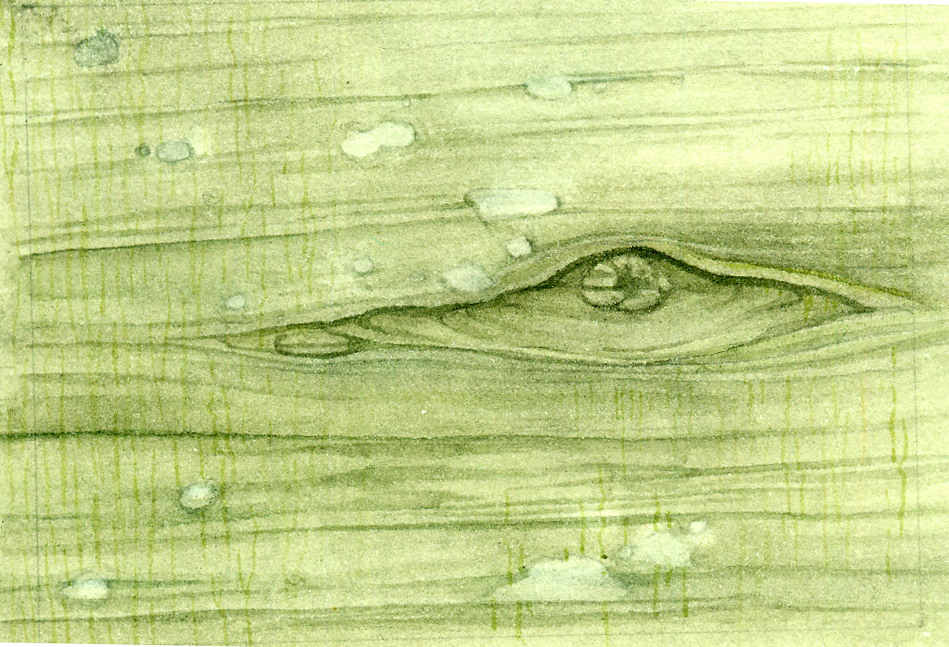

Beech bark is really distinctive. It’s very smooth and pale grey. It stretches as it grows, so when names are carved on beech trees they become distorted over time.

The bark is sensitive to sunlight. If an older tree is suddenly exposed to a lot of direct sun, the bark will get “sunburn” and this can kill the whole tree.

Buds are distinctively pointed and slender, reddish brown and with a clear criss-cross pattern. No other trees in Britain have quite such pointy buds, which (along with the bark) means it’s easy to identify in winter.

Similar species

Because of the smooth bark and persistent leaves, beech isn’t readily confused with other trees. Hornbeam Carpinus betulus has similar shaped wavy leaves, but these have teeth on the margins

History: Folklore

Beech trees have been associated with knowledge and femininity. In Britain, the Beech is sometimes called “the queen of the woods”. Romans had sacred beech groves, some dedicated to Jupiter, and some to Diana, Goddess of animals and the hunt.

Writing and learning have associations with the Beech, possibly because of its links to the invention of the book.

In Westphalia, in Germany, up til the 18th century there was a tale that babies weren’t brought by the stork, but found in the hollows of Beech trees.

Finally, druids often used beech twigs for water divination.

History: Mankind and Beech wood

The wood of beech is hard and heavy, but not tough. It’s no good for building as it can’t bear weight, but responds well to steaming so has been used to make the backs and legs of Windsor chairs and other bentwood furniture. Trees were often pollarded for this purpose.

The wood burns hot, and was used in industry – fuelling fires for iron, glass, and charcoal production.

Beech mast is over 50% oil, so the nuts have been used as a source of furniture polish. Meanwhile the leaves, non-degrading and persistent were used to stuff (presumably very noisy!) mattresses.

Beech tar was used as glue from paleo to mesolithinc times.

Before the invention of paper, thin slabs of beech wood were used to write on, and sometimes bound into prototype books. There’s evidence of this in Germany in the 1300s. There’s some suggestion that Guttenburg had the idea for his historic press after writing on beech wood and noticing the pressure made a print on the page below.

History: Food and Medicine

The beech mast is highly nutritious, providing oil and protein, but is very difficult to access. In general, it was fed to cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep who foraged in woodland, or gathered up and fed to overwintering livestock.

However, in times of hardship, and until the Iron age, beech mast was roasted and made into flour. In France, the roast mast was used to make a coffee-like drink.

Newly emergent leaves are tender and can be used in salads and soups.

Beechwood tar was used as chewing gum, and I’m sure even in my childhood in the 1970s you could buy packets of Beech nut chewing gum,

Medicinally, Beech was used to treat bronchitis and has astringent, antiseptic and disinfectant properties. These were recognized by early Europeans and by the First Nations People in the Americas, who used bark preparations to fight fever.

It’s also used to treat animal hoof ailments, and in soap production.

Beech and Wildlife

The unusually shady forest floor found in beech woodland initially seems devoid of life. However, some rare plants like the Coralroot bittercress and Red helleborine love these conditions, as do fungi.

Truffles can grow here, and in the past beech woods were planted to encourage them.

Moths feed on the leaves, namely the Olive Cresent, Barred Hook-tip, and Clay triple-line species.

Wood boring insects and larger animals like woodpeckers often make their homes within the tree.

The beech mast feeds a whole ecosystem; from voles to badgers, squirrels to jays, mice to great tits, woodpeckers to nuthatches.

Threats

When compared to other British tree species, the Beech isn’t in too much trouble.

At around 200 years old they can develop core rot in they’re growing in an environment low in tannic acid. Basically, this means anywhere without Oak trees growing nearby. This can kill them.

The trees can suffer root rot, caused by fungus like Phytopora,

Beech bark disease is caused by scale insects and a canker fungus. This causes lesions to appear on the bark every year. Eventually, these encircle the tree and thus can kill it.

However, a swifter way for a Beech to be “girdled” is when Grey squirrels come and strip all the bark off. This can soon result in death and is especially problematic in younger trees.

Conclusion

The Beech tree is common, easy to spot, and useful. With the smooth bark, pointy buds, and over-wintering orange-ish leaves, it’s easy to identify. Although not used in building or as food; the wood and beech mast has proved vital over the centuries. From chair backs to chewing gum, charcoal production to ancient flour, livestock feed to books, fevers to ancient glue; the Beech tree has served mankind well.

They’re pretty trees, and well worth a closer look next time you’re in a woodland with crunchy leaves underfoot.

Online sources for this blog include websites of The Woodland Trust, Kew’s Plants of the World, Tree guide UK, Trees for life, and Naturespot. Reference books for this blog include the excellent The Greenwood Trees by Christina Hart-Davies , and the Reader’s Digest The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain (out of print but commonly available second-hand). I also referred to The Tree Forager by Adele Nozedar and The Living Wisdom of Trees by Fred Hageneder.

A really lovely article, thank you. Informative and interesting, beautifully illustrated.

Thanks Christine, really glad you enjoyed it

Dear Lizzie, Thank you so much for this in-depth lesson on drawing and painting beech trees – including origins and history. I grew up in a home in the Chiltern Hills surrounded by beech trees. At the time, they were everyday life but now that I live in Australia, I miss them a lot (although I love eucalypts!)

I attend pottery classes and am trying to re-present the beech trees and beech woods of my childhood in one symbolic project.

This lesson which you have so kindly given is encouraging me to consider learning to illustrate botanicals, thank you.

Hi Helena

How interesting, learning to transfer your love for Beech trees to love for Eucfylyptus. Isnt it odd how the landscapes we grow up with remain an integral of our definition of “home”, even decades later? Your pottery project sounds lovely, so many directions you could take it. Personally, Im terrifed of 3D and full of admiration for anyone who can take on that extra dimension! Yes, if you are creative, as you clearly are, then do give illustrations a go. Maybe start simple with line drawings, and see how you enjoy it. And dont get too hung up on botanical perfection! Thanks so much for your comments, transported me to a Chiltern beech wood in autumn, which is a great way to start any day.