Trees: English Oak

I’ve been working on illustrations for “The Tree Forager” by Adele Nozedar, due to be published in August 2021. It’s inspired me to have a look at a few of my favourite trees. The English oak is the first in the series.

The English oak Quercus robur truly is an iconic tree. English Oak is also known as the Common oak, and the Pedunculate oak. Across the fields of Britain, lone oaks stand in meadows, and form thick woodlands rustling with wildlife. Oaks produce hard-wearing timber. They are thoroughly bound up in religion, folklore, and mythology.

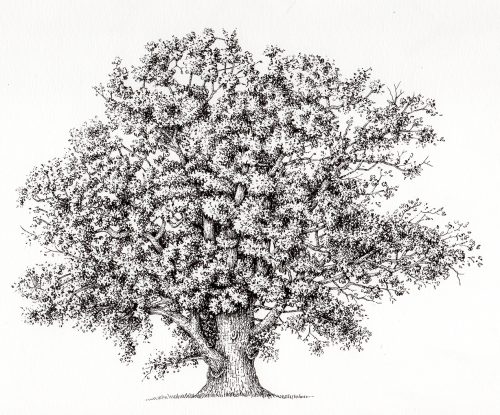

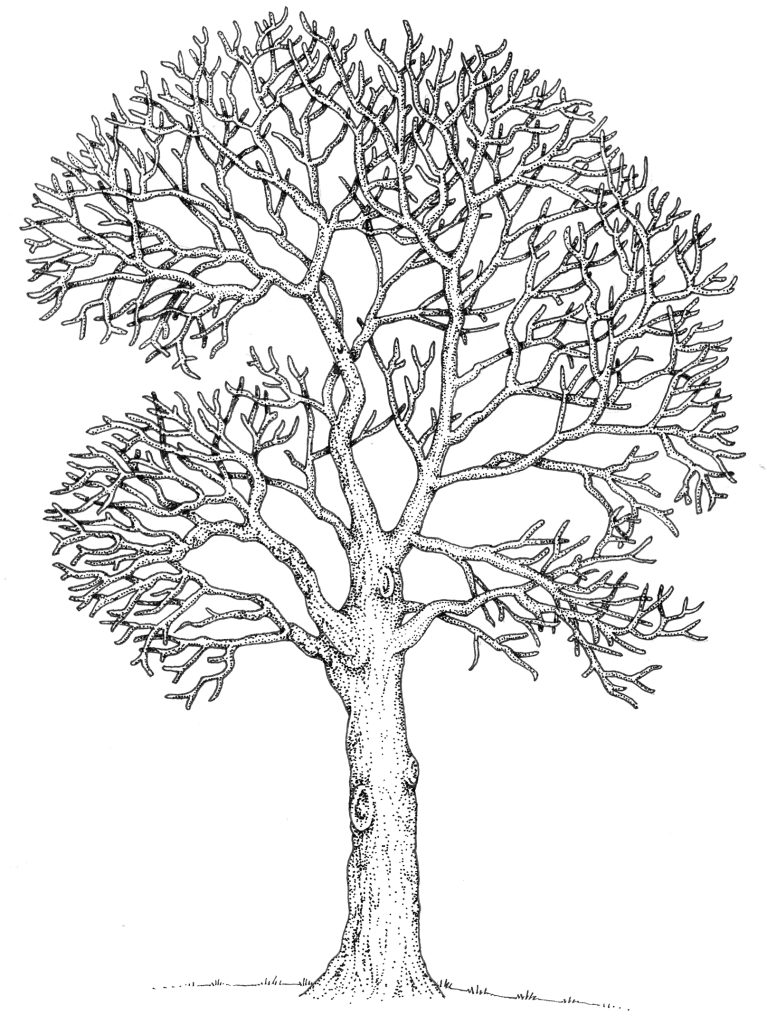

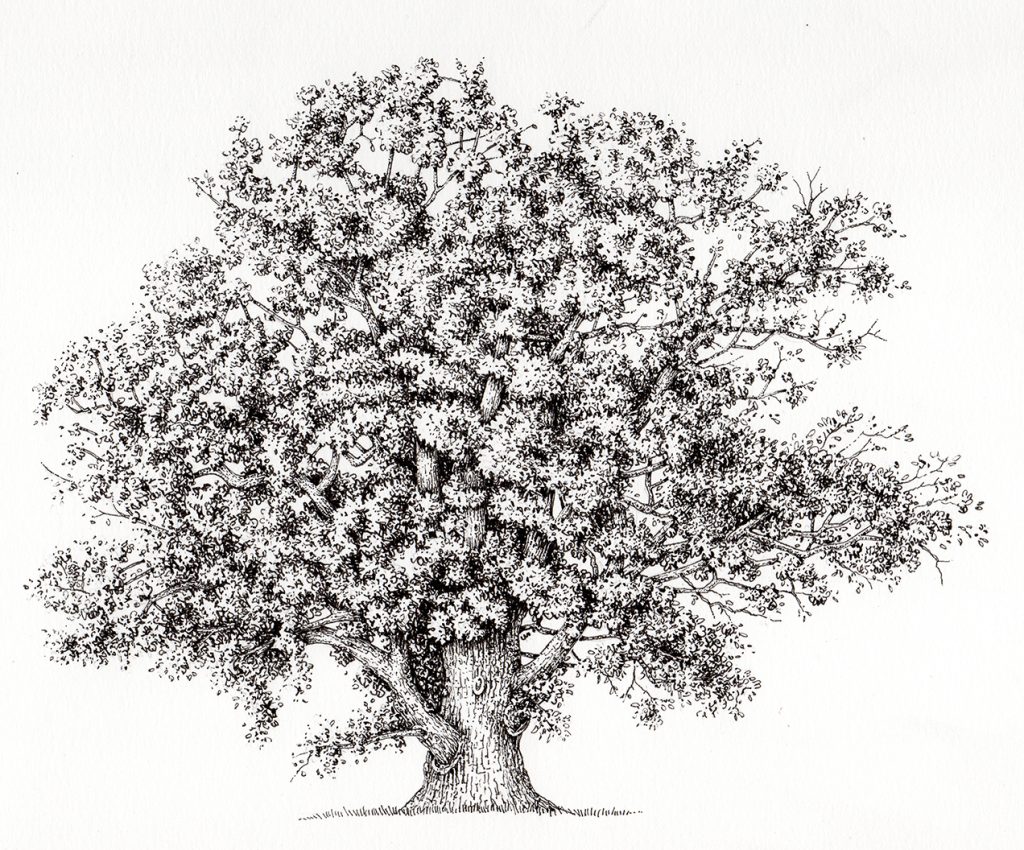

Identification: Tree shape

Oak trees are sturdy, and old trees can have a girth of up to 17m. Their large branches grown from a short trunk, with a large crown. Trees can grow to 37m tall.

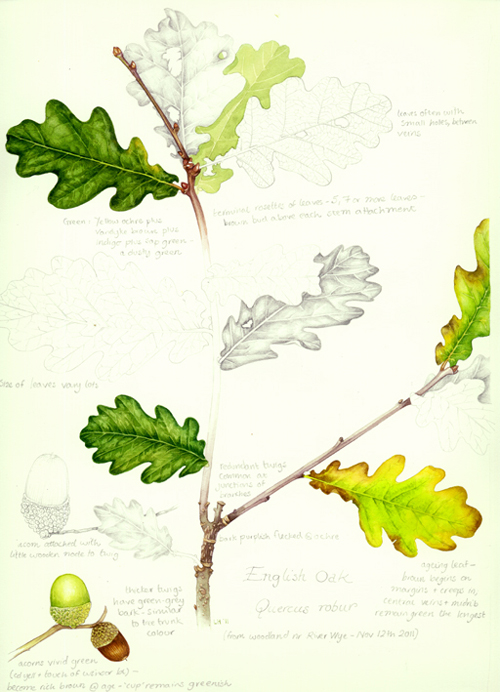

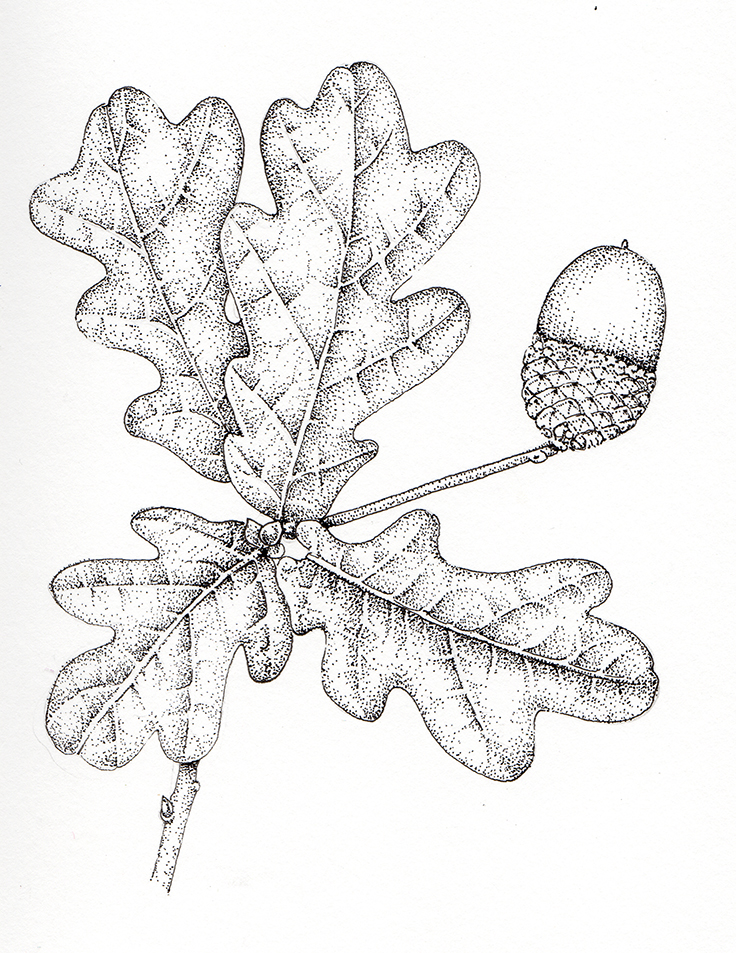

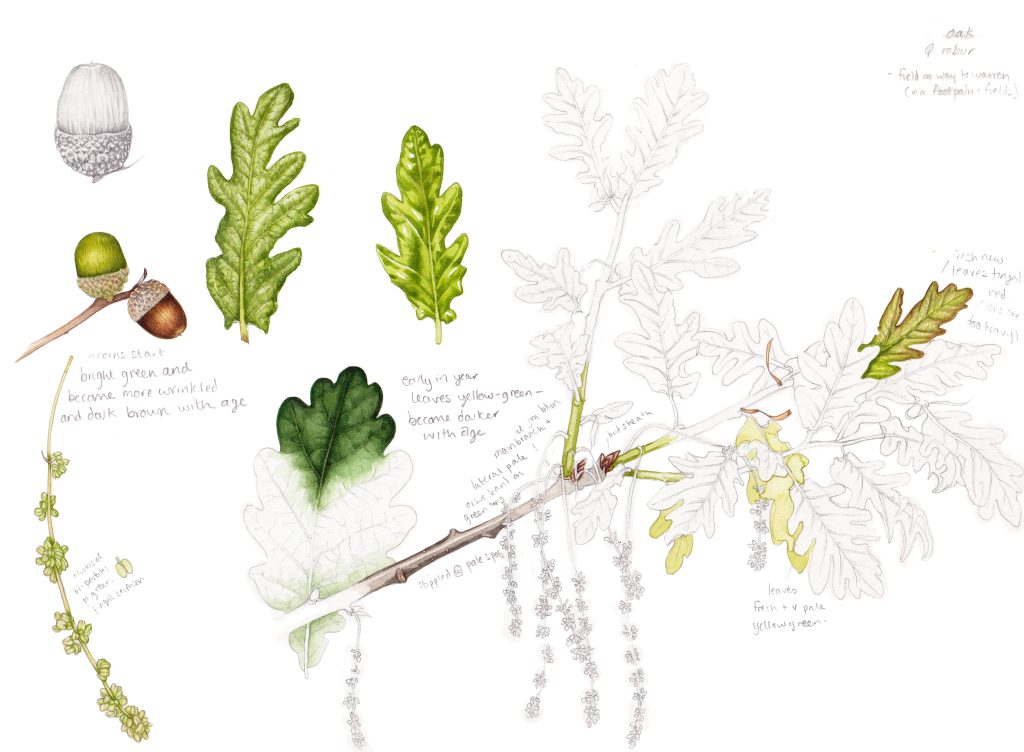

Identification: Leaves

Oak leaves are very distinctive, with 3 to 5 pairs of unequal, blunt lobes. They’re alternate, and have little or no stalk. Either side of the leaf has four or five lobes. At the base there are little flaps or “ears” which give a curved shape, known as auricles. The underside of the leaf is hairless.

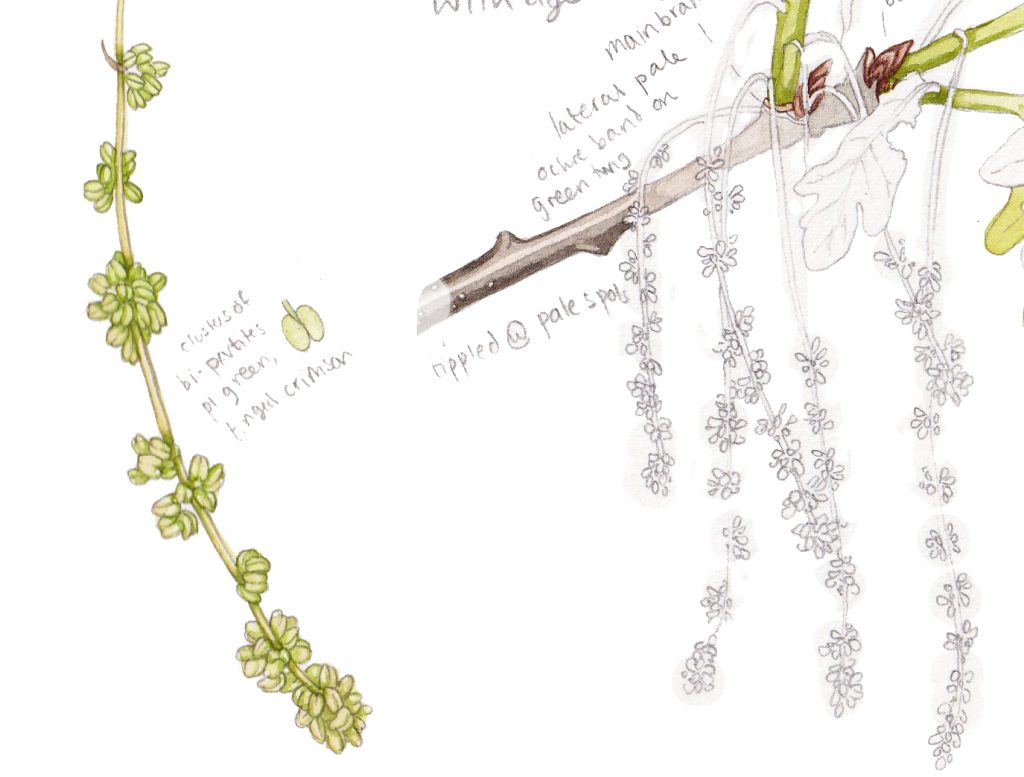

Identification: Flowers

Oak flowers are small and may well have evaded your attention. They’re yellowish green and borne in catkins. Male and female flowers are carried in different catkins. Female ones are erect and have 2 to 4 flowers, which are flushed red. These will be pollinated by the end of May and develop into acorns. Male catkins droop and consist of more blooms. Flowers are wind pollinated, hence their small size and lack of showy petals.

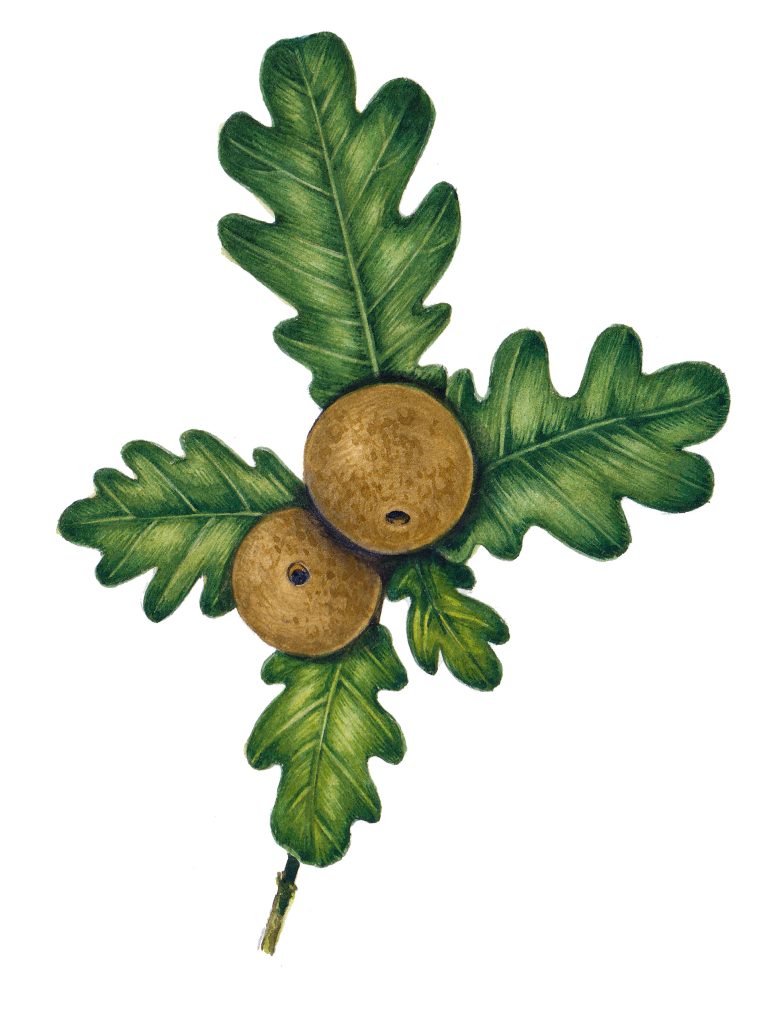

Identification: Fruit

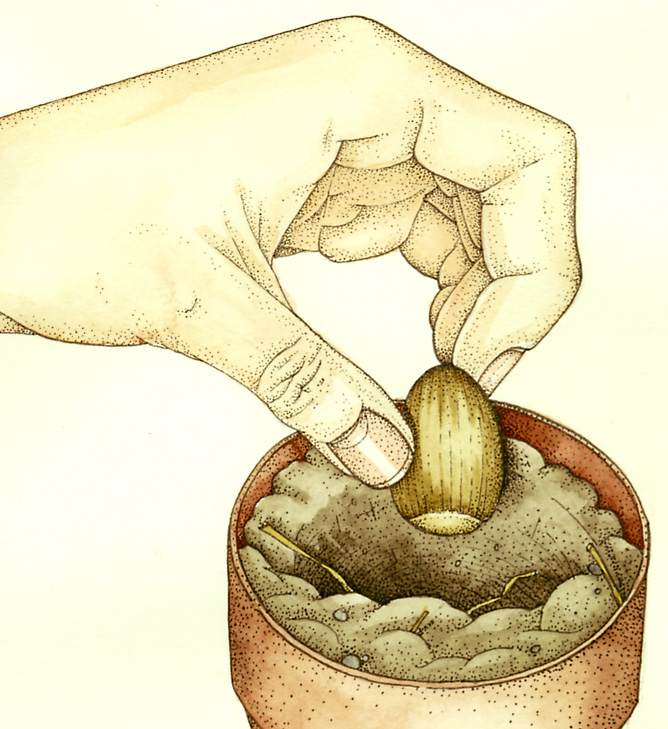

Everyone can identify an acorn. Most of us have pretended to be one when very small, growing into a large oak tree. Acorns are actually nuts surrounded by a cup-like structure known as a cupule.

They’re 2 – 2.5cm long, and grown in clusters of 1 to 4. English oak acorns are carried on long, stiff stalks. In autumn, the acorns turn from a pale bright green to brown, and fall in their masses to the ground.

Sometimes, acorns are afflicted with Knopper gall. This is caused by the tiny gall wasp Andricus quercuscalicis and cause the acorn to become twisted and distorted.

Identification: Bark

Bark starts out smooth and shiny. It becomes finely vertically fissured and cracked with age.

Similar species

There are several species of oak in the UK, but only the Sessile oak Quercus petraea shares the rounded lobes of English oak leaves. It can be told apart from the English oak in various ways.

Sessile oak leaves have flat bases, lacking the auricles of the English oak. Leaves have clear stalks, whereas the English oak leaves have almost none. Sessile oak leaves have hairs on the midrib vein on the underside of the leaf. They have 4 to 6 pairs of equal lobes. English oak leaves are glabrous below, and lobes are uneven. Sessile oak acorns have no stalk, and are shorter and fatter. The acorn of the English oak has a long stalk.

Other species of oak have spikier leaves, or leaves with less distinct lobes. These include the Scarlet oak Quercus coccinea, Red oak, Quercus borealis, and Pin oak Quercus palustris. There’s also the Lucombe oak Quercus x hispanica, Turkey oak Quercus cerris (with its’ furry acorn cups), and the Hungarian oak Quercus frainetto.

History: Building

Oak has long been used for building as it is extremely durable and strong. Shingles, beams, and steeples across Britain are built with oak. Salisbury cathedral boasts the tallest spire in England. It is supported on a lattice work of 2641 tons of thirteenth century oak beams.

Oak was used for wheel spokes, ladder rungs, and shipbuilding. Henry VIII’s warships were made from oak, much of it coppiced. It took up to 3,000 mature oaks to build one ship. Oak trees were grown into curves to supply “compass timber” for the bow and keel. In fact, during the reign of Elizabeth I, laws were passed to promote the planting of oak and to limit its felling.

Curved timbers were also used in cruck frames, called for by house builders. Half-timbered houses are built with oak frames.

The Three Tuns pub in Hay-on-wye

The high tannin content in oak bark has meant it’s been used for tanning leather for thousands of years.

History: Folklore

Vikings saw the oak as the tree of their god of thunder, Tor. It has also been dedicated to other thunder gods; Jupiter, Zeus, and Thunor. Oak is often struck by lightning which explains the connection.

Symbolising health and long life, bride grooms would carry acorns in their pockets. Couples would get married under oaks until the church banned the practise. Instead, married couples would race from the alter to the oak, and dance around it for luck. Dreaming of oak suggested good health. Christian preachers read and gave sermons under oaks. King Charles II hid in the hollow oak at Boscabel house (in the village where I grew up), to escape the parliamentarians.

History: Food & Medicine

Acorns were ground into a flour to make bread before the cultivation of wheat, and were vital provisions for pigs which roamed free in the forests.

The bark of oak was made into a gargle for sore throats, ground acorns made a snuff to treat nosebleeds. There are suggestions that oak leaves may have been used to treat diarrhea.

Oak apple galls were (and indeed still are) ground up to make a beautiful and permanent ink.

Uses

Oak is still used today for building, notably in oak panelling and furniture. Its’ hard-wearing properties make it ideal for flooring, and oak veneers are popular. Whisky barrels are still made of oak, and it’s a good choice for fence posts and firewood.

Threats

There are threats to the sturdy oak tree, alas. They get cleared when hedgerows are grubbed up and habitat is lost to development.

They also are prone to Oak sudden death, or Ramorum dieback. This is caused by the oomycete fungus Phytophthora ramorum. The disease causes bleeding, dieback, and canker. Luckily for the English oak, this disease seems to cause more death in its’ American cousins. Unfortunately for British forestry, it has spread to Japanese Larch where it is doing untold damage.

Oak are also susceptible to other diseases such as Acute Oak Decline (AOD). This leaves dark cankers and causes crown thinning and death. For more on AOD and other tree pathogens check out the Forestry Research site.

Conclusion

The English oak is such a glorious tree. Nothing beats its gnarled shape, sentinel in a field or meadow. Oak woods are an extraordinary habitat for animals ranging from insects to deer. These deciduous woodlands create space for other wild flowers to grow and thrive.

Over the centuries, oak has been used in religion and spirituality, as medicine, for ink, barrels, house building, and warships. Acorns have fed untold herds of pigs and provided bread.

This common British tree has been many things to us, and remains a glorious plant and an important iconic tree.

References for this blog include the excellent “The Greenwood Trees” by Christina Hart-Davies , and the Reader’s Digest “The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain” (out of print but commonly available second-hand) , and Collins Flower Guide by David Streeter.

very well written and informative Lizzie.

Thank you, E!

Thanks for the lesson. I should get over myself and try my hand at making ink from galls. I have certainly collected my share.

Bobbie, yess! Ground up galls make the most glorious ink colours. And I think ground up walnut makes another amazing deep brown colour. I have a friend who paints with beetroot…