Grass: An introduction

Grasses (Poaceae) are one of my favourite botanical illustration subjects. I adore drawing and painting them. I have written a blog on my passion for this family of plants before. However, I wanted to take another look at the way grasses are put together. I also want to introduce beginners to basic grass anatomy and terminology. This will help you start to understand these glorious and diverse plants.

(We should also mention the rushes and sedges. These are also monocots. For a beginners guide to sedges click here, for a beginners guide to rushes follow this link.)

Drawing a plant is one of the best ways to begin to understand it. I hope this crash course in grass anatomy will help.

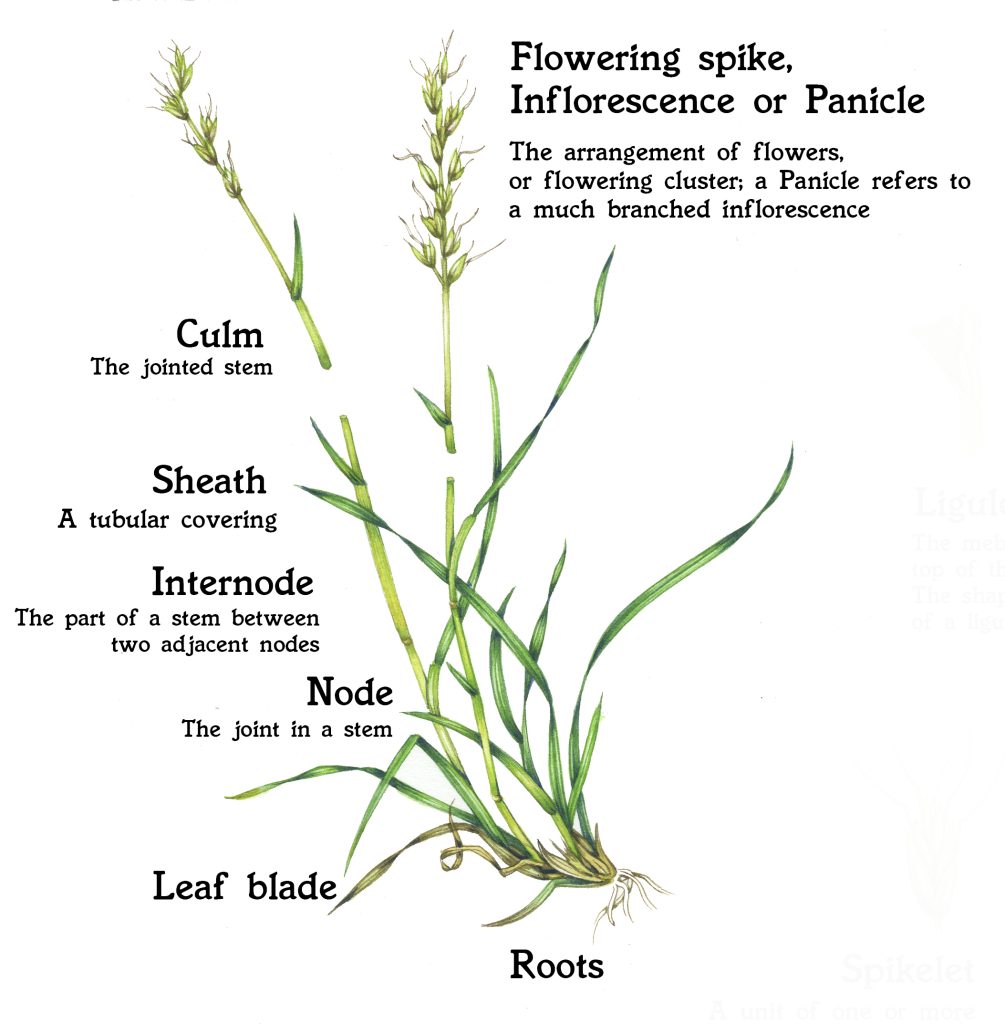

Anatomy of Grass: Overview of the Plant

Grasses have long leaves or blades, straight thin roots, a rounded (often hollow) stem (or culm), and a flowering spike. Lots of people may not realise that the top region of a grass plant happens to be the plant’s flowers and seeds. It becomes obvious when you think about a grass like wheat, but other species might fall under the radar.

Bread wheat Triticum aestivum

The culm of a grass has “knees”, these are known as nodes. These nodes might be at a bend in the culm, or just on a straight run of the stem. The culm tends to be swollen at the nodes. They may be hairy or smooth, depending on species. This bending at the nodes is known as genticulate growth. Some people confuse grasses with sedges and rushes; remember that grasses are the only one of these groups which can “bend at the knees”.

The space between these nodes is called the internode. Its length can help differentiate between species of grass.

Blades (leaves) of grass tend to be flat and linear. They are rranged alternatively up the culm, and have parallel and unbranching veins. Blades can be broad, or needle like. In some species they roll in on themselves to make bristle-like leaves. Noting if they are hairy or smooth helps determine the species.

The blades of grass grow up the culm like a tube, then grow outward. This encircling or tubular covering is known as a sheath. Sheaths may cling tight to the culm. They may be loose and inflated. This is yet another thing to look out for if you’re trying to i.d. a grass plant.

Overview of the anatomy of a grass (Meadow oat grass Avenula pratensis)

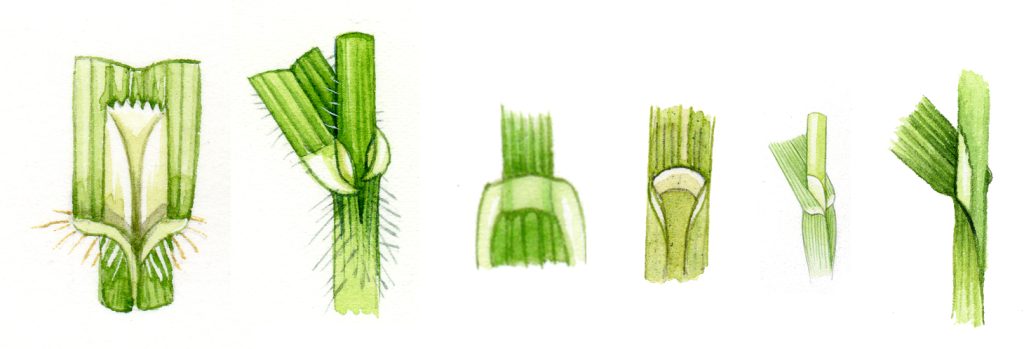

Grass Ligules

Ligules are little flaps of membranous tissue that form at the top of the sheath and the base of the leaf blade. They are very cool as their shape varies a great deal from species to species. In many cases they’re tiny, so a hand lens might be handy if you’re going to take a closer look. Some ligules are pointed, some are rough edged, some very thin, some broad and easy to spot. Some species have no ligule, or have a ligule which is reduced to a ring of hairs.

Sometimes the edges of the leaf blade cling to the culm and surround the ligule (as in the second illustration below); these structures are called auricles.

Ligule variety in different species of grasses

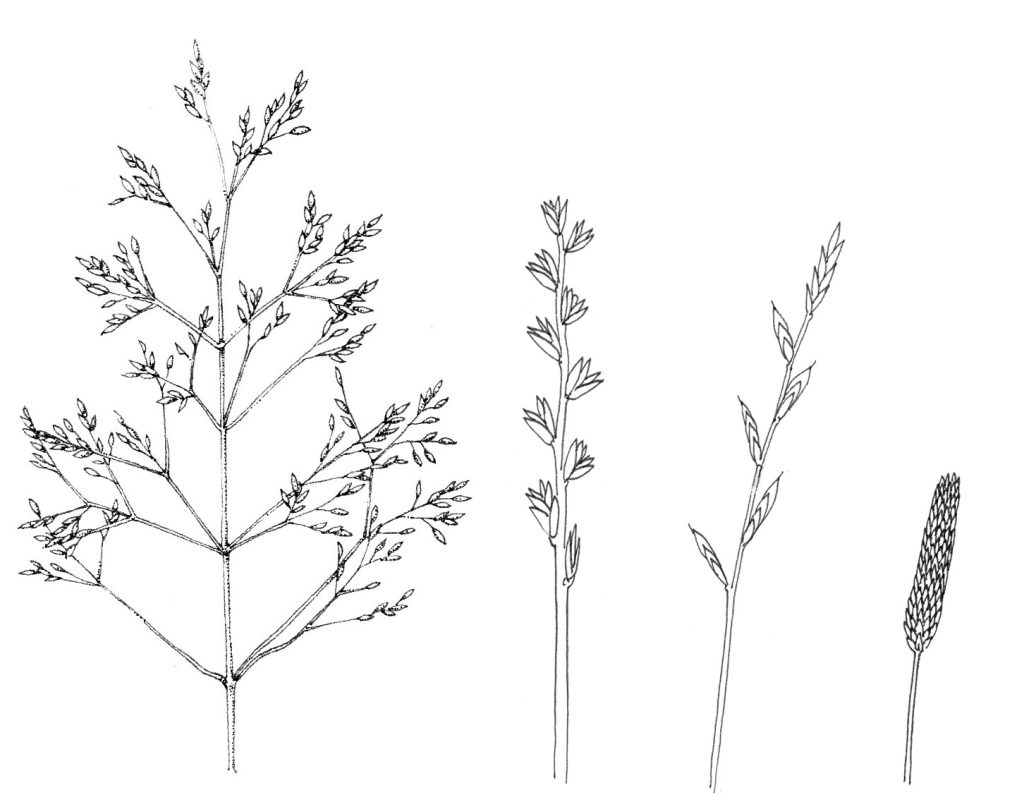

Inflorescence variety in Grasses

The flowering part of a grass plant is called the panicle, flowering spike, inflorescence or flower-head (many of these terms also apply to other families of plant, and botanists use them somewhat differently at times, which can be confusing). These flowering heads consists of lots of tiny grass flowers which are called spikelets.

Diagram showing flowering spike diversity in the Grasses family: Spreeading panicle, flowering spike, Raceme & Compact panicle

If the flowering spike is unbranched, with each individual spikelet attached to the central stem by a stem (or rachis) it’s known as a raceme (as with Rye grass Lolium perenne and Tor grass Brachypodium pinnatum).

Racemes: Tor grass Brachypodium pinnatum and Italian Rye grass Lolium multiflorum

Panicles often refer to grasses whose spikelets are borne at the end of stalks on a branching flowering head. They show an enormous amount of variety both in individual plants (depending on the age and developmental stage of the plant), within species, and (obviously) between species.

Variety of panicle shape: Yorkshire Fog Holcus lanatus showing one panicle still within the sheath, one fully spread at maturity.

Some other grass species with spreading panicles include Cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata, Common bent Agrostis capillaris, and Wavy hair grass Deschampsia flexuosa.

Spreading panicles in Cocksfoot Dactylis glomerata, Common bent Agrostis capillaris, and Wavy hair grass Deschampsia flexuosa

Panicles can also be very compact, and look like one tight structure. This is particularly true of the Meadow foxtail Alopecurus pratensis.

Tight panicle shown by Meadow foxtail Alopecurus pratensis

Some other grasses with tight panicles include Crested Dog’s tail Cynosurus cristatus, Twitch grass Alopecurus myosuroides, and the Foxtails.

Tight panicles shown by Crested Dog’s tail Cynosurus cristatus, Twitch grass Alopecurus myosuroides

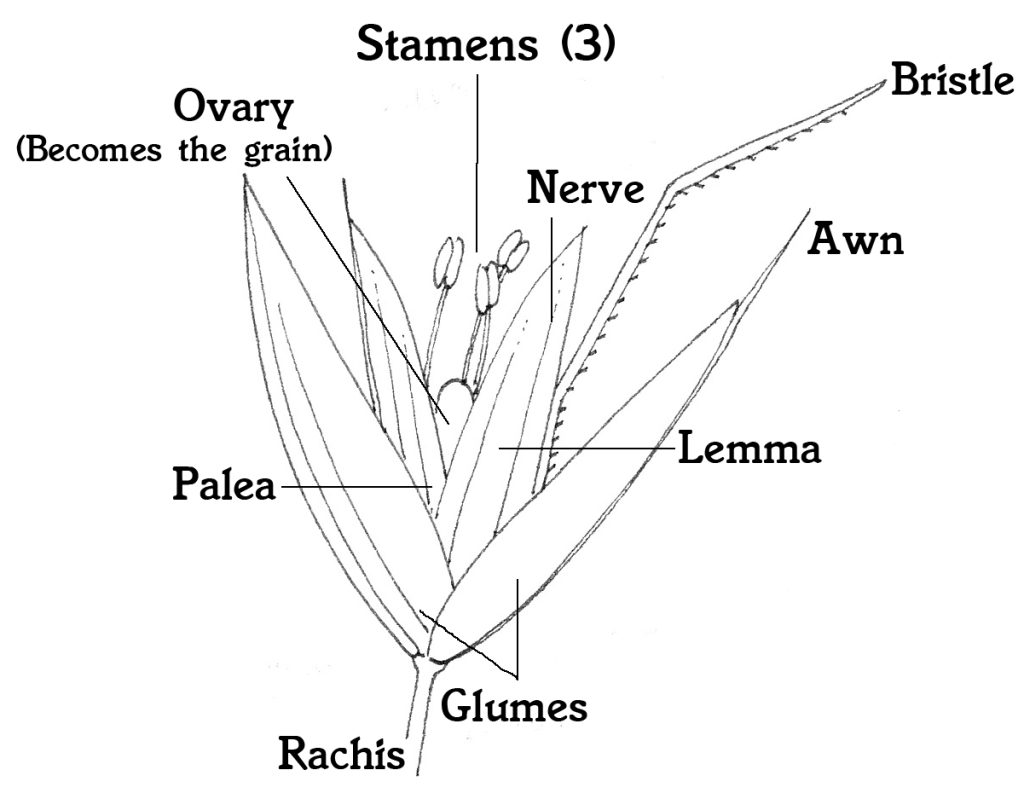

Grass Spikelets

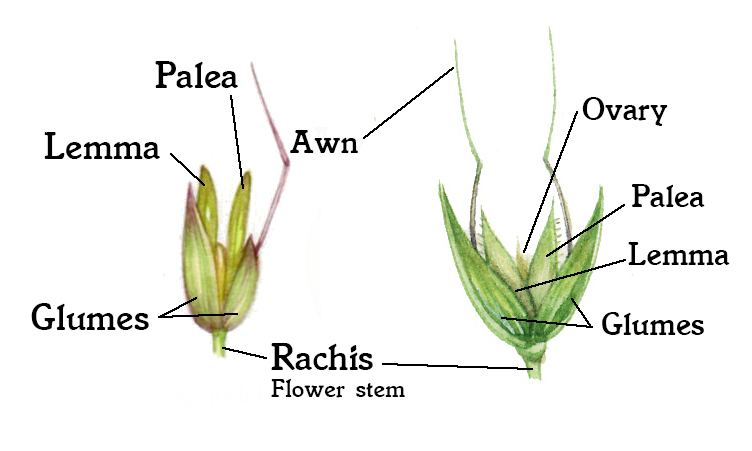

Each individual spikelet, or flower, is made of distinct parts. The stalk of each flower is called the rachis, and flowers are arranged alternately, or in a zig-zag fashion along it.

The base of each spikelet, be it one or several distinct flowers, is held in a pair of glumes. These paired glumes have distinct upper and lower glumes, and these structures are important in determining grass species.

The glumes may have bristles or spikes attached to them. These are called awns, and can be long or short, bent or straight, twisted (as with many Oat Avenaspecies), or absent.

Diagram of an individual grass flower or spikelet

Inside the glumes is the floret, which is the stamens and styles of each flower enclosed by two further scales or bracts, the lemma and the palea. You’re down to hand lens work now, but characteristics to look out for are nerves along the middle (or lack of nerves), awns (or lack of awns), hairiness or not, and colour.

Normally, there are three stamens bearing anthers per spikelet; these often hang out beyond the flower; look closely to find purple ones (Timothy grass and Meadow Foxtail), orange ones (Orange foxtail), white, or cream anthers (many of the Bromes). False oat grass Arrhenatherum elatius has bright yellow stamens.

False oat grass Arrhenatherum elatius with yellow stamens and Meadow Foxtail Alopocerus pratensis with purple ones

Tillers

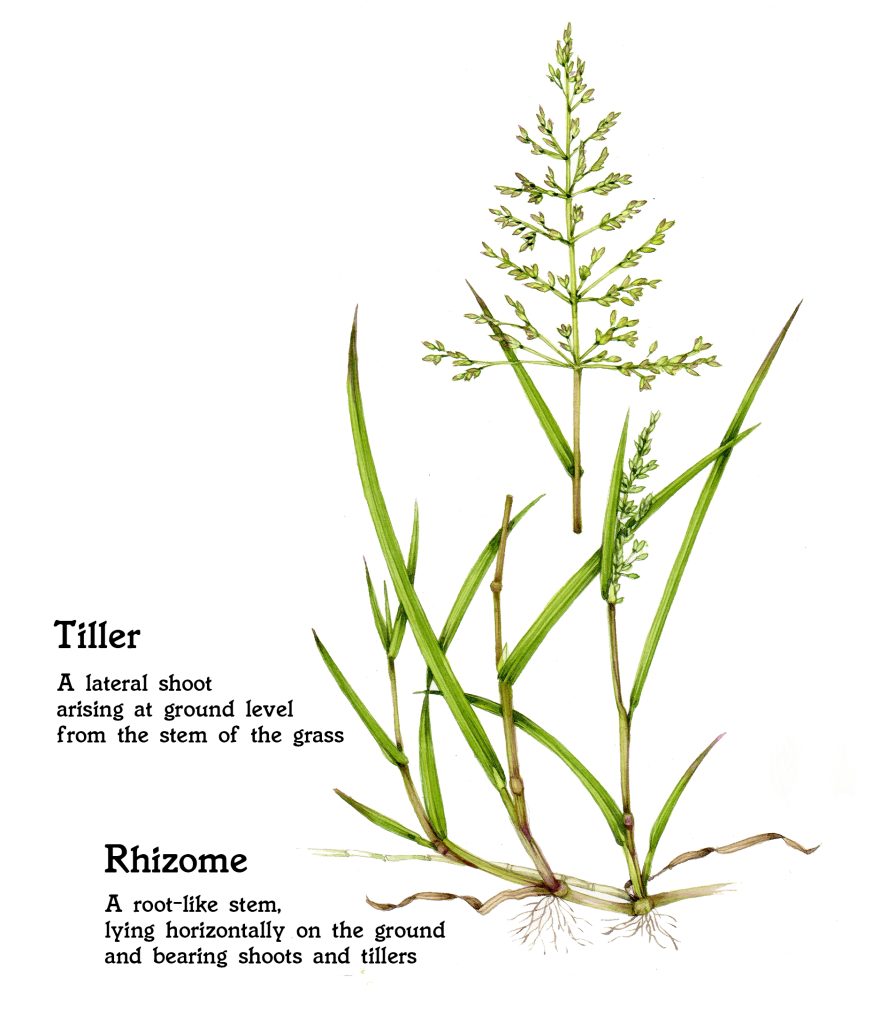

Some grasses put out lateral shoots, sometimes at quite a distance from the main plant. These are known as tillers, and grow from horizontal rhizomes, or root-like stems which grow along the ground. Grasses can rapidly colonise new habitats with this vegetative form of growth.

Tiller and rhizomes, shown on the Rough meadow grass Poa trivialis

Identifying grasses species: Features to look out for

Habit and habitat

What area is the grass growing in? Is the ground wet or dry? Calcareous or acidic? Disturbed? What season is it?

What shape and height is the plant? Is it erect, tufted, or droopy? Likewise, are the panicles tight or drooping, compact or loose, many branched or not?

Does it have rhizomes and tillers?

Leaves

How long and how wide are the leaves? Are they hairy or smooth? Flat or inrolled and bristle-like? What colour are they?

Ligules

Fold the leaf blade back from the stem and find the ligule. Look for its size, shape, edge, presence…

Spikelet

How are these arranged on the stem? How big are they? What colour? What texture?

Spikelet parts

Compare the size of the 2 glume scales, the number of nerves, awns or not, hairy or not. Are the palea and lemma awned or not? How many nerves do they have?

Spikelets of False oat grass Arrhenatherum elatius and Common Oat grass Avena fatua

If you’re interested in learning more about British and European grasses, there are some really good reference books out there. The “bible” of grasses is C.E. Hubbard’s Grasses; Colour Identification to the Grasses, Sedges, Rushes and Ferns of the British Isles by Francis Rose, Collins Guide to the Grasses, Sedges, Rushes and Ferns of Britain and Northern Europe by Fitter, Fitter and Farrer. You could also take a look at Collins Flower Guide by Streeter although it’s rather arrogant of me to suggest this as the grasses plates were all completed by me (with a great deal of help from David Streeter!)

I hope you’ll give the grasses a chance, and end up loving them as much as I do, their beauty and diversity is mind-boggling.

Really beautiful. I love your work

Thank you so much. That’s a really generous comment.

Clear and comprehensive. Thank you

Hello Joan

Thanks for the positive feedback. It’s good to know my explanations are clear, and don;t muddy the water even more! Thanks. Yours, Lizzie

Dear Prof. articulation above/or glumes the glumes.

You’ll have to forgive me I’m 82 years old and trying to key out grasses. Nothing better to do with my time trees in forbs to be much easier. Sometimes ecology helps. I really stuck on articulation. I understand words that the glumes are located so articulation can be rather confusing: grasshoppers we talk about articulation, with clearness of speech we talk about articulation. I’m trying to understand articulation and glasses: i.e. this a joint like a line or is it an action when the seeds fall on the ground would appreciate your response. Gene Clement.

Hello Gene

Thanks for your comment, and for calling me a Prof – I wish! Oh those grasses are a nightmare! I’m not surprised you’re confused! It took me absolutely AGES to figure out my lemmas from my glumes, let alone the joys of articulation! I’m still a little hazy on grass flowers now. The articulation of grasses is like the grasshopper meaning; it’s a joint or line of weakness. One definition is: “articulate meaning jointed; usually fracturing easily at the nodes or point of articulation into segments”. SO it applies to the structure rather than to a process. You’re also right that the trees and herbs are less painful, although I properly love the grasses. I found the best way to learn species was to spend a day in a field with a botatnist who knew their species, although in these merry days of Covid19 such a thing seems little more than a pipe dream…

Another resource you could use, if it appeals, is twitter. There are very friendly nests of botanists there who would readily help you i.d. a grass specimen. Then, once you know for sure what you’ve got, you can work backwards with the keys. I always start out with keys by going from definite knowledge backwards. Eventually the terms make enough sense for you to use keys in the way they’re intended!

Good luck, and I love that you’ve discovered a passion for grasses, we’re never too old to learn new stuff.

All the best, stay well, and good luck with those articulated glumes!

X Lizzie

Lizzie, your work is impeccable. I absolutely love botanical illustration, and yours are some of the finest I have had the pleasure to look at. This entry is extremely well thought out, explained, and illustrated. Thank you for gracing us with your work!

Hi Cameron

Thank you so much! What a generous and flattering comment, its lovely. Its so good to get positive feedback on work, so thank you!

Great resource, been taking some time to better understand, grasses, sedges and rushes while on lockdown. I have also shared your blog with my Forest School learners as a useful resource. Do you have a similar write up on umbellifers? Thank you.

Hi Duncan

So glad they were useful! I love your query re umbellifers. In fact, I’m so wobbly about my umbellifers that I’d booked myself on a one-day course with the Field Studies Council to sort them out, and would inevitably have done a blog. The course will probably happen in 2021, so once I’ve learned a bit I will definitely be here spouting and sharing what I’ve been told! Thanks for the comment and the suggestion, you’re clearly on the same wave length as me! Yours, lizzie

Lovely site, and a wealth of knowledge here. I am trying to get a quick primer in grasses, as I posted a photo on iSpot this week and the general consensus is a bit split. It is likely to be Hungarian Brome – but I promised to go back and take some more shots now I know just what to concentrate on. Also I spent most of my life in graphic design and I admire your beautiful watercolour drawings – my battered and dog-eared Marjorie Blamey handbook was my introduction to British wildflowers!

Hi Anthony

Lovely to hear from you! Ah yes, the joys of Bromes. Yeah, if you take a close look at those spikelets and ligules, and where hair does or does not grow… It’s funny, I’m obsessed by grasses but am still really poor at identifying them in the field. I was due to take yet another grasses i.d. course with the Field Studies Council before lockdown. Next year, maybe. Thanks for being nice about my work, much appreciated. Ah yes, Marjorie Blamey. My bible is the pen and ink line drawings of Stella Ross Craig, look them up if you want to see how atonal black and white images can totally capture the nature of a plant. Such a clever woman.

Enjoy your grasses and your Hungarian Brome, and good luck with a definitive id. The goodly folks on twitter are SOOO helpful with identifications; you might check in with @BSBIbotany @botanicalmartin and @drmgoeswild who has a particular soft spot for grasses…

Enjoy!

Hi Lizzie,

A book I would highly recommend for studying the grasses is “Agnes Chase’s First Book of Grasses.” This is a must have for understanding grasses and the somwhat complex terminology describing their anatomy. I have both a first edition and the more easily acquired 4th edition.

Thanks for your fine work/color drawings (watercolors?).

Brad Reiser

Hi Brad

That’s a great tip, I shall go and invest in one immediately. Good books on grasses are hard to come by, thanks for the recommendation, and for your generous comments. X lizzie

Thank you for sharing this article. I have struggled for years with the terminology. My husband, a range management specialist, will state “look at this raceme” and I would just smile and say “yes honey” not having a clue what he is really talking about.

This is so very helpful! Thank you for putting in short simple narrative that is understandable.

Hi Catherine

That warms the cockles, I do try to untangle all the terminology as much for myself as for others. So Im relieved it makes sense. How funny, I can just picture the patient smile as you wait for him to stop going on about glumes and ligules. Hopefully now you can come right back at him, “yes, but honey why hasn’t it got angled awns?” or “I just love the way this species has an inflated sheath, don’t you?” Just be sure you dont use the grasses terminology on sedges or rushes (my head starts spinning…) or he’ll smell a rat! It does seem like a whole lot of learning to be able to talk about these plants. I still havent sorted out the mosses, oh gosh, no.

Thanks for your message!

Yours, Lizzie

Hi Lizzie,

I’m a student studying agriculture and this has really helped to explain everything and simplify it. I am trying to do assignments and I have an exam coming up so this will really come in very handy. Thanks so much for posting this.

Regards,

Caoimhe

Hi Caoimhe, what a lovely comment. SO glad it’s useful, and good luck with your exams!

Hi Lizzie,

Thanks for sharing this beautiful guide, as horticulture student I have found it really practical. Thanks for sharing your knowledge!! 🙂

The illustrations are astonishing

My absolute pleasure, and thank you so much for your kind comments. When I first had to illustrate grasses, I was totally confused, so that’s lovely to know that this helps others who’ve had that same moment of doubt!

Dear Lizzie your work on grasses is beautiful! I’ve been working with a poet pal Valerie Gillies on a poetry and photography project called ‘When the grass dances’. The grasses carried us through the last years! Offering their story of resilience and renewal. Your work on their structure is so well laid out. Thank you!

Hi Rebecca

What a fascinating project! And they ARE extraordinary plants, I entirely agree. I just went on yet another course on grasses at the weekend (I cant get enough of them) so expect more blogs on them in the next few months! SO glad you share my passion, and thanks for the kind words about my work.

Thank you very much for this clear explanation of grasses. I am trying to identify

native grasses on our bush property in Australia & have been struggling to understand the

botanical terms used in references. Your guide is very helpful. Thank you.

Hi Kathy

Delighted to hear my blog is useful. Thankyou!

Lizzie

Hi Lizzie. Have you any tips on the technique of dissecting grass flowers. It’s just the start of the grass season in the UK and I am looking at Sweet Vernal Grass. Apparently it has two infertile florets and one fertile in each spike but I am finding it really difficult to separate the spike to see these details. Thanks. Paul

Hi Paul

Not easy, is it? Especially when some books and sources say one thing, and others may not agree. For dissecting grass florets, a dissecting microscope is a big help. I also use tiny tailor’s scissors, a needle to separate the florets from one another, and a razor blade or scalpel to cut individual florets off the main inflorescence. A trick I use sometimes that might be of use is to do your dissecting on a bit of masking tape. You can mostly still move the individual florets around (if you don’t push down too hard) and they don’t flip about or disappear when you go in to see the detail. Sweet vernal grass is so lovely, the way is smells so strongly of hay. But in truth I’ve not seen the fertile vs unfertile flowers myself. They are probably there, but sometimes I wonder if these species diagnostics are invariably present? Or maybe wait til a touch later in the season when the individual flowers are more mature and possibly less scrunched up together? Not much help, Im sorry. Good luck with it, hope you find the infertile vs fertile ones.

Thank you for your gorgeous and informative work!

I found you whilst trying identify a grass. Do to you and the links, I learned it is a glaucous sedge.

Hooray for you, Julie! Sedges are even trickier than grasses, I think, so that’s wonderful to hear.

Stunning drawings! I’m a rancher and very interested in grass. I am so envious of your skills as an artist!

Ah, I may be able to draw grasses, but Im sure you know an enormous amo0unt more about them than I do! So I am jealous of your knowledge. Yours Lizzie

Good day Ms. Harper,

I am an ecological consultant trying to help rural African people to manage their grasslands better. We have produced a series of very basic booklets which we explain by means of power point presentations. I came across your work and it is the best that I have seen. Would you consider letting us use two of your grass plant illustrations for our booklet on grass management and our power point on the subject. We hope to present in Rwanda and Ghana to groups of leaders in the conservation/agricultural field. I will of course acknowledge you as artist and author on each illustration.

Yours sincerely, Ken Coetzee.

Hi Ken

What an interesting project, and yes, this is certainly something I’d be able to help with. Please email me on info@lizzieharper.co.uk and let me know which grass species you are interested in using. Thank you for your lovely comments about my work, too.