Botanical Illustration – Tips on painting Composite flowers

When doing a botanical illustration of a flower, a bit of basic botany helps enormously. This week, I’m going to discuss a really abundant plant type; the members of the daisy family (the latin term for these plants is Asteraceae, formerly known as the Compositae).

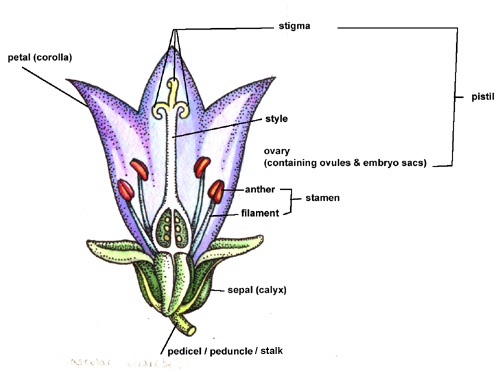

The terminology of flower parts can be complex, so below is a labelled diagram, adapted from an illustration I did for The New Amateur Naturalist by Nick Baker.

(For a clear and more detailed overview of general flower anatomy and funtion, have a look at the RHS slideshow.)

Asteraceae or Daisy family overview

The daisy family has the most species within it, after the grasses. Lots of familiar flowers like thistles, daisies, ragwort, and dandelions fall into this group. The amazing thing about these flowers is that each individual flower head, each daisy or dandelion, is in fact, a cluster of many tiny flowers (known as florets). These florets come in two forms; ray florets and disc florets. Both floret types are formed of five joined petals which either form a tube (disc floret), or a short tube with one lengthened lobe or strap which extends outwards (ray florets). The assemblage of florets are called a flower head, or capitula.

Ray florets

Ray florets tend to be larger than disc florets and often form an outer “ring” of a composite flower (think of the white “petals” of a daisy). The disc florets can be tiny, and form what we often think of as the centre of a composite flower (the brown area of a sunflower, the yellow centre of a daisy). If you have a dissecting microscope, or even a 10x hand lens you can see these two types clearly; just tease a daisy apart, preferably over a black background.

Generally, surrounding the florets is a ring of small leaf-like bracts which vary in size and shape according to species.

Now, not all members of the daisy family have both types of floret. Some only have disc florets. Some only have ray florets. Some do, indeed, carry both types. Below are some examples of all three types.

Composite flowers bearing only disc florets

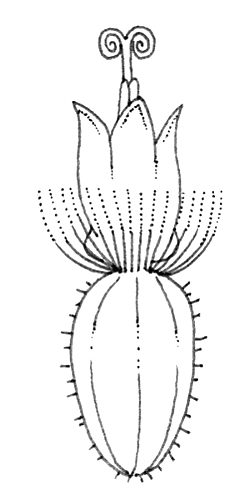

Thistles and similar flowers are Asteraceae representatives which only bear disc florets, as is tansy and cornflower. First, let’s look at a common knapweed.

This flower head is borne at the tip of a stem, and made of identical purplish disc florets. The base of the flower head is overlapping bracts; and the brownish hairy appearance is due to the edges of these bracts looking feathery or fringed.

Don’t be fooled by the larger, star-like florets you may see at the outer edge of some knapweed flower heads. these are also disc florets, but are sterile and enlarged; their star-shape is due to deep lobing.

Knapweed flowers progress form male to female with time, so younger (male) flowers cross pollinate older (female) ones (thanks to insects).

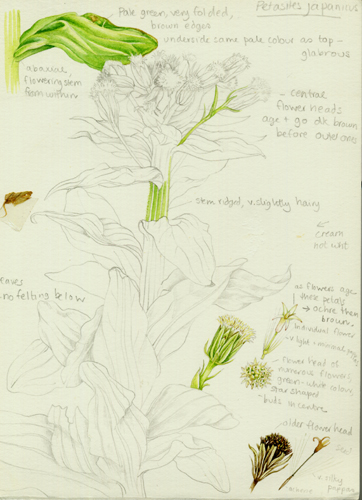

Butterbur is a wonderful plant; it’s leaves only appear once the flowers have died. Female and male flowers (all are disc florets) appear together with the females on longer stalks and developing into plumed seeds.

This butterbur illustration I did is from Collins’ Flower Guide (butterbur species at bottom and top left); below is a sketchbook study.

Composite flowers bearing only ray florets

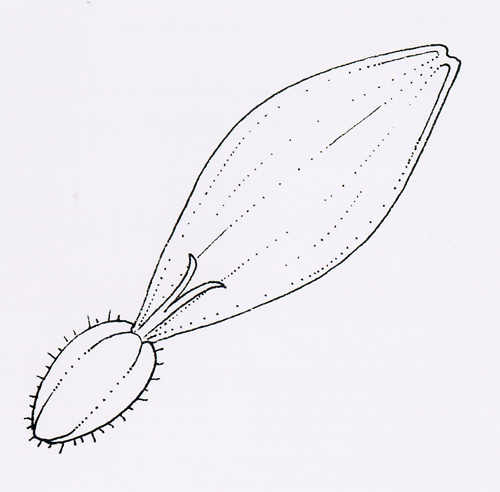

Species carrying only ray florets include the dandelion and its allies, chicory, salsify, and lettuces. Let’s look at the dandelion.

The 200 or so ray florets making up the head of a dandelion are hermaphrodite; and close when it’s dark, dull weather, or (devastatingly for the illustrator) soon after being picked. The bracts help distinguish dandelion from similar species; there’s an outer ring which spread and an inner set which remain erect. Dandelions carry each seed at the base of a parachute of hairs on a long stem; before the wind disperses them these form the distinctive dandelion globe-like “clock”.

Another species bearing only ray florets is chicory, which is a joy to paint as it’s such a glorious blue.

Composite flowers bearing disc and ray florets

These plants carry both floret types, with rays round the edge of a group of disc florets. Lots of the Asteraceae fall into this group; along with asters and sunflower, there’s also yarrow, rudbeckia, fleabane, ragwort, burdock, arnica, marigolds…

The Ox-eye daisy is made of white female ray florets surrounding yellow hermaphrodite disc florets.

The sketchbook study shows the arrangement of the disc florets; it’s worth remembering that they are formed by two spirals winding in opposite directions. This helps plot the position of each disc floret.

Also remember that the disc florets in the very centre of a flower head will be the last to mature, flower, and subsequently form seeds. This is particularly helpful with the sunflower.

The sunflower is a lovely specimen as everything about it can be so large, and so easy to dissect out and examine. The colours of the disc florets are particularly interesting, with age they can become dark brown or even a deep purple.

I hope this rather botany-heavy blog has helped show the amazing variety, and wonder of the Asteraceae or daisy family. The more you think about the scale of these tiny florets all forming one flowering head, or examine the details of each ray floret, or the pattern formed by hundreds of tiny disc florets; the more wonderful they seem, and the more I want to investigate and draw them. Many thanks to members of the Botanical Art for Beginners group for suggesting this as a blog topic; click on the link for more information on the Asteraceae family.

Thank you for this! I too am a scientific illustrator but have specialized on insects and the occasional fish. For several years I have been photographing goldenrod to capture the amazing number of species of insects that depend on it; we live in the US in western New York State where goldenrod is practically the climax plant for the fall. Recently I have been trying to draw some goldenrod flowers, but have had difficulty puzzling out its structure. Now I understand the structure at a different level and understand more of why I was stumped!

Best,

Margaret Nelson http//www.margynelson.com

Hi Margaret

Goldenrod is spectacular, and amazing for insects. You’ve reminded me of the work of Emily Damstra, who wrote an amazing article on the insect-plant interactions on Goldenrod in the GNSI journal. Here’s a link to her portfolio where you can see some of her goldenrod work: https://www.emilydamstra.com/my-portfolio/plants-lichens-fungi/ You two share a passion!

Yes, I understood asteraceae/ composite flowers very late on and still marvel that each little yellow dot is indeed a disc floret, an individual flower. Im so glad that sharing some of this info has been helpful for you.

Enjoy the project, it sounds like a wonderful one!

Yours

Lizzie