The Hidden Universe: Pen and Ink Illustrations

The Hidden Universe by Alexandre Antonelli is a short and powerful book. I was asked to provide pen and ink illustrations, and had the absolute luxury of reading the whole book before lifting a pencil. This may not sound unusual to you, but in all the years I’ve been illustrating books, it’s only the fourth time I’ve read the manuscript ahead of publication (in the summer, but feel free to pre-order the book).

Cover of The Hidden Universe (not my artwork)

Alex discusses the importance of biodiversity from a genetic to an ecosystem level. He talks about the impact and importance of the climate emergency, and presents the reader with lots of entirely new examples to ponder. The book is full of optimism too, detailing what we can all do, and what is already being done to wrestle back our planet into a salvageable home for all of life.

He’ll be appearing at Hay festival on May 29th (11.30 – 12.30), talking about the book.

The Hidden Universe: Pencil roughs

I got a detailed list of illustrations. There were about 20 on the list, and between me, Alex, and the art director; we whittled it down to around 14. This was surprisingly easy, and all my favourites are included.

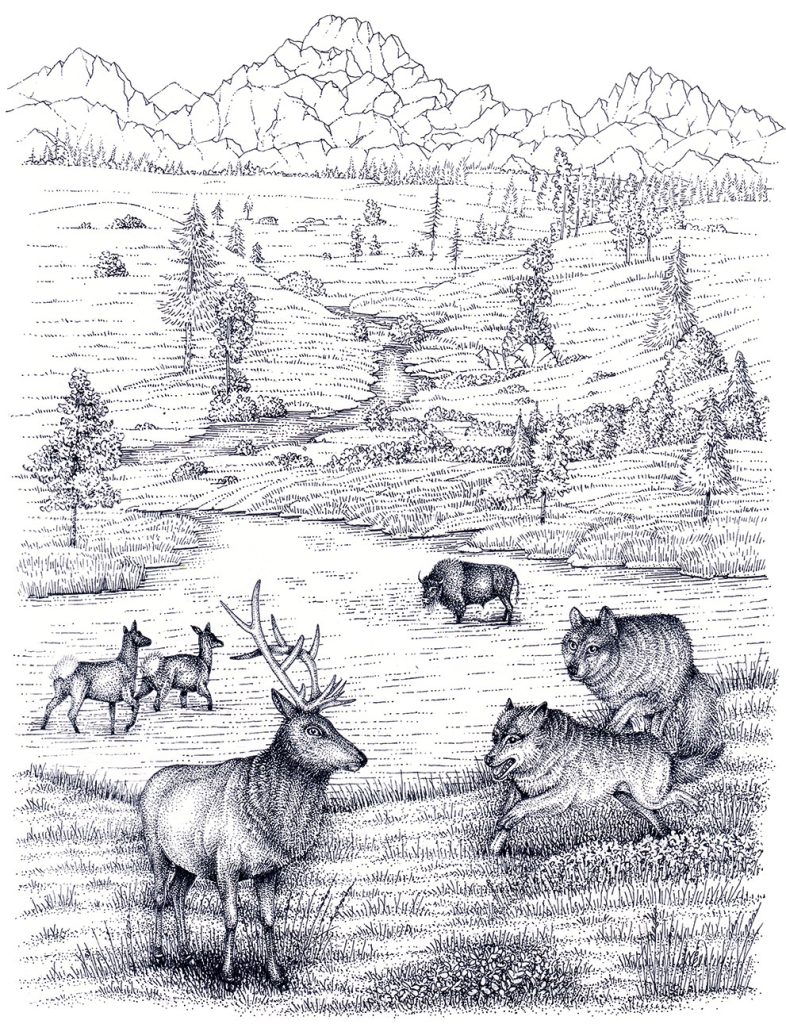

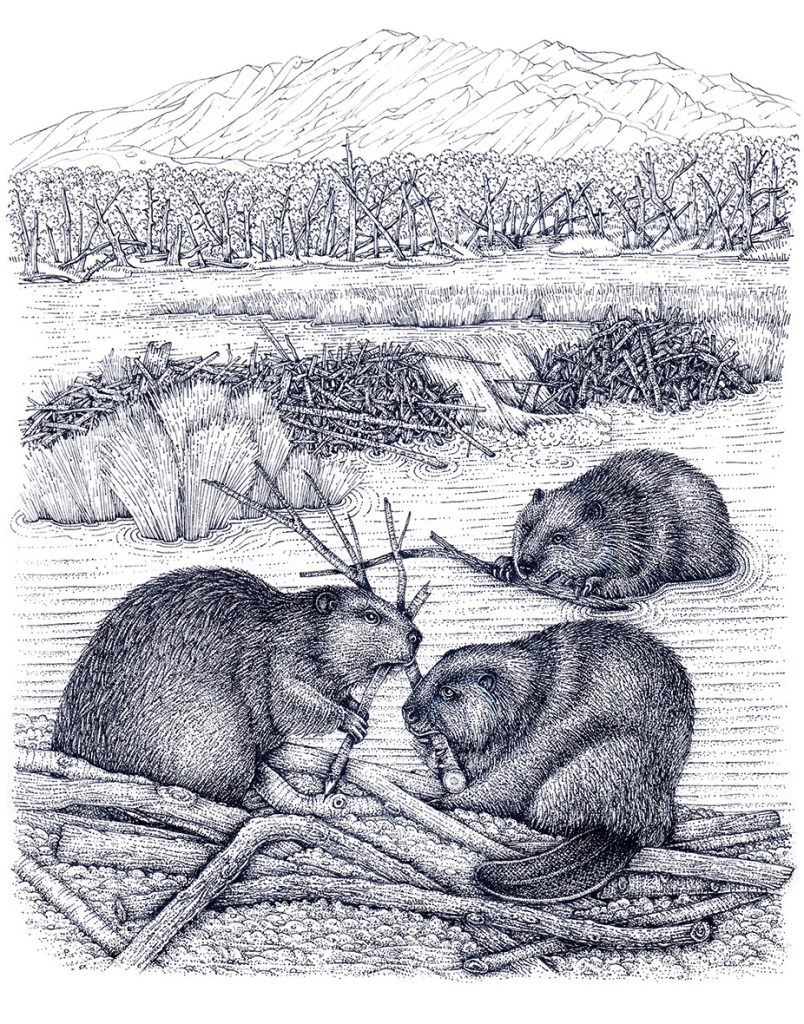

The subject matter for the illustrations is extremely diverse, and often challenging. Some are simple, such as the extremely rare Cretan orchid Cephalanthera cucullata. Others have multiple elements. like the hedgehog in a log-pile. Three are extremely complex (Wolves back in Yellowstone park, Beaver in Tierra del Fuego, and Rocky shore zonation.

Cretan orchid Cephalanthera cucullata

I drew up all of the illustrations in pencil, and was delighted when the returned feedback was overwhelmingly positive. I was especially relieved about the three toughest ones. The background skyline of one needing altering, but none of the animals did.

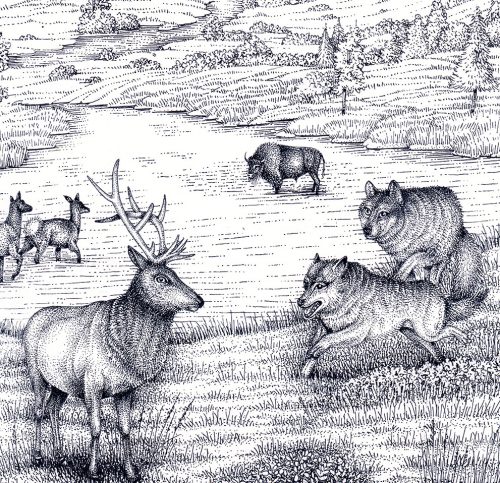

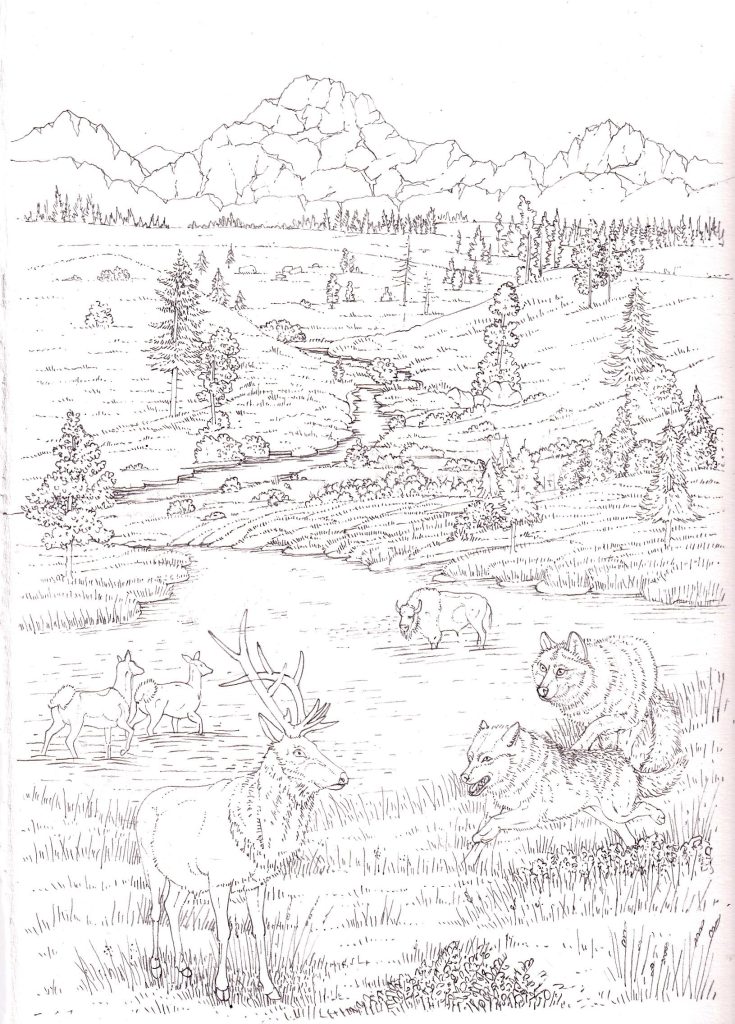

Yellowstone national park showing re-wilding

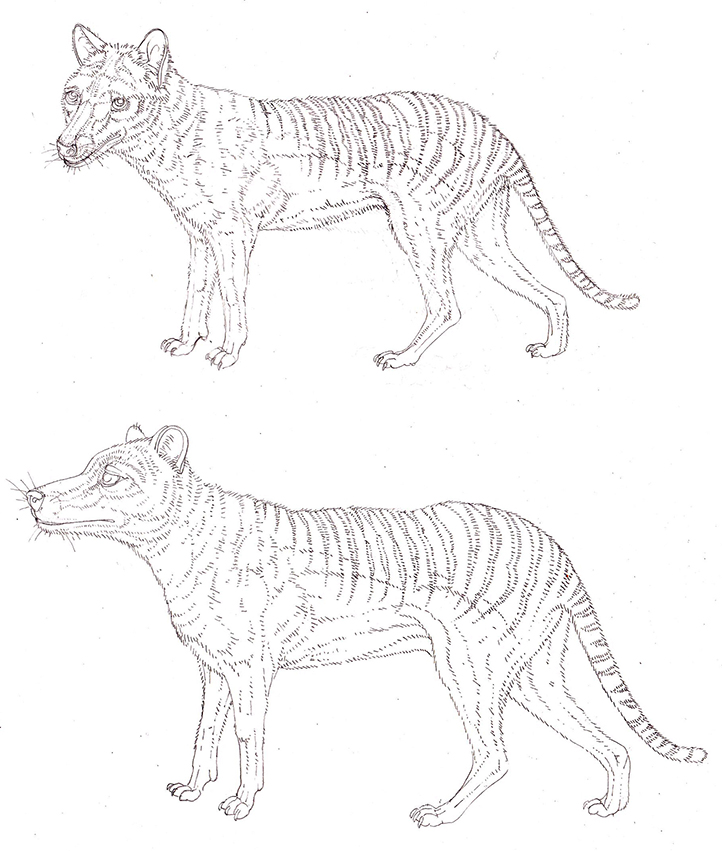

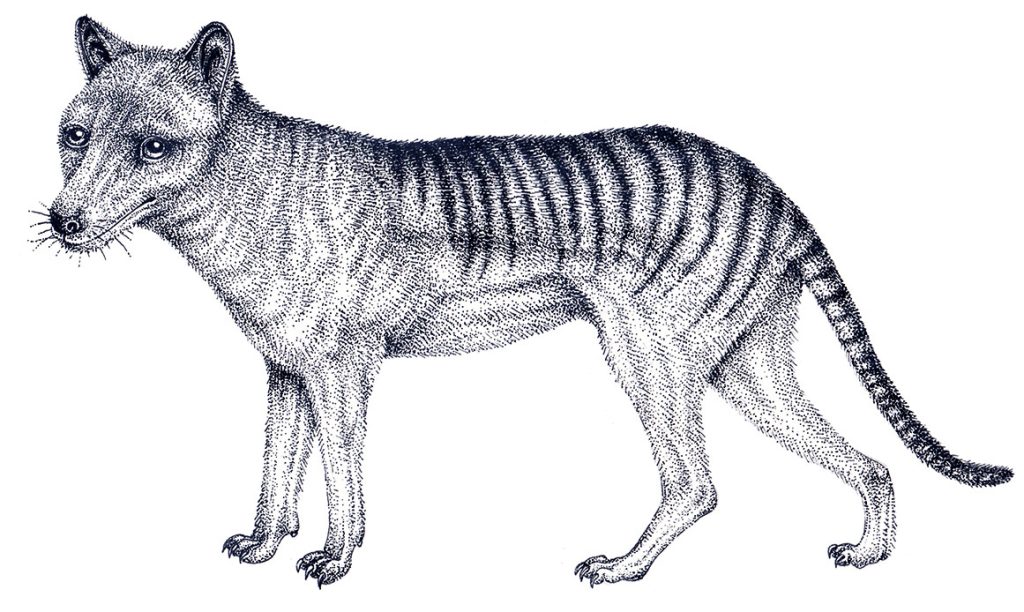

One illustration, the extinct Thylacine or Tasmanian wolf was a matter of choice. I provided two pencil roughs for Alex to contemplate. He chose the one he feels is more engaging, the top one.

Thylacine rough x 2 Thylacinus cynocephalus

Below is the final inked up version.

Thylacine Thylacinus cynocephalus

The Hidden Universe: Yellowstone and Re-wilding

Instead of listing the illustrations I did for this project, or discussing the drawing process; I’m going to talk about a couple of them in detail.

First up is the rough I’ve posted above, Yellowstone national park, and re-introducing the wolf.

In the illustration below, a wolf pack hunt an elk. Behind is the craggy landscape of Yellowstone national park, and (importantly) lots of trees. There are more deer in the background, and a bison. This illustration illustrates two ecological concepts. The first is re-wilding.

Wolves hunting deer in Yellowstone National park

By re-introducing wolves to the park, you balance the deer population. Less deer means less grazing on young trees. More trees means more birds and other associated wildlife. More wildlife means more recycling of nutrients in the ecosystem. It’s a healthier place to be. I first read about this example years ago in George Monbiot’s Feral. I never thought I’d have to try to explain the story in an illustration!

The second concept is linked. It relates to the idea of keystone species and a biological or ecological cascade. Some species are vital and make the whole web of life in a habitat work well. Take one species out, the keystone species, and the whole natural system collapses. This happened in Yellowstone. All the wolves were hunted or removed by man. Remove a top predator like the wolf from a system, and it can trigger what’s known as a trophic cascade. Too many deer, not enough trees, no associated wildlife…the system collapses. It’s why the re-introduction of wolves to Yellowstone is so exciting (and so very successful).

The Hidden Universe: Beavers and Tierra del Fuego

Another of the illustrations involving a lot of work was the beaver dams in Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago off the coast of Chile and Argentina.

This seemingly charming image tells a darker tale.

Fifty Beaver Castor canadensis were introduced here by man in the 1940s. (Introduced species are almost inevitably introduced to very new and far-flung location by man). The theory was that they would breed, and a fur industry could be established. They began to do what beavers do. Breed. Fell trees, and build dams. The dams create large pool and alter the water courses.

Close up of a Beaver

In many places, this is totally beneficial. Beavers have recently been re-introduced to Devon, in the UK. Their landscaping has had massive and many unexpected benefits to the local area. Flooding is less. The slower flowing water creates new habitats and havens for wildlife. Even the water quality is improved as the dams act as filters. For more, read about the Devon beaver re-introduction here.

Beavers and dams in Tierra del Fuego

Why Beavers in Tierra del Fuego did not work out

However, Tierra del Fuego is a closed system. This means there are only a limited number of trees, and as it’s an archipelego of islands, new colonising species are infrequent.

The beavers have no natural predators here, so have bred very successfully. In Canada, where they were imported from, wolves and bears prey on them. By 2011, there were estimated to be 200,000 beavers in the area. (NPR 2011)

Problems include flooding, which damages other vegetation. Trees in South America did not evolve alongside beaver (in the UK, beavers were present until only a few hundred years so, so there was co-evolution). These trees die rather than regenerate when coppiced by beaver.

Many of these trees are protected species. Many are already dead or dying.

The resulting chaos and scenes of devastation mean that a cull is almost inevitable. As Professor Anderson, from the Universidad de Magallanes, says, “The change in the forested portion of this biome is the largest landscape-level alteration in the Holocene — that is, approximately 10,000 years” (Nature 2008)

It is not an edifying example of man interfering in nature.

Hidden Universe: Hope and A Hedgehog in a log-pile

The last illustration I want to talk about is the hedgehog in the log-pile.

This image comes from a lovely section of the book. Alex fills the pages with suggestions of what we can do to save what we have. Examples of things that are already being done.

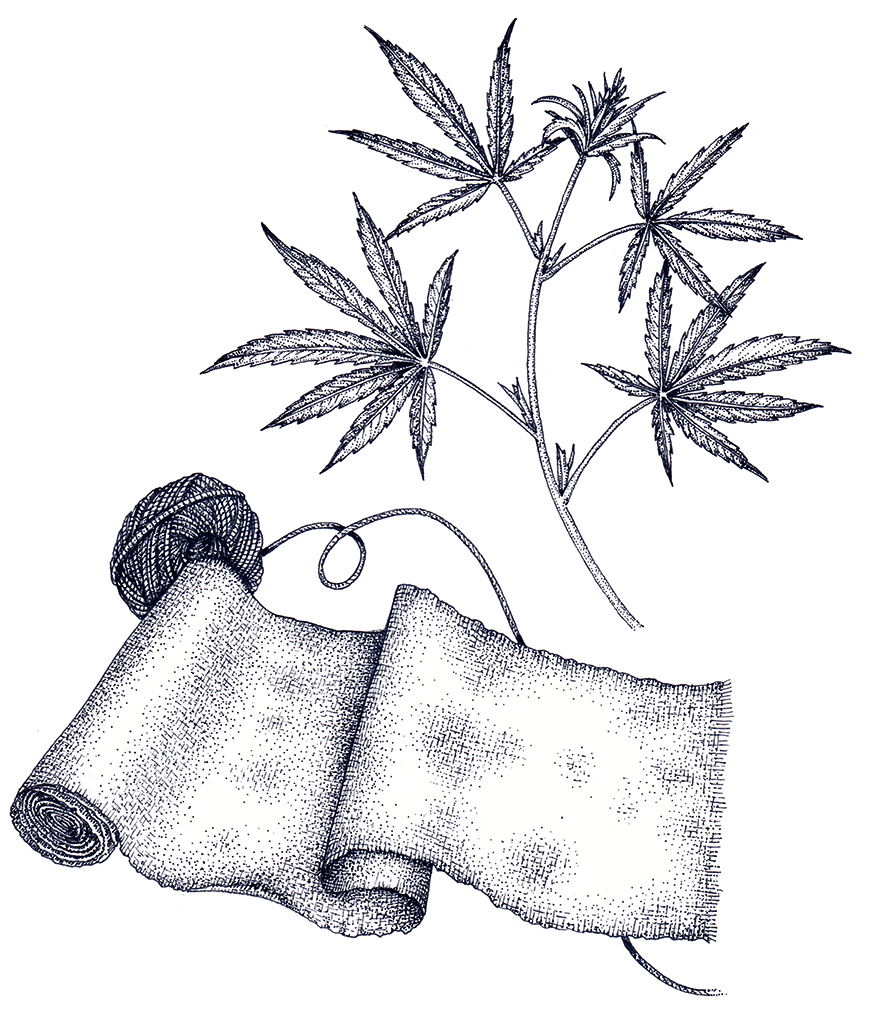

Hemp from Cannabis sativa

How making cloth and ropes and twine from hemp is a really good alternative to cotton. The plant is far less water-hungry, and farming it can be much more ethical and ecologically sound.

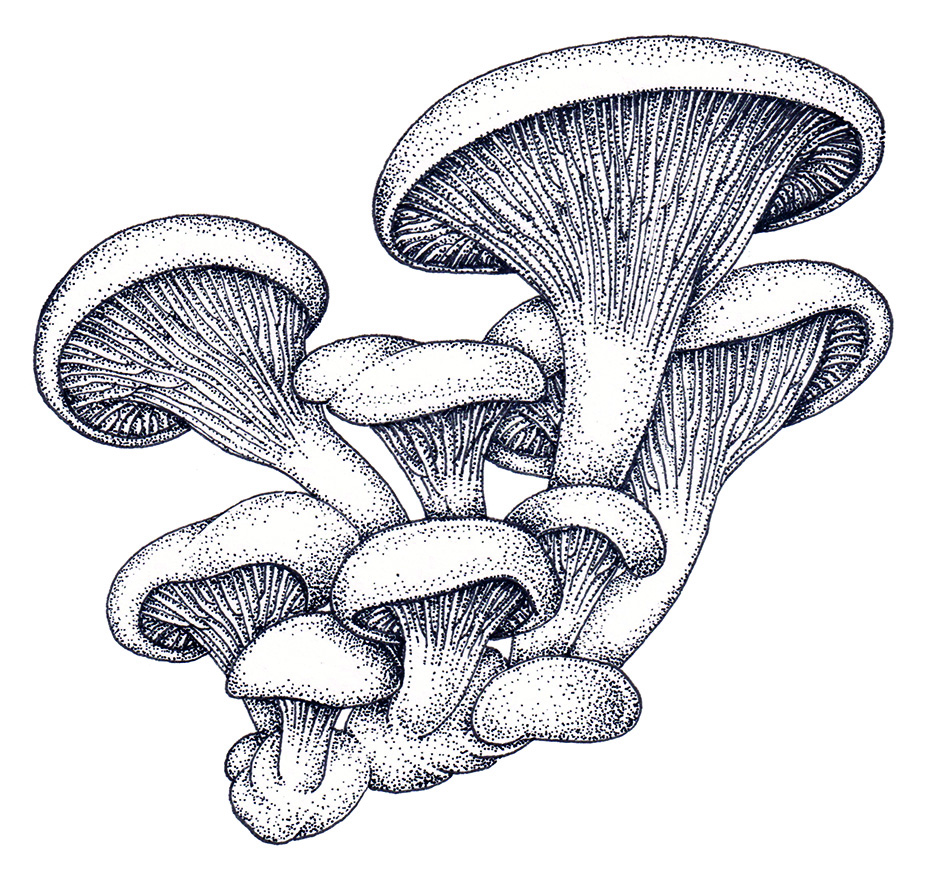

Fungus, the solution to a whole lot of problems. It can (and should) be further exploited for food resources, but has other applications such as the building trade (see my guest blog on this from years ago for more).

Oyster mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus

There are lots of other examples. Some I illustrated, some I didn’t. All gave pause for thought, and many gave hope.

Hidden Universe: A Hedgehog in a log-pile

Which brings us onto the hedgehog. It’s drawn by a mouldy log pile in amongst long grass. Nettles and ivy are established. To a traditional gardener, it’s a messy scene.

Hedgehog

This illustration shows how easy it can be for a lone individual to do something small, but which makes a tangible difference. Allow a corner of your garden to get overgrown. Don’t pull up nettles. Leave a few logs and sticks in a corner. Let the grass grow long. leave the area undisturbed.

You may find you’ve made the perfect home for a hedgehog.

hedgehog

Even if not, the longer grass is wonderful for insects, spiders, harvestmen. In turn, this is beneficial for the small mammals that feed on them.

Allowing nettles to grow provides food for caterpillars of both the Small Tortoisheshell and the Peacock butterfly.

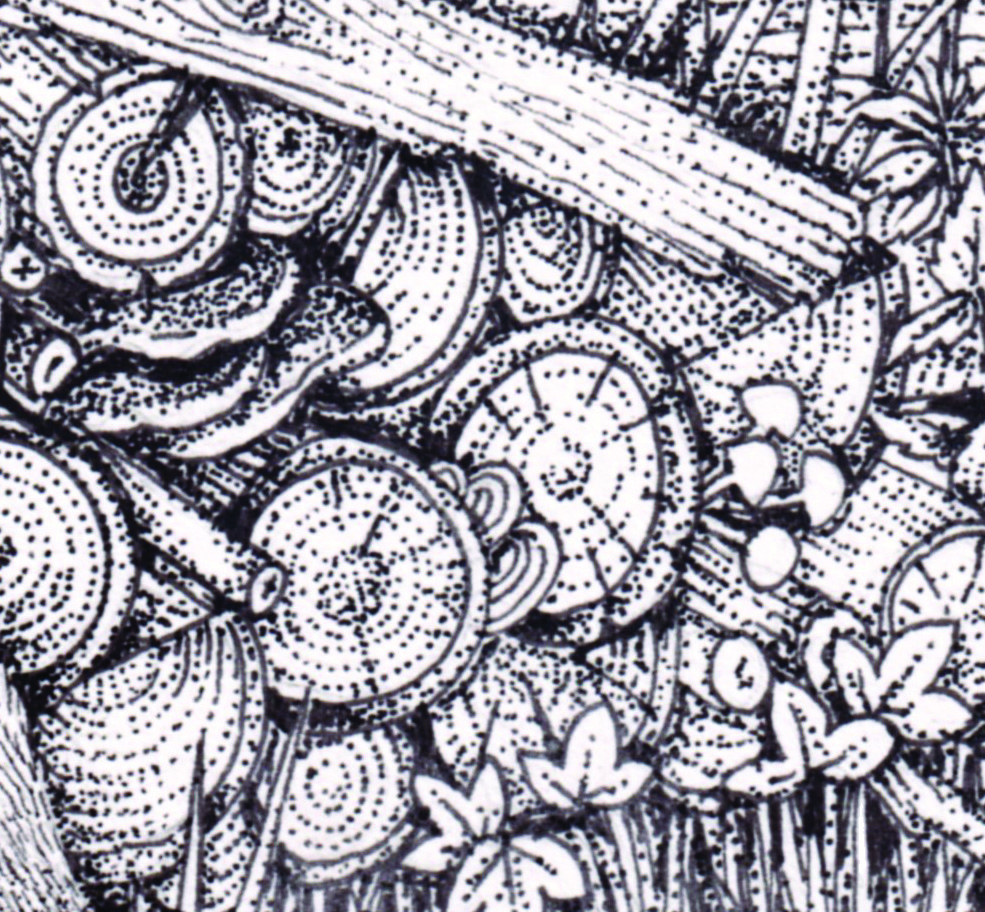

The logs themselves allow all sorts of fungus and bracket fungi to thrive, which in turn breaks down the wood and helps return the nutrients to the soil.

Detail of log pile with fungus

It’s all so good. And all so easy to do. Wildlife gardening (for this is what we’re talking about here) doesn’t have to be difficult. It can be as easy as letting a corner get overgrown. And the benefits to the entire ecosystem are enormous.

Conclusion

So there you have it. The tale of three illustrations from The Hidden Universe. It’s a book that’s well worth reading, not least because it doesn’t end up filling one with a sense of apocalyptic dread. There are things to do, and things being done.

Cycnoches guttulatum orchid with Euglossa cybelia orchid bee

It also shows how enormously fortunate I am to have the job I have. Every illustration I do entails some learning. Sometimes it’s botanical details. Occasionally it’s how to reconstruct an extinct animal. This time, it was both of these; and how to illustrate entire ecological systems and concepts. Does it make my brain ache? Yes. Do I love the learning? Yes, indeed. Am I the luckiest illustrator on the planet? Well I might be biased. But I reckon I could easily be.

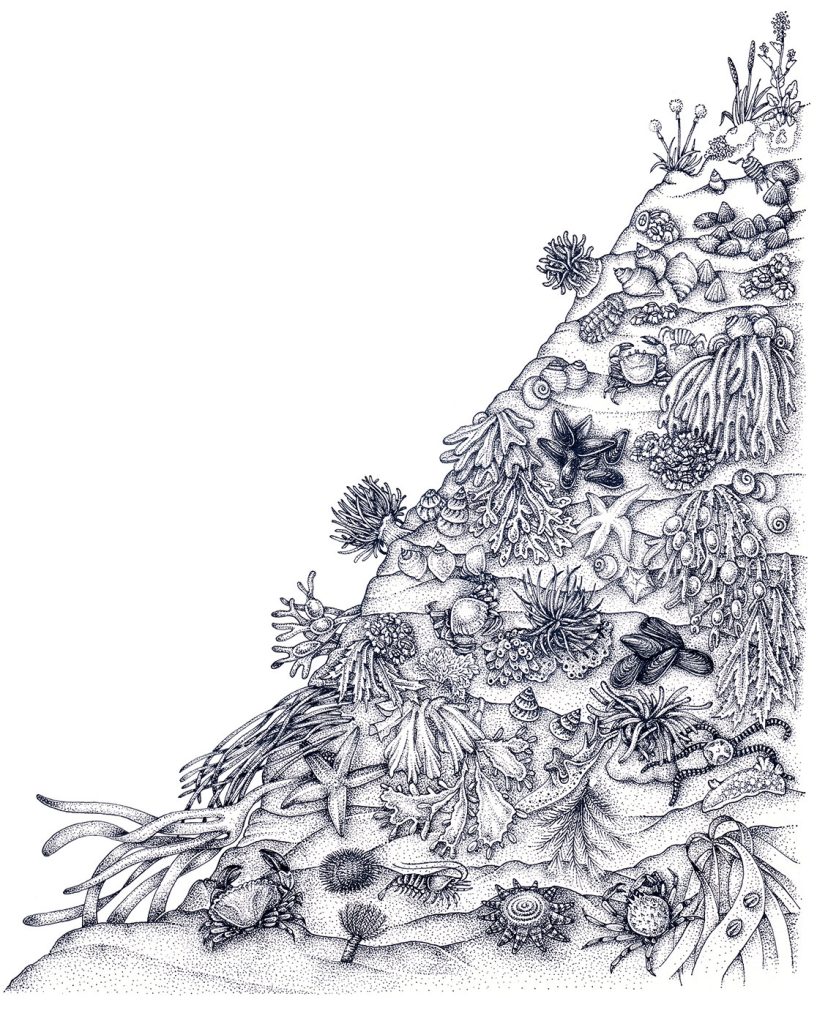

For an extended look at another of the Hidden Universe illustrations, the zonation of a rocky shoreline, I plan to produce a detailed explanation in a future blog.

Rocky shore ecosystem

Very nice and well informed post Lizzie.

Regards Peter.

Thank you Peter.

You are not only the luckiest illustrator out there but also a very good writer. I’ve told you the other day. You have to write a book.

Aww Marialena, you’re always so kind. Writing a book is somewhat terrifying, I do think about it from time to time…and then the next job comes in! But its somewhere in the caverns of my mind, as a neglected idea. And thanks for thinking it might read ok if I ever did write one! Much love XLizzie

I’ve spent an entire morning reading your posts and watching your videos. Many thanks for all the education, especially regarding reintroduction of former native species. As you know, introduction of northern hemisphere species (rabbits, cats, etc.) have done damage to many smaller animals in Australia. Anyway, again, thank you very much.

Hi Constance

My absolutely pleasure. The whole issue of invasive species seems to be really important (and entirely down to humanity’s insatiable need to travel and explore!), whether it’s lupins in Iceland, rabbits in Australia, blackberries in the USA, or Himalayan balsam in the UK. I do always have a sneaking admiration for these creatures and plants that proverbially roll up their sleeves and crack on with colonising these new areas of paradise, unfettered by predators or disease. But yes, the damage they do is profound, and it doesn’t seem that any of the examples Ive come across have found easy solutions.

Thanks so much for your support and kind words

Yours

Lizzie

I love your tassie tiger (Thylacine) picture. This creature adorns the labels of Tasmania’s own beer brand, Cascade. I lived on the island for 18months during my 30’s. It’s rugged, wild and very punishing environment. Not weather-wise, there is an energy there that has a habit of unravelling people’s lives if they need to grow. Many people move there only to need to leave again because their lives fall apart shortly after arriving. It probably has a lot to do with the islands extremely dark history.

Honestly it broke my heart to live there. For while it’s often touted as a pure wilderness, a car drive only a few hours into the interior reveals completely denuded hills from clear felling as the islands main economy is logging old growth forests for wood pulp. I could not bear to witness that, and the strangeness of the place so I left.

Oh, And I forgot to mention that the island was once called the Apple Isle because of the very old orchards there with varieties not grown anywhere else in Australia. But the apple isle is also a name for Avalon, and indeed Tasmania has the energy of that too. Deep, ancient magic.

Hi Clara

What interesting comments. You’ve really piqued my interest about Tasmania. So sad to hear about the deforestation, no wonder if makes the whole island feel odd. I know very little about it, so your comments are interesting.

I also know what you mean about being put off by the complexity of the elder. But its not too bad, actually. Plot out a very pale shape for the flowering head then decide where to start plotting in your flowers. Ever so mindfull… Your champagne sounds delicious!

x

Have you ever thought about creating an ebook or guest authoring on other sites? I have a blog centered on the same information you discuss and would love to have you share some stories/information. I know my viewers would value your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an e mail.

I’d love to do a guest post, but would need guidance on what topic to cover. I’d also need a pretty long lead time as things are busy…but yes, in theory that sounds lovely. Could you pass on a link to your blog so I can take a look and see what might be relevant? And thanks.