Variegation: Patterns on leaves

What is Variegation?

Many of the patterns you see on plant leaves, especially on garden and house plants, are caused by variegation.

Variegated leaves have areas of paler yellow or white on them, and vary widely form species to species, and between individual plants. Some variegated leaves even have dark red or scarlet areas. So what’s going on to cause these markings?

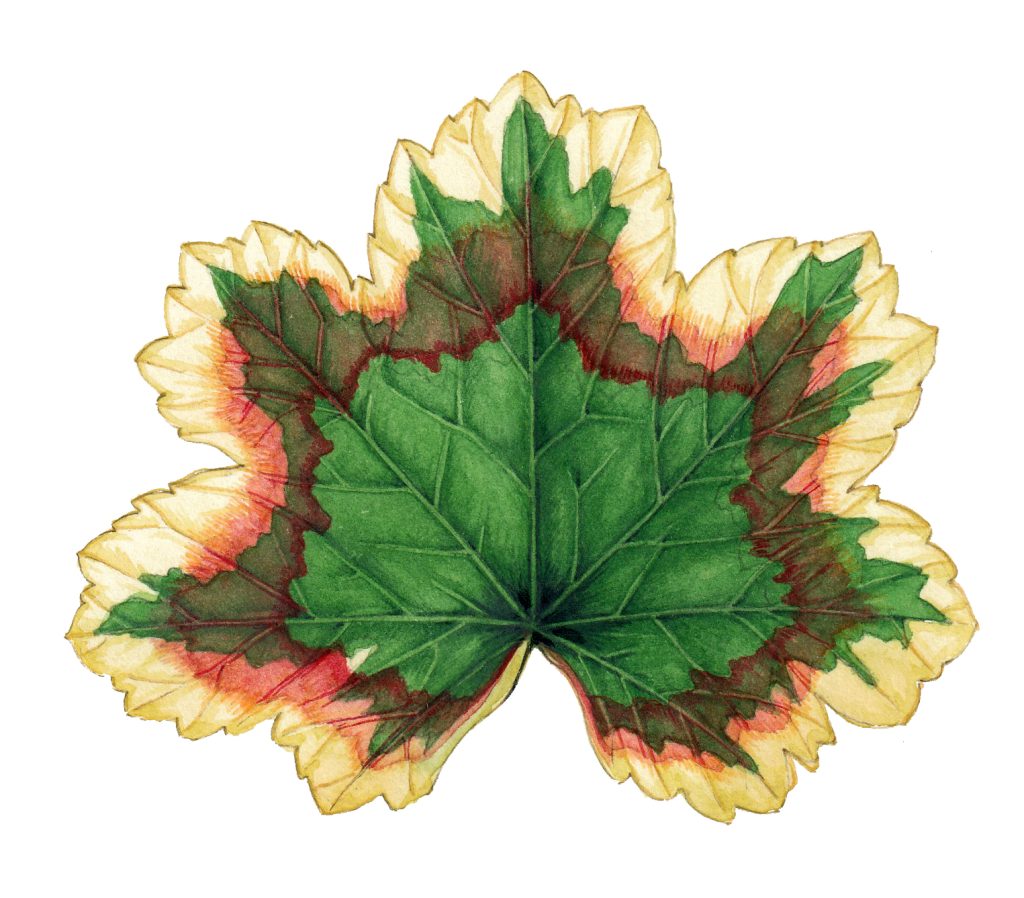

Variegated zonal geranium leaf Mrs Pollock

Variegation happens when cells in the leaves end up without plastid pigments, which normally provide the green chlorophyll we see in most leaves. This occasionally occurs in the wild, and can be triggered by too much cell oxidization. Without the green chlorophyll masking them, we see other yellowish pigments, or just the white of a colour-less leaf.

Variegation in the wild

It’s pretty rare in the wild because leaves that aren’t full of chlorophyll can’t photosynthesize properly. This means they can’t produce the sugars the plant needs to survive.

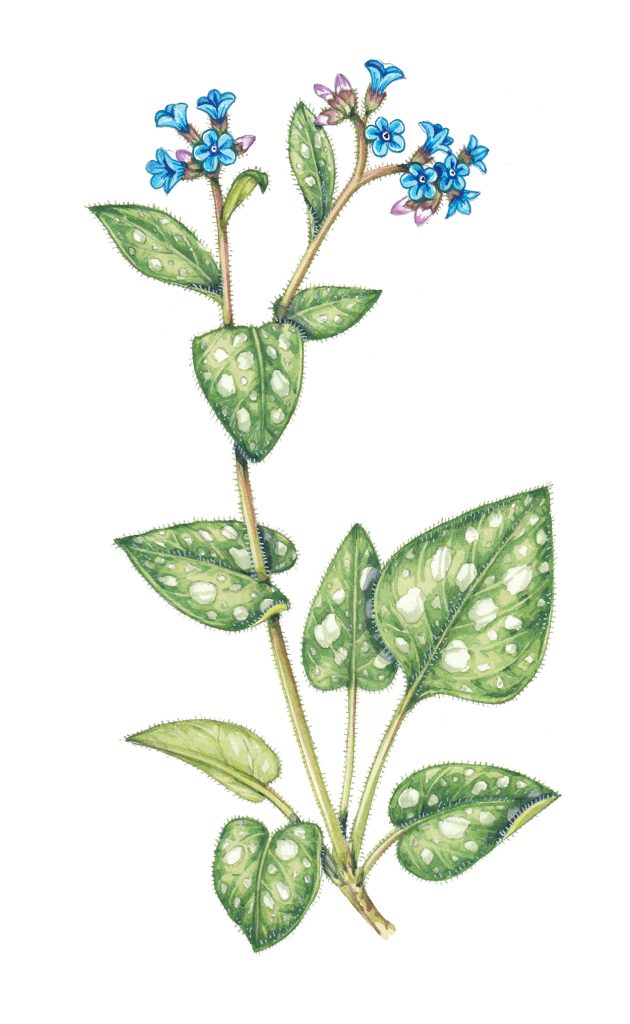

Wild cyclamen Cyclamen hederifolia, Lesser Celendine Ficaria verna, Lungowrt Pulmonaria officianalis and Milk thistles Silybum do show variegation.

Cyclamen hederifolia sketchbook study

Variegated patches might help protect leaves from UV rays, help in pollination and seed dispersal, and be used to keep a plant’s temperature stable (Thermal Benefits From White Variegation of Silybum marianum Leaves. Shelef, 2019)

Lungwort Pulmonaria officinalis

Variegated Houseplants

Variegated garden and house plants are much more common. They originally come from cuttings of wild plants, and are propagated over the generations because of their pretty leaf markings.

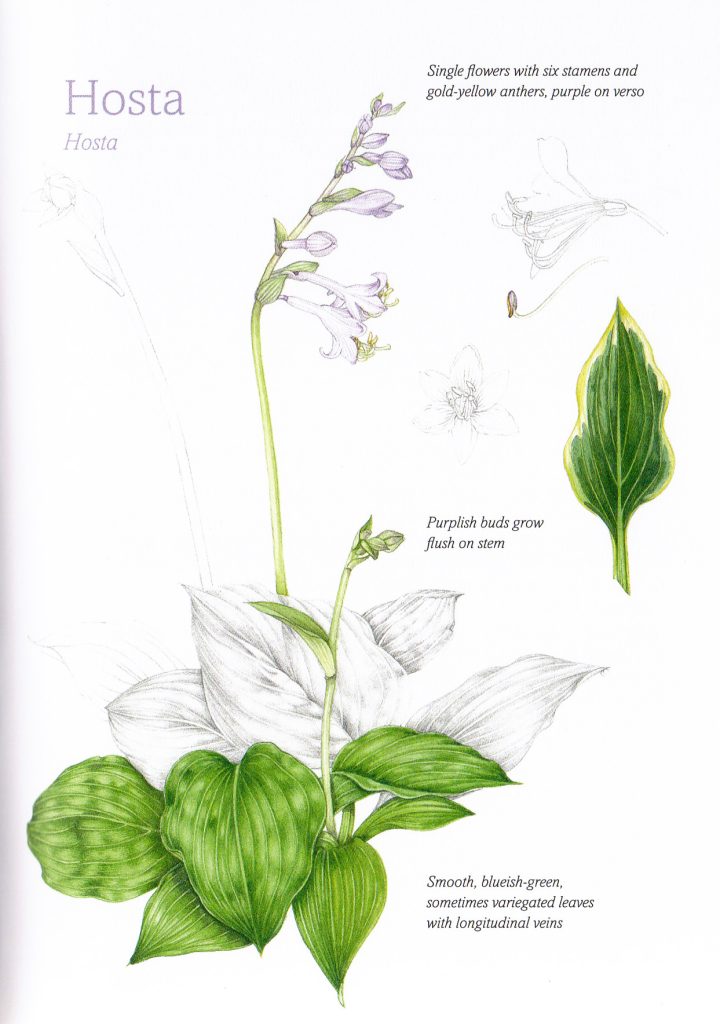

Hosta showing variegated leaf on the right (from The Garden Forager by Adele Nozedar)

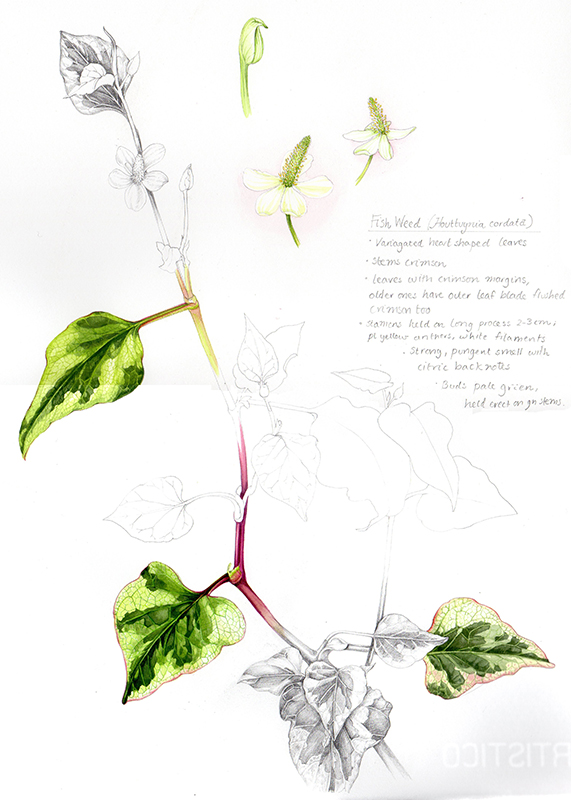

You can get variegated forms of tons of common plants; hollies with white leaf margins, big waxy hosta leaves striped white, Hebes edged with cream, Geraniums with rings of colour on their leaves, Periwinkles Vinca, Salvias, Yuccas showing sword like striped leaves, big leaved rubber trees Ficus, Peace lilies Spathiphyllum, Calathea with their white blotches, Chameleon plants Houittuynia with leaves flushed crimson…the list goes on and on.

Chameleon plant Houttunyia cordata

Often these variegated forms originate from wild plants that come from plants from across the globe, and get planted wherever gardener’s want them, and conditions allow them to grow.

Reverting to the wild

However, if you put them in shaded and nutrient-poor parts of your garden, they’ll often revert to having green leaves as they struggle to produce the energy they need. If you try to grow variegated plants from seed they too will mostly revert to type. Having big blotches on your leaves that can’t produce sugars is not efficient, so in most cases (and certainly in temperate climates where water loss and sun damage aren’t big issues) plants will avoid variegation unless conditions are so good they allow the luxury of having inefficient foliage.

Types of Variegation: Blister

There are different forms of variegation. Some leaves will have blotchy white marks as a result of damage cause by mosaic viruses. These tend not to be propagated or grown by gardeners.

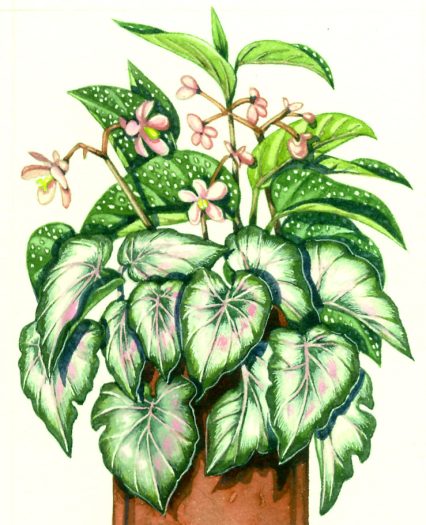

Blister variegation happens when there are little air bubbles between the surface and the body of the leaf. These look like white or silvery areas. This is what causes the pretty spots on Begonia leaves, and the stipes of the Aluminium plant Pilea cadierei Wild flowers with this variegation are few and far between; the spotty leaves of Lungwort, the variations on Cyclamen leaves, and the white areas on Milk thistle leaves (where these blisters follow the lines of the leaf veins) come to mind.

Begonia Begonia pearce

Why use Variegation?

Some researchers have suggested these blotches might be a form of mimicry, making the plant look like it had already been attacked by leaf-miners. Leaf miners looking to lay their eggs would avoid such a plant, so the trade off between not being eaten and not being able to produce sugars in the white blotches paid off. (Leaf variegation in Caladium steudneriifolium (Araceae): A case of mimicry?, Soltau 2009)

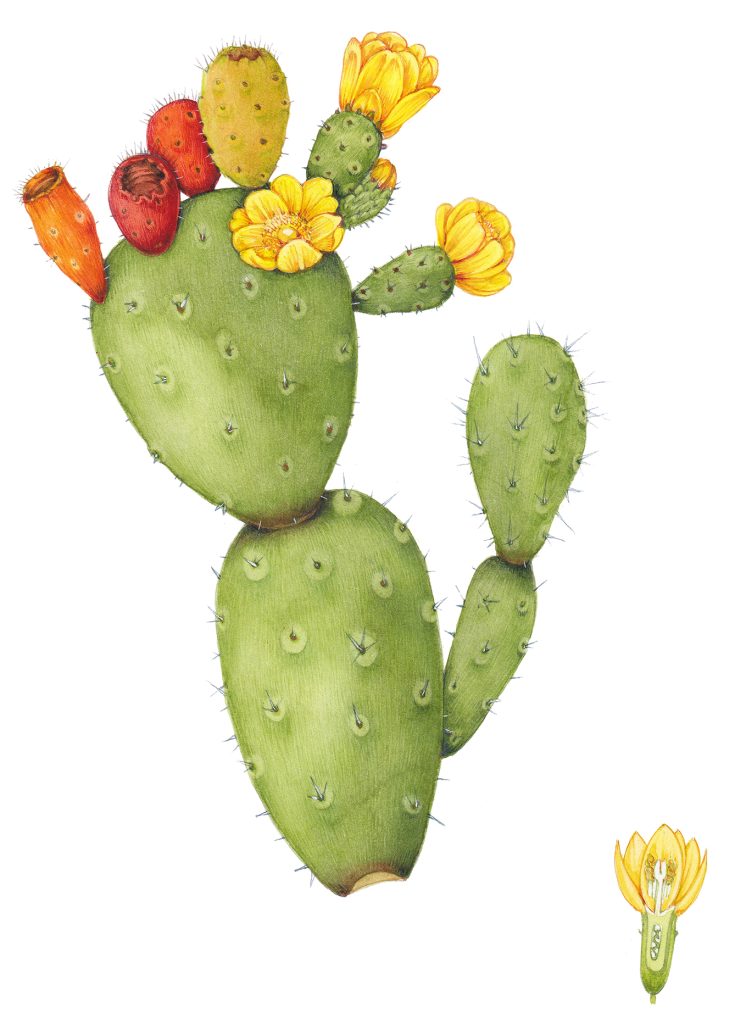

Another suggestion is that white spots, stripes and blotches could act as a warning to animals thinking of eating them. Lots of cacti, Aloes, and Euphorbia have impressive spines and these markings. (Aposematic (Warning) Coloration in Plants Lev-Youdun 2009)

Prickly pear Opuntia ficus-indica

In hot climates, the white areas of variegated leaves may help handle the fierceness of the sun, and with water retention. It’s no surprise houseplant cultivars come from these regions.

Types of Variegation: Pigmentary

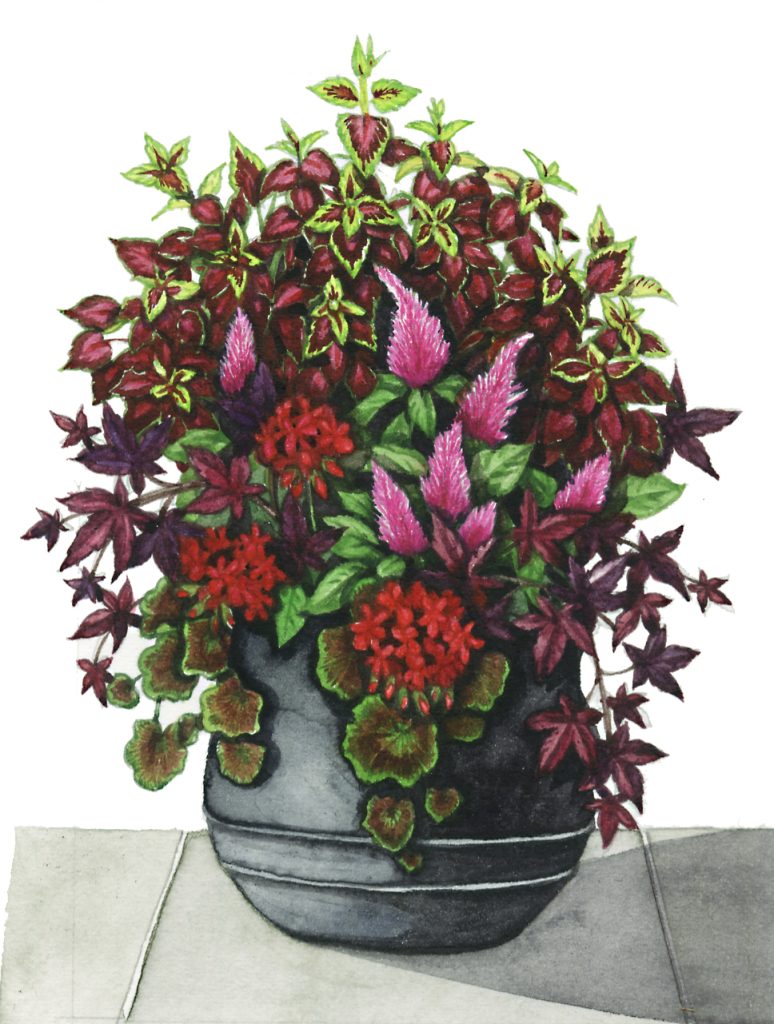

Pigmentary variegation happens when a leaf has areas without chlorophyll; or with another, stronger pigment such as anthocyanic (which cause pink and purple colours). The Coleus houseplant is a good example of this, bright green leaves blotched with pink areas, then a darker purple where the two pigments overlap.

Coleus and other red-flushed plants

In wild flowers, one of the commonest plants to show this effect is the clover. Look closely at a Red clover leaf Trifolium pratense. There are much paler areas on each leaf, like arrow-heads. These are distinct and occur on most of the plant’s leaves.

Red clover Trifolium pratense

You can mostly tell if a leaf is variegated, or if the blotches are caused by a deficiency in some nutrient or mineral. The edges of variegated areas are sharply defined, and an individual leaf will not re-gain its’ green-ness if you change the soil conditions. It might start growing new leaves which aren’t variegated, but leaves which are variegated remain so through their life – the missing plastid pigments can’t re-grow.

Autumn leaf colour and Variegation: The same source at work

It’s worth remembering that this effect, the lack of green chlorophyll, is exactly the same as what happens in autumn. Leaves are normally green, but chlorophyll is broken down by deciduous trees as the colder weather approaches. The risk of damage outweighs any benefit a tree may get from keeping hold of photosynthesizing green leaves through winter.

Sycamore leaf Acer pseudoplatanus

What’s left? The other pigments, many of which have been there round. Yellows remain, caused by carotenoids and flavonoids (including one, lutein, which is what makes egg yolks golden!). Oranges caused by other Carotenoids like beta-carotene (which also give carrots their colour) also remain.

These do get broken down as winter comes, but far slower than the chlorophyll. Around now, trees also start producing the reds of anthocyanin. Surprisingly, even now no-one really knows why this red pigment appears so late on in leaves, some suggest it might be protective.

Conclusion

Although variegation in the wild is not unheard of, it’s unusual because of the biological cost. This isn’t true for house plants, hence the amazing variety of leaf colour we see.

Understanding what causes variegation also helps us know more about the chemistry and botany of leaves, which (one hopes) will end up with us admiring then even more.

Fascinating stuff, Lizzie, thank you! Funnily enough, I’ve just begun researching variegation for a painting of my own, you are way ahead of me! I did hear of one unusual plant, a honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica ‘Aureoreticulata’, which has yellow lines on its veins – very unusual in that its variegation is caused by a virus, but is stable. There’s supposed to be one at Hilliers but I haven’t managed to find it yet.