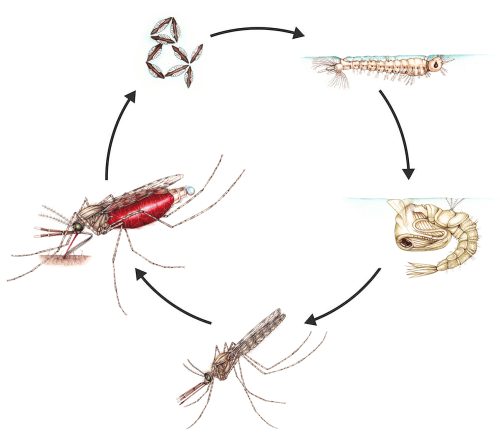

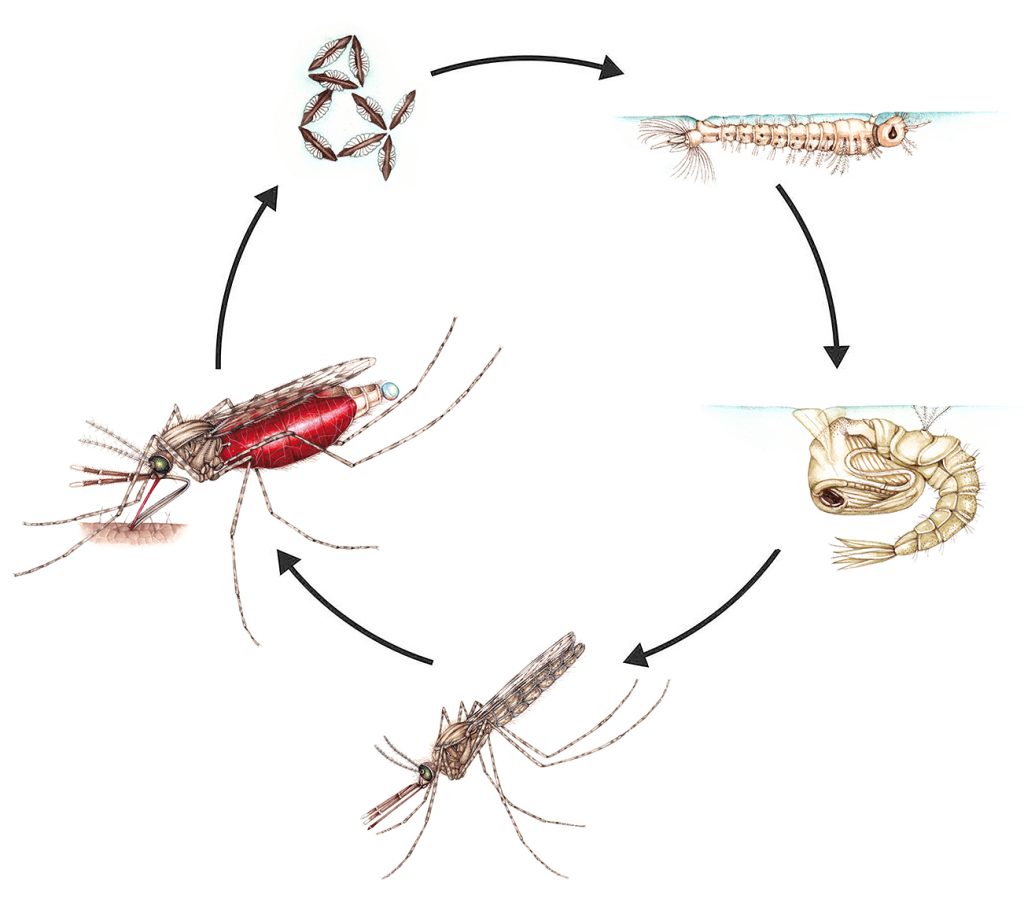

Mosquito life cycle – illustrating the Anopholes mosquito

Introducing the African Malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae

The mosquito is one of the most loathed of all insects, partly because of the itchy bites they cause, but also because of their deadly role as vectors for disease, especially malaria. In 2021, according the the WHO World malaria report, there were 247 million cases and 619,000 deaths from malaria. In the past I painted a quick (slightly unsatisfactory) sketch of a mosquito. However, it’s a subject I’ve been wanting to return to for many years, and recently I’ve managed to find time to illustrate a life cycle based on Anopheles gambiae, one of the most efficient spreaders of the most lethal strain of malaria. Throughout researching this blog, I found the pages on Malaria from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) invaluable.

Previous mosquito sketch

Problems and caveats

I’m not an epidemiologist, or even an entomologist. I found, during research, a lot of information on Anopheles mosquito species, although not an enormous amount on differences between the species. Much of it is very technical. So although the life cycle I’ve illustrated is accurate for an Anopheles, I can but hope it’s more relatable to Anopheles gambiae than to other similar species. I also flirted with the idea of including the life cycle of the Malaria-giving parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. But the amount of detail required to do it justice (it has two hosts and goes through a whole gamut of different life stages) means I’ve had to shelve it for a rainy day. (For more on the Plasmodium parasite life cycle from Research Gate, click here.)

What is a mosquito?

Mosquitoes are flies, members of the Diptera. They’re cousins of the midges (Chiromonidae) and crane flies (Tipula). Visually, they differ from the similar-looking gnats and midges in the angle at which they hold their legs, Chironomids holding them forward, mosquitoes holding them outward.

Chironomid midge adult Micropsectra radialis

In defence of mosquitoes

Please bear in mind that the vast majority of mosquitoes are not killers. Only some of the known 3,500 plus species of Culicidae (Mosquitoes) feed on blood, of those only some target mammals (including us humans). Most blood-feeders take blood from other mammals, some from birds, and even snakes can be the chosen prey. In fact, some of the large Toxorhynchites mosquitoes feed on other mosquito larvae!

Only female mosquitoes take blood meals. Males feed on nectar from flowers, and fruit juice. So do females, unless preparing to lay eggs. Although you may encounter male mosquitoes, buzzing and whining, they are incapable of, and have no interest in biting you. (You can tell male mosquitoes as they tend to have far more elaborate and feathery antennae than the females.)

In defence of female mosquitoes

Even female mosquitoes need to be better understood. As with every living thing, they’re not out to get us, or planning to give us disease. A female needs a blood meal in order to fully develop and lay her eggs. She may well only take one big blood meal, and that may be at one sitting. Repeated bites happen when she’s consistently interrupted, having to return over and over again to her meal. It’s rather like a human being taken away from a pizza mid meal. Then having to start the whole procurement process from scratch each time you try to have another bite.

And as for being a vector of disease, again, this is highly unfortunate for us, but in no way an evil master plan of the insect. In fact, the Falciparum parasite damages mosquitoes too, compromising their gut lining and having to evade the immune system of these dipterans (PNAS Vol. 112 No. 5)

I know I’m fighting a losing battle here, and the havoc, damage and heartbreak caused by Malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases is absolutely massive. I’m just pointing out that only some mosquitoes cause these illnesses, and many are harmless pollinators. I think that as a whole, they deserve respect, and a kinder reputation.

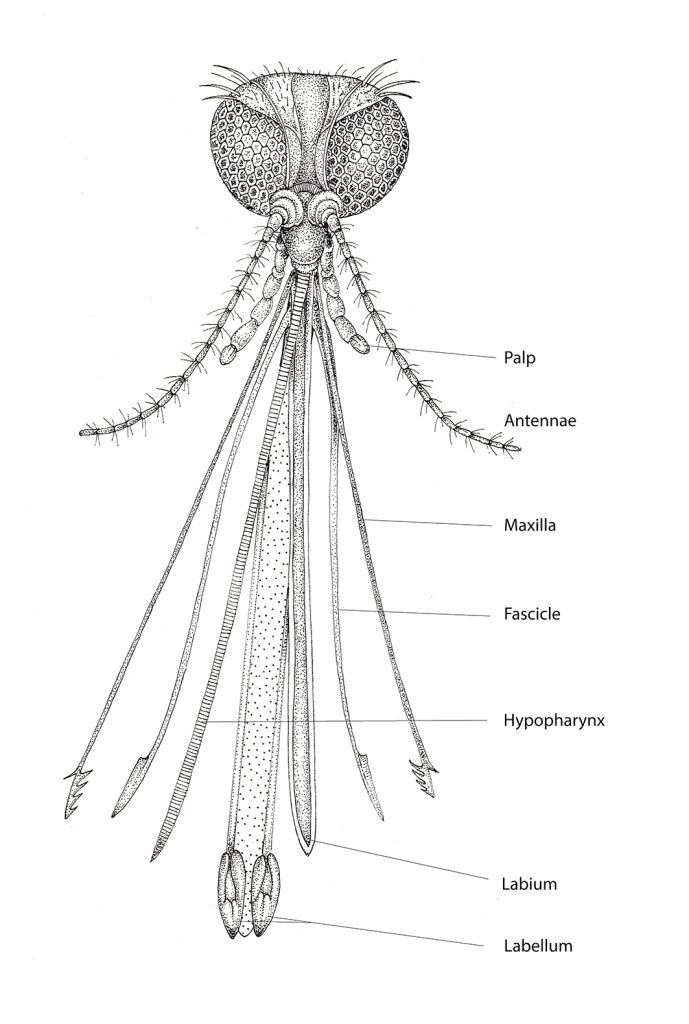

Pen and ink diagram showing the amazing feeding equipment of a female mosquito

To see footage of the mouthparts of a feeding mosquito in action please check out this NPR video.

Anopheles: One Genus of Mosquito

Anopheles, the genus I’m illustrating and the one responsible for malaria, are Marsh mosquitoes, They are one type of these biting fly; others are the Culex and Aedes. Although all three are able to carry disease, injecting directly into the bloodstream, only Anopheles can transmit malaria. Even more specifically, of the 460 known Anopheles species, only 100 can give humans malaria. Of these, only 30 or 40 carry the most lethal form of the disease, Plasmodium malaria. And of these, it’s only the females who can infect you, as they’re the only ones that feed on blood. (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).)

Life cycle of Anopheles gambiae

Other mosquito genus: Culex

Culex are also vectors for disease, although not malaria. They can carry West Nile virus, Japanese Encephalitis, and Elephantisis. None of these is pleasant, and all can be fatal. Unlike our Anopheles, their eggs are without floats (although laid singly). Larvae hang down at an angle from the water surface with their long breathing tufts breaking the meniscus. Pupa are similar to Anopheles and Aedes species. The adult females hold their proboscis at an angle to their bodies (rather like in the first illustration in this blog).

Other mosquito genus: Aedes

Aedes mosquitoes carry Yellow fever, Chikungunya, Zika fever, and Mayaro. They’re easy to spot thanks to very striking black and white striped legs. They also have a marking a bit like a harp on their thorax. Again, only the females are disease vectors. Aedes lay their eggs in a mass on the water surface, not singly. Their larvae are like Culex, hanging down at an angle from the water surface and breathing with a tufted breathing tube (longer than the Culex species). Pupa are similar to Anopheles and Culex. Adults hold their proboscis at an angle to their bodies, which is similar to Culex species. However, they tend to stand higher on their legs than Culex. They may also lift their rear legs up.

Anopheles gambiae

This mosquito forms the basis of my mosquito life-cycle. According to the CDC, “Anopheles gambiae is the most efficient vector of human malaria in the Afrotropical Region (CDC 2010). Thus, it is commonly called the African malaria mosquito.” And this is why it’s my mosquito of choice. It lives in a band across the African continent, throughout sub-Saharan Africa and up to areas of southern Arabia.

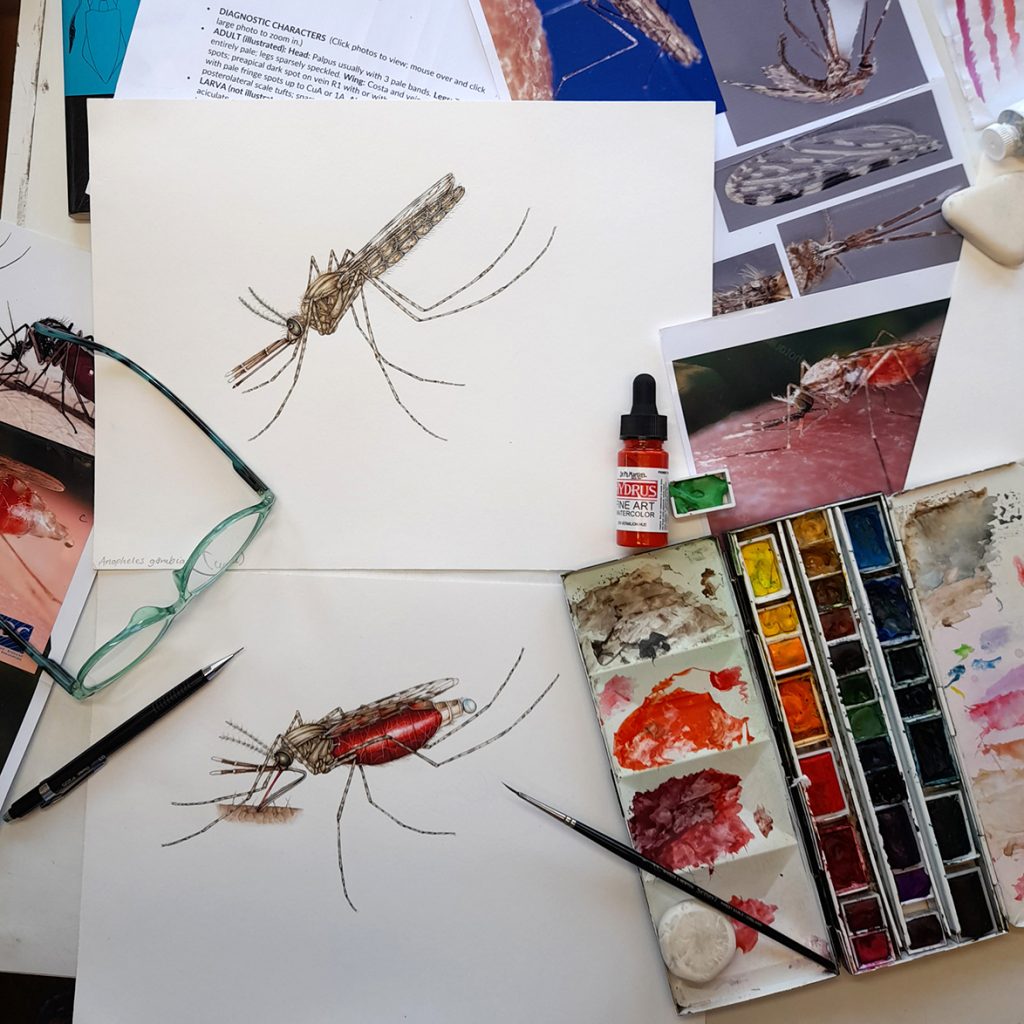

Unfed female mosquito with paints and reference

The main features that distinguish it from other Anopheles relate to placement of hairs on the larva, and a greenish hue to the pupa. Adults have pale bands on their palpus (mouthparts), spotted wings, and sparse speckling on their legs. The abdomen doesn’t have little hair tufts on its sides (postlateral scale tufts). There are often no abdominal scales on the mosquito back; if they are present they’re small. For a splendid overview of mosquito morphology, please see the pdf from Nathan Burkett-Nadena of Florida University’s Entomology department.

Details of the life cycle of A. gambiae come from the University of Florida’s “Featured Creature: African Malaria Mosquito”; and the Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit.

Life cycle of A. gambiae: Eggs

Eggs are laid on the surface of clean water, in batches of 100 – 250. Each one is laid singly, not as a raft. Each is boat shaped, slightly domed, and supported by a system of lateral floats. They’re brownish in colour and are about 0.5mm in length. Eggs hatch after 1 or 2 days into free swimming larva.

Eggs of A. gambiae, seen from above

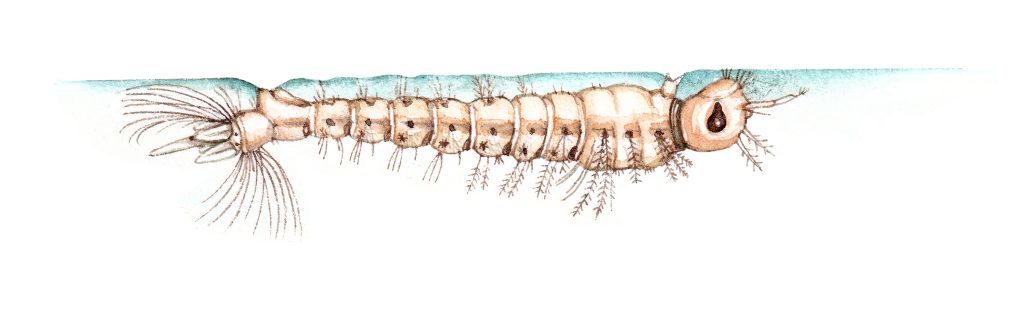

Life cycle of A. gambiae: larva

Larva grow from their first stage, after hatching, into a final size of 5 – 6mm long. They moult repeatedly as they grow, passing through 4 instar stages before pupating. Lying just below the water surface, they get oxygen through a rudimentary breathing tube which sits just before their tail end and a brush of hairs. This is true for all Anopheles species; their short breathing tubes mean they all assume this distinctive posture, parallel to the water surface. Other abdominal hairs help aid in floating. They feed on algae and organic matter, and can be seen wriggling in still water with the naked eye.

Larva of A. gambiae

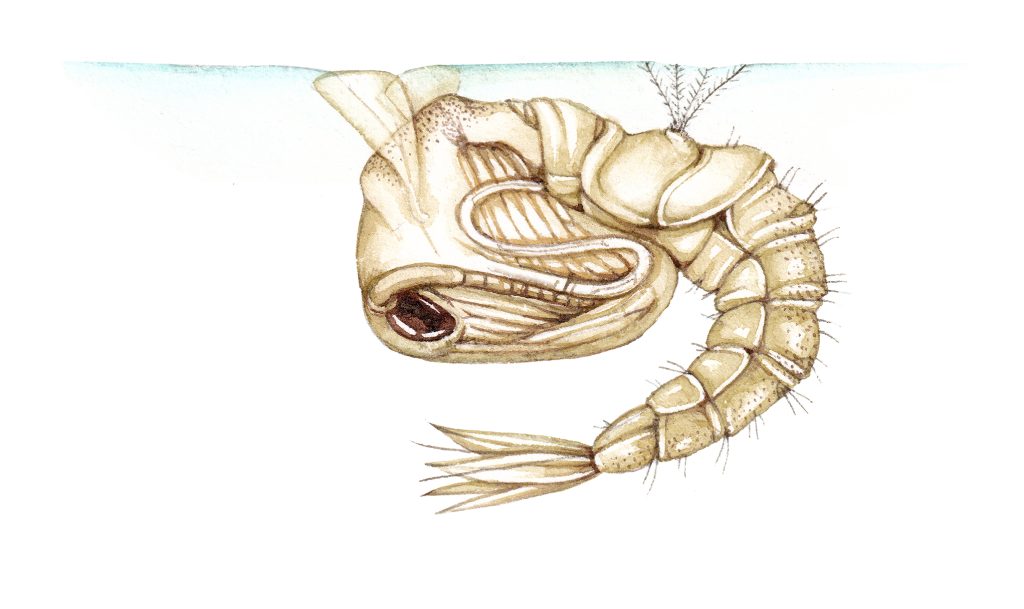

Life cycle of A. gambiae: Pupa

Comma-shaped and tending to rest at the surface of the water, all mosquito larva look similar. They have a large cephalothorax (combined head and thorax) which is clear, or slightly coloured. Their abdomens are segmented and thin, terminating in a tail fin. They use this to rapidly swim away and escape when disturbed, which is an unusual ability in the (normally static) pupal form of an insect. A tuft of hairs at the beginning of the abdomen helps the pupa stick to the water surface. You can see the antennae and limbs growing within the cephalothorax, and eyes are large and obvious. Pupa breathe with a pair of respiratory trumpets which project from the back of the cephalothorax, into the water meniscus. They do not feed in this stage, which lasts another 2 – 3 days.

Pupa of A. gambiae

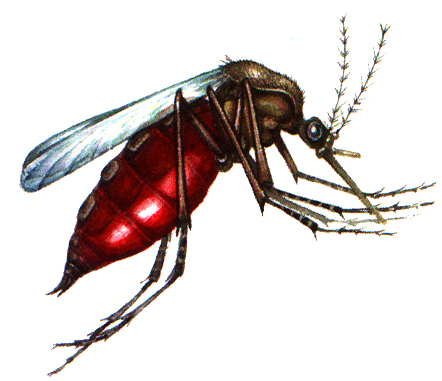

Life cycle of A. gambiae: Adult female

I’ve chosen to illustrate the female in unfed and in feeding poses. This is to show the massive difference that a good blood meal can make to the mosquito’s appearance. After a meal, the abdominal plates are stretched and expanded by the contents of the gut. Before, the grey mottled markings are far easier to see. The mosquito is grey to pale brown, dotted with pale yellow areas, cream-coloured scales.

Unfed female African Malaria mosquito

The unfed female has the typical angled pose of a resting Anopheles, with body held in a diagonal in line with the mouthparts. As with many mosquitoes, her legs are held aloft.

A. gambiae have distinctive dark wing patches. These occur at specific areas along each wing, which is tricky to capture in illustrations showing the wings folded and overlapping. Wing margins are fringed with small hairs. Being a smallish species, A. gambiae have wing span of about 3 – 4.5 mm.

Distinctive mottled wings of A. gambiae

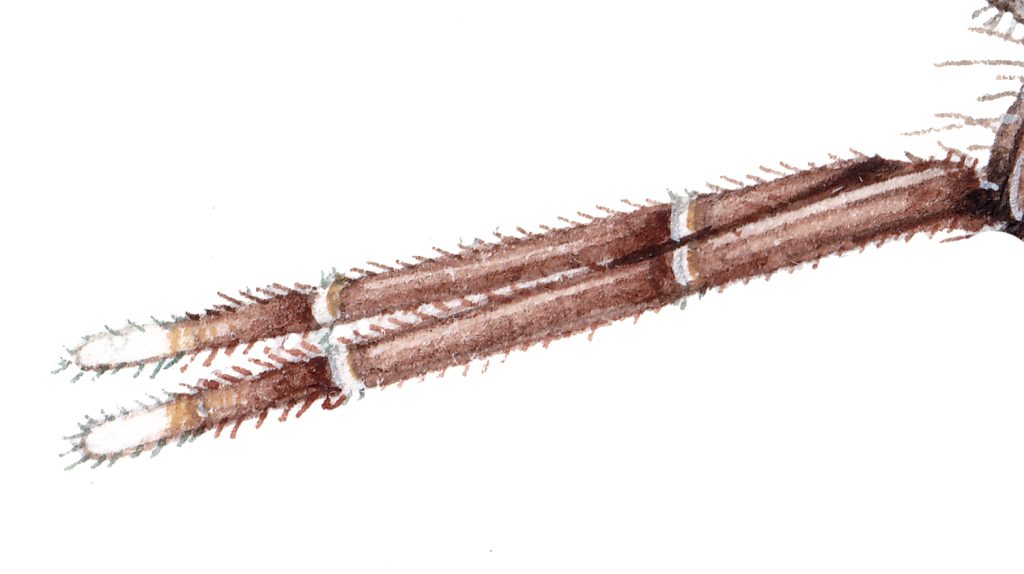

Another feature that helps identify this species is the striping of the palps, which are banded in a specific pattern and have white tips. These organs sense odour, so are pretty prominent in mosquitoes who use smell as one way to find their prey.

Palps of A. gambiae

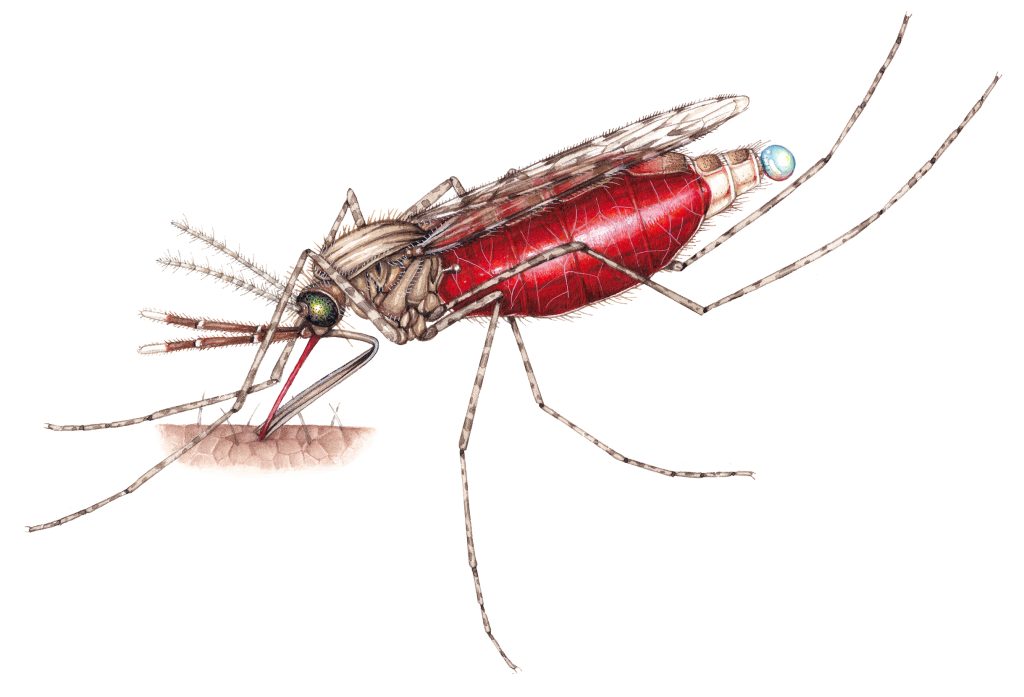

Life cycle of A. gambiae: Adult female and feeding

Mosquitoes are crepuscular and find their prey by sensing exhaled CO2, body temperature, and vibration. Evidence suggests humans with blood type O, who breathe heavily, are pregnant, or who have a heavy load of skin bacteria may be more prone to mosquito bites; although there are genetic factors at play too.

Anticoagulants prevent the blood from clotting as she feeds, and the itch we feel comes from out our immune system’s response – the production of histamines which lead to inflamation and itching.

Feeding African malaria mosquito

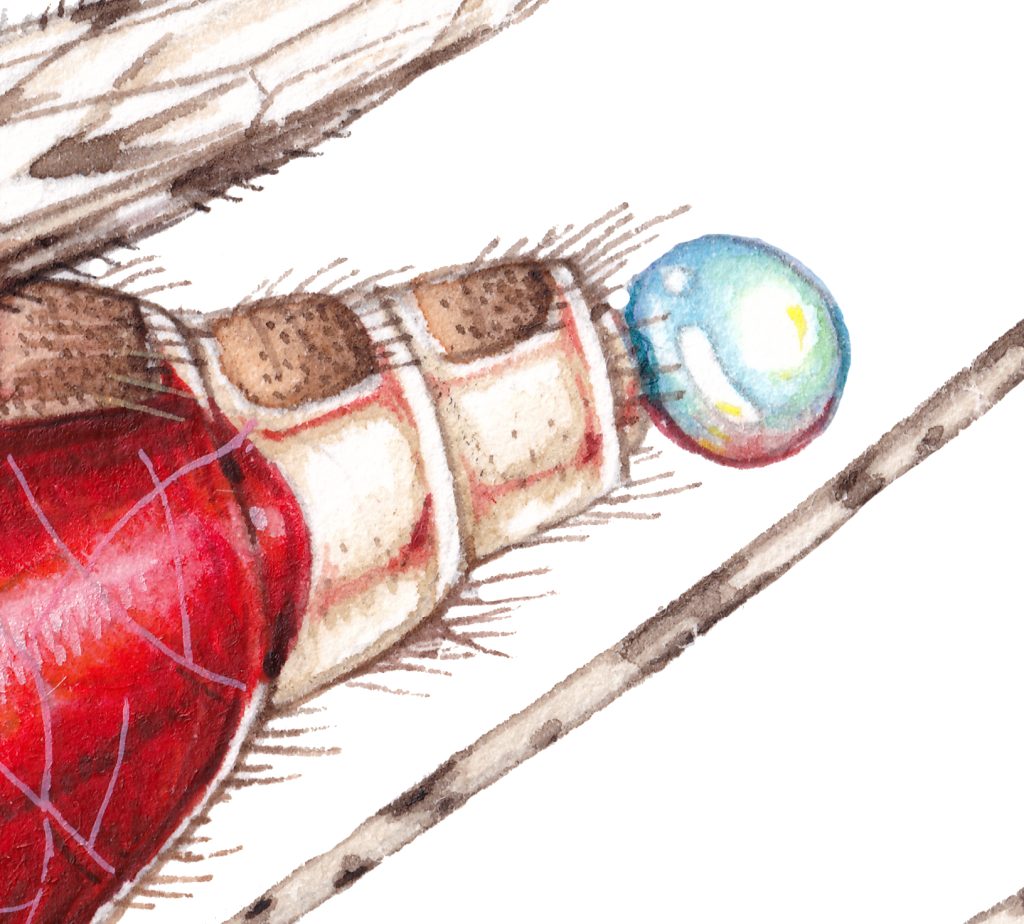

The fed female holds the same pose as an unfed female at rest, although they often lower their bodies closer to the horizontal when feeding or when weighed down with blood. The droplet at the tip of her abdomen occurs when excess water is exuded to make way for more solid parts of the continuing blood meal, but also has a role to play in reducing body temperature via evaporation (Current Biology Lahondere & Lazzari 2012)

Droplet of exuded water

Once fed, the female mosquito goes to digest her meal, laying eggs a couple of days later and thus continuing the cycle.

Conclusion

It’s no surprise that there’s an enormous amount of information on mosquitoes and malaria online. Wading through it has been a delight as well as a headache. and the temptation to fall down endless fascinating rabbit-holes relating to disease prevention and control, or to the mechanisms of the mosquito mouth parts, has been hard to resist. I nearly got diverted by Plasmodium falciparum, which I swear I remember illustrating for a project at college.

Completed mosquitoes with some reference and art materials

However, I’ve tried to retain focus, and stick to Anopheles gambiae. How it lives, what it looks like in its’ different life stages, and why it matters to us as humans.

For a good spring board, if you want to learn more about mosquitoes, you could do worse that check out the Wikipedia entry on mosquitoes. And that’s not something I say every day.

I hope you’ve enjoyed visiting these biting flies with me, and haven’t ended up feeling itchy or listening out for that high-pitched and un-mistakable whining sound…

Illustrating the mosquito compound eye

Hi Lizzie! Such beautiful work, I’m admiring your art from all the way down under in Australia. Thanks for showing close ups or your illustrations. I’m curious about your process – have you drawn each element onto separate bits of paper and then scanned them for their final placement into the diagram? Hoping to be as skillful as you someday!

Have a great day 🙂

Cheers, Naomi

Hey Naomi, thanks for the question. I painted both adult females on separate sheets of paper, and the other stages in a column of a third sheet. Scanned separately, they were then organised into a cycle arrangement. Almost the hardest part of the whole process was finding and using a decent set of arrows! So yes, your guess was right. And keep at it, anyone can paint like me if they’re able to put in the hours. x

Good evening Lizzie, once again apart from your illustrations which are really good I find myself investigating Mossies !!!!

Regards Peter

Thanks Peter, so good to hear you’re keen to look at mosses now

x

Lizzie Harper’s blog on the mosquito life cycle is both informative and eye-opening. Her honesty about the challenges she faced in researching and illustrating this complex topic adds a relatable touch to her work. The distinction between various mosquito species and their roles in transmitting diseases like malaria, West Nile virus, and Zika fever is crucial knowledge. Harper’s illustrations vividly capture the stages of Anopheles gambiae’s life cycle, making it easier for readers to understand the mosquito’s biology. It’s a reminder that not all mosquitoes are disease vectors, and many play vital roles in ecosystems worldwide.

Thank you for this wonderful over view of Mosquito life cycle.

Please can I get citations and references to it.

Hi Akpoke. It’s based on lots of research from many sources. If you’re interested in using it, please email me on info@lizzieharper.co.uk with some details of how you’d like to use it and I’ll get back to you. So glad you like it! lizzie