Trees: Rowan

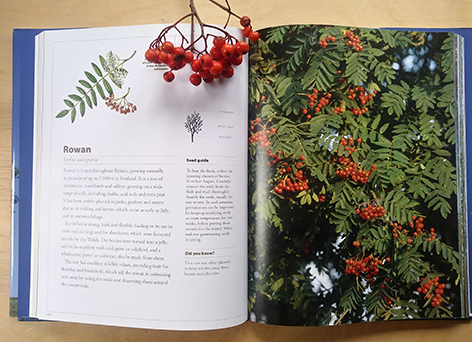

Trees: Rowan is another blog inspired by my illustrations for “The Tree Forager” by Adele Nozedar, published by Watkins. It’s inspired me to have a look at some of my favourite trees. The Rowan is another in this series, along side the Sycamore, Ash, Hawthorn, and the Oak.

Rowan Sorbus aucuparia is a small tree, but one which gives an enormous amount. Prodigious blossom in spring, vibrant orange berries in autumn, and a whole to offer in terms of history and folklore. And you can make jam from its berries!

Not only does the Rowan provide all this, but it can also grow in really tough environments. It’s not called the Mountain Ash for nothing, and you frequently see lone Rowan trees clinging onto rocky outcrops in upland and heathland habitats.

Rowan berries and illustration

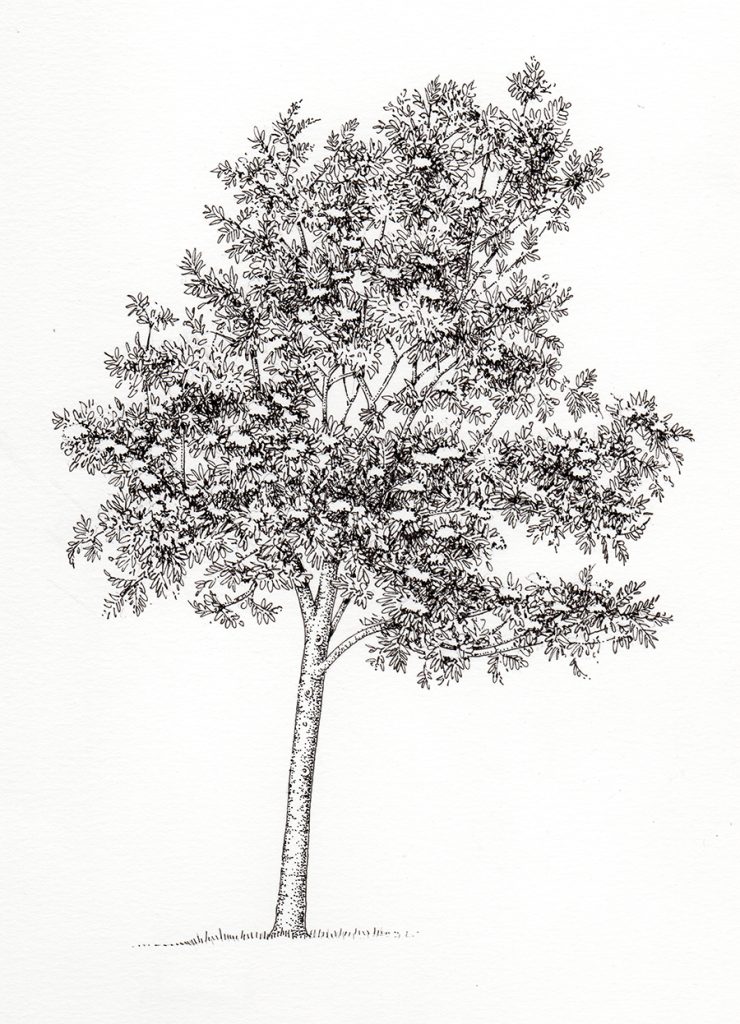

Identification: Tree shape

Rowan is a small and slender tree. It normally grows to 10 – 15m tall, and can live to 200 years old. Rowan grows swiftly, and is found up to 2000m in the Alps – it can tolerate the cold.

It can grow in really unusual places. I’ve seen Rowan trees growing perched on top of boulders. They grow on the sides of streams, from crevices in cliff faces, and much further north than many other deciduous trees. Rowan even help make up the Boreal forest, which creeps to the edge of the Arctic.

Despite their seeming predilection for odd places to grow, these sites tend to dovetail with places where large grazing herbivores can’t browse.

Rowan tree in blossom

Although this blog is about the common Rowan, there are 44 species and 8 hybrids of this tree in the UK. Many can be found in the Avon gorge, in Bristol. In fact, this habitat has the greatest diversity of Rowan species in the whole of Europe, and many are very rare indeed.

Because of the blossom and attractive berries, Mountain ash is often found in gardens, as well as across the countryside.

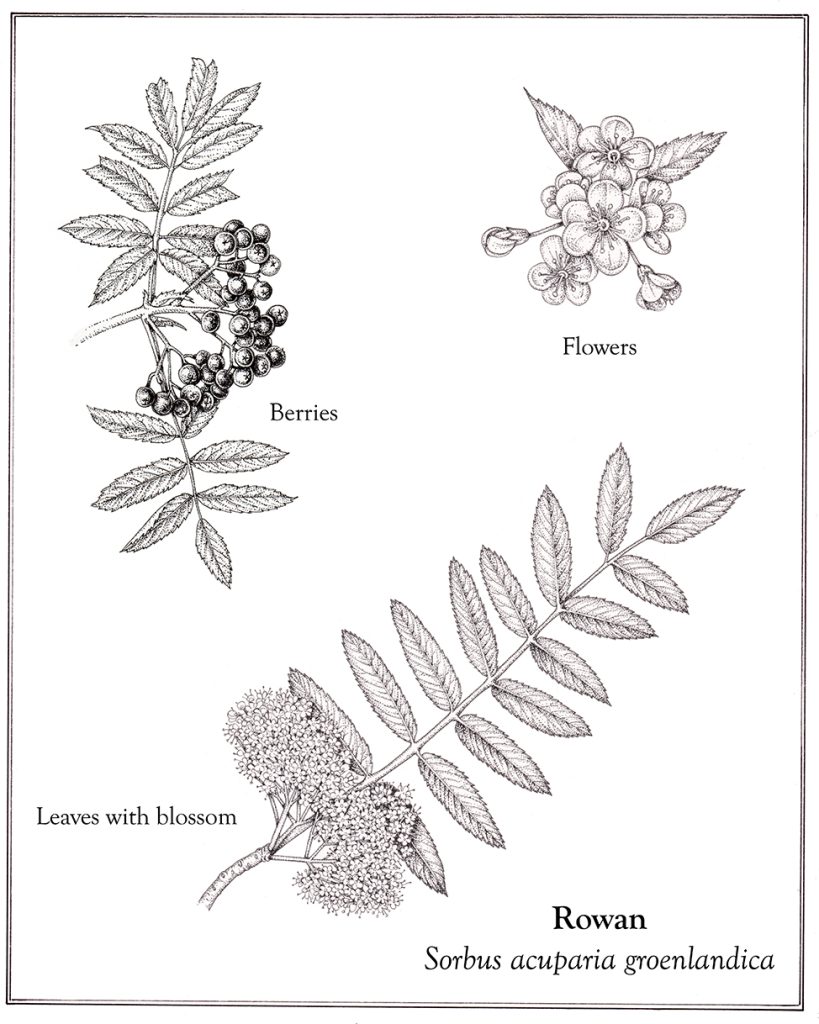

Identification: Leaves

Rowan leaves are compound and up to 20cm long. This means that each leaf is made of lots of smaller leaflets. Each rowan leaflet is oblong, and has sharply toothed margins (for more on leaf margins see my blog). There will be a lone leaflet at the tip of each compound leaf; all the others are paired and opposite one another. There are 5-7 pairs per leaf.

Sketchbook page of Rowan

Leaves are a dull green on top, and many be slightly pubescent below, especially when young.

Identification: Flowers

In spring Rowan is awash with frothy white flowers that are strongly scented. The whole tree buzzes with the bees and flies, amassed around the blossom.

Each flower is 8 – 10 mm across, and has 5 creamy rounded petals. Rowan is a member of the Rosaceae family, so you may notice a family similarity in shape to apple, pear and plum blossoms (although each flower of the Rowan is much smaller).

Rowan flowers have male and female structures, and are hermaphrodite. There are 3 – 4 styles, and lots of prominent stamens bearing cream coloured pollen.

The blossoms are borne in domed clusters 8 – 15cm across. From a distance these look like a froth of cream flowers. There can be up to 250 flowers per flowering head (or corymb).

Detail of Rowan blossom

As well as bees and flies, Rowan blossom is an important source of nectar for hoverflies and beetles.

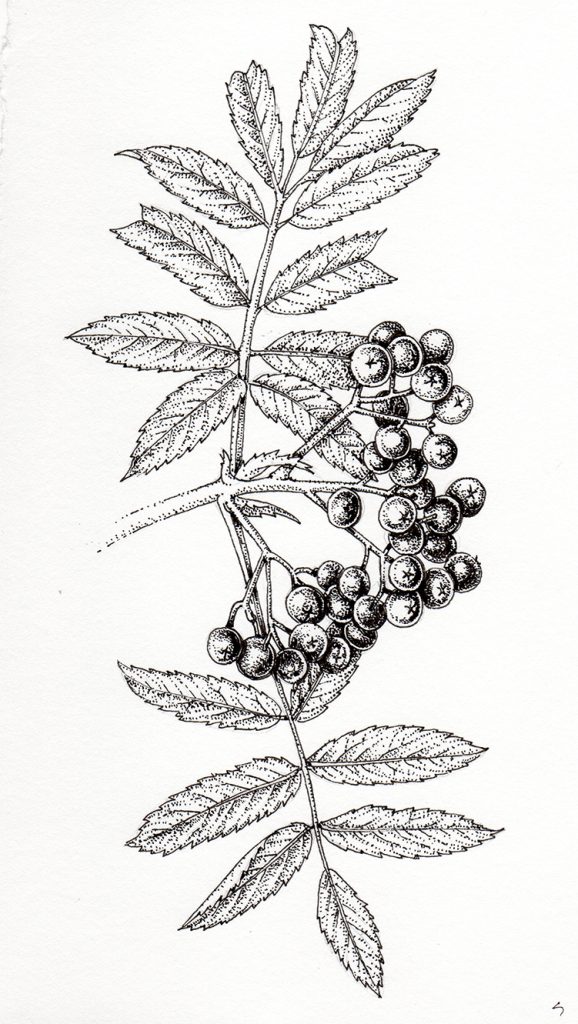

Identification: Fruit

Autumn sees the tree produce vibrant orange berries which glow against a deep blue sky. they can also be used for jams, and are important for wildlife.

Late autumn, and the leaves turn gold and brown, contrasting with the remaining berries.

Each berry is oval or round, and up to 8mm across. You sometimes see inconspicuous lenticels on the berries. There are up to 8 seeds inside each berry, although 2 is the norm. Trees begin to produce seeds from about 15 years old.

Rowan berries

The berries can vary in colour from yellowish to a vibrant red, but a rich orange is the most common colour. They’re shiny.

They’re very rich in vitamin C, in the form of ascorbic acid, and provide a vital food supply for birds and occasional mammals.

Pen and ink illustration of Rowan berries

Berries need the cold to break down their tough outer coats, and cannot germinate unless they’ve been exposed to cold temperatures.

In mild climates, berries are produced every year. Where the weather is colder and harsher, Rowan trees will mast. This means that every few years all the trees will produce a glut of berries. In between mast years, very few berries are produced.

Identification: Bark

Bark of the Rowan tree is smooth and a slightly greenish grey, with dark lenticels scatted across it. It looks silver in certain lights.

Twigs are often slightly hairy, especially when they’re young when they feel downy to the touch. This wears off, and older twigs are slightly shiny and glabrous.

In winter, Rowan twigs are easy to recognize. The buds are purplish-brown, pointed, and downy.

Similar species

The orange berries and blossom are unlikely to be confused with other tree species. However, both the Ash and the Elder also have compound leaves. The leaflets of these trees tend to be less crisply toothed than Rowan, and the shape of each leaflet is a little blunter. I’ve written blogs on the Ash and hope to write one on Elder, do take a look.

Ash leaf – note that the teeth are less sharp and each leaflet is rounder than the Rowan

History: Folklore

The bright berries of Rowan mean it has a rich history of folklore. This colour was thought to be highly effective at fighting off witches, so Rowan trees were planted near houses.

In Celtic mythology, Rowan is considered the tree of protection. Runes were carved into the living trees (which may well explain the name “Rowan” as both words share the same root) , and stone circles with Rowans planted nearby were thought to be the site of fairy activity.

Rowan Berry, leaves and blossom

Twigs or Rowan were used to stir milk in the diary, in the hope that it would prevent the milk from curdling. In the barns, Rowan crosses would hang above livestock to provide some protection from disease and witchcraft. Amulets and wands were made from Rowan, and those who practice divining believe that Rowan is particularly good at finding water. It was common to carry a sliver of Rowan in your pocket for protection from enchantment, and sailors believed a boat with rowan wood on board could not capsize or harbour anyone who would drown.

Because you can make out a five sided shape if you cut a rowan berry in half, they were thought to be magical and have protective powers. This is the pentagram symbol, or “eleven cross”.

In Wales, Rowan were often planted in churchyards, and in Scotland is was anathema to fell a Rowan tree.

Illustrating Rowan berries

Druids thought Rowan acted like a gateway to another place (one assumes somewhere more spiritual than merely the next town up the valley) and would drink wine made from Rowan berries to get second sight. Or drunk.

History: Food & Medicine

Rowan berries are edible, but not particularly pleasant unless processed. They’re commonly made into wines, jellies, and jams.

If food was sparse, rowan berries could be dried and ground into a flour which could be baked into a rudimentary loaf of bread.

Medicinally, Rowan has had many uses. It’s a cure for digestive complaints. It can be made into a poultice to treat ulcers. As a gargle, it can take on sore throats and tonsils. The high vitamin C content meant it was a splendid antidote to scurvy. It was used to treat sores, and to stop bleeding.

This is no surprise, Rowan in very rich in antioxidants which are used in modern medicine to treat everything that needs a boost to the immune system.

Uses

As well as all the protective, spiritual and medical properties, Rowan had and has practical uses too.

Its wood makes excellent handles for tools and utensil, and has a fine-grain. Henry VIII reckoned the Rowan made such good bows that he passed a law prohibiting people from using the wood for any other purpose.

The wood can also be used for wood turning and engraving blocks.

The whole tree is rich in acid and is highly astringent. This made it perfect for tanning leather.

The bark can be made into a black dye.

These days, a derivative from the Sorbic acid found in Rowan has been made into a food preservative which can eradicate nasty bacillus such as Clostridium botulinum. This bacteria can produce toxins that can cause botulism if ingested. These toxins are, according to the NHS website “some of the most powerful toxins known to science. They attack the nervous system (nerves, brain and spinal cord) and cause paralysis (muscle weakness)…if left untreated it [Botulism] can be fatal in 5 – 10% of cases”

Bohemian Waxwing Bombycilla garrulus on Rowan

The berries are wonderful for wildlife, with members of the Thrush family particularly fond of them. Redwing, Thrush, Blackbirds and Fieldfare all feast and help disperse the seeds. Dormice, foxes and pine marten also eat the berries

The leaves are eaten by caterpillars of the Welsh wave moth and Autumn green carpet. Apple fruit moth feast on the berries. Other moth caterpillars will feast inside the leaves, as leaf miners. Mountain hare eat young leaves; and red deer graze on the tree foliage, stems and tree trunks.

Threats

Rowan trees, like all UK species, suffer as a result of habitat loss. However, there is no immediate horrible threat, such as Ash die-back, knocking at the door of this beautiful tree.

They can suffer from fire-blight, European mountain ash ringspot-associated virus, and silver leaf disease.

The main threat to the Mountain ash is browsing from red deer and other large herbivores.

Rowan illustration in “Trees and How to Grow them”

Conclusion

Rowan, or the Mountain ash, is a common tree in the UK. The blossom and berries make it decorative and easy to identify. It’s uses stretch into myth, food, herbalism, agriculture, and legend. It’s an extremely important tree, not only in terms of wildlife and ecology; but equally for the role it’s played in human history and folklore.

Luckily, this is one of our trees which isn’t likely to be going anywhere soon. When I look at the blackbirds glutting themselves of the rowan berries in my garden, I’d very glad to know that.

Online sources for this blog include websites of The Woodland Trust, Trees for life, the Green Parent, and Naturespot. Book references for this blog include the excellent The Greenwood Trees by Christina Hart-Davies, and the Reader’s Digest “The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain” (out of print but commonly available second-hand).

There’s also a film of me illustrating rowan berries in real time, take a look if you fancy it:

I have never tried darks first. Now I’m enthused to give this method a try. I know we always are our own worst critics but you may have been a bit hard on yourself! They look splendid and you are an extremely good video teacher.

Hi Jeanie, thanks for the kind comments. Yes, dark to light just makes things a lot simpler, you need to hold much less information about what you’re looking at in your head at any one given point. Give it a go? It certainly isn’t for everyone, but I do enjoy working this way. Thanks again for the comment. yorus Lizzie

Thank you, very informative. Not just the painting, but the blog as well.

And thank you, too, Ineke. x

Always loved the Rowan tree. Recently bought three. Look forward to many years of pleasure from them. Your information has filled in many blanks in my knowledge. Well done, thank you

Oh how lovely! I adore our Rowan. It gives year long, and the birds love it. So glad my blog added to your knowledge. x

Thank you so much for this helpful and interesting demo. I thought the berries did glow.

Thank you, Laura! Glad it was helpful. x

I cannot get a straight answer to this question anywhere on the internet. I want to know if the compound leaves of the Rowan tree ***START OUT*** as one leaf and then separate into leaflets. Why can’t I get an answer to this? I recently had to have my precious Rowan tree removed. It broke my heart. But there seems to be a baby tree starting beside where it was. This baby tree has the typical Rowan leaf/leaflets but there seem to be some leaves that have not pinnated (sp?). I am wondering if these leaves ARE going to separate into compound leaves. Can you answer this? Thanks for any help you can give. These other leaves COULD possibly be another type of tree starting to grow right beside the Rowan.

Hey Joanne

If the leaves are growing right where your Rowan was then it makes sense that they would be growing from a sucker of Rowan, its something the trees do. The Rowan in my garden puts our all the leaflets from one leaf bud at the start of the season, and these enlarge (and the spaces between each leaflet enlarges) as the season progresses. Double check by going onto Google images and putting in “Rowan leaf bud”, lots of pics of early stage Rowan leaves come up so you can compare and contrast.

This article is truly inspiring and filled with valuable information. I love how clearly everything is explained. It really motivates readers to take action and learn more. Thanks for sharing such thoughtful and useful content with us sso id.