Trees: Ash

Trees: Ash

This is the third in my series on common trees, and this time it’s the Ash tree under the spotlight.

The Ash Fraxinus excelsior is one of our commonest trees, and is steeped in folklore. It’s easy to identify, and the timber is extraordinarily strong and versatile

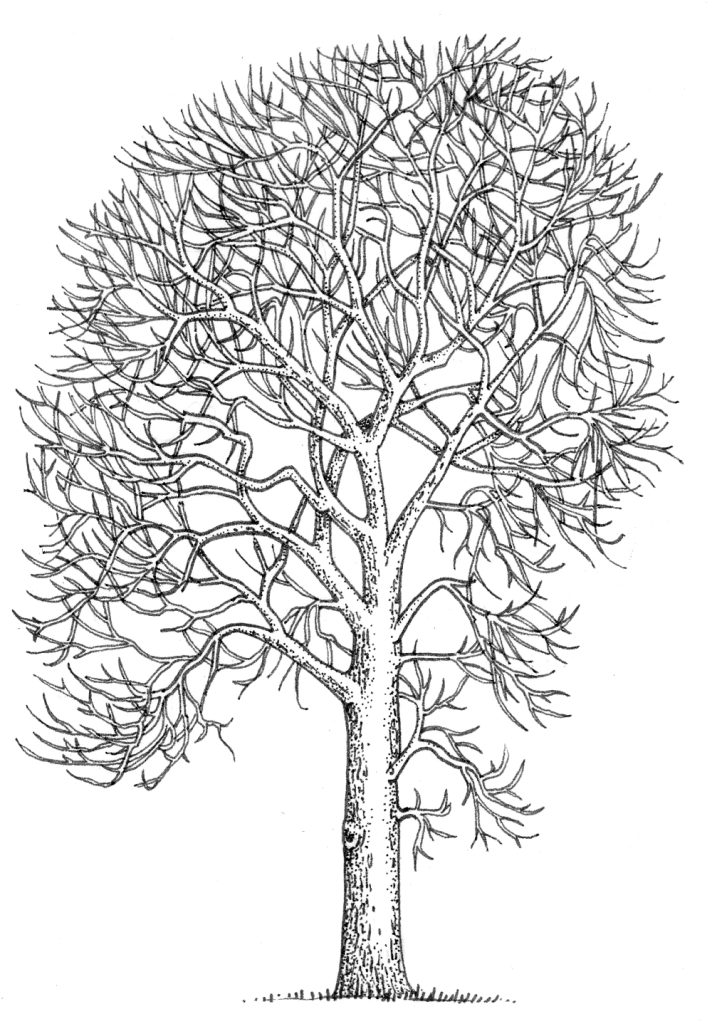

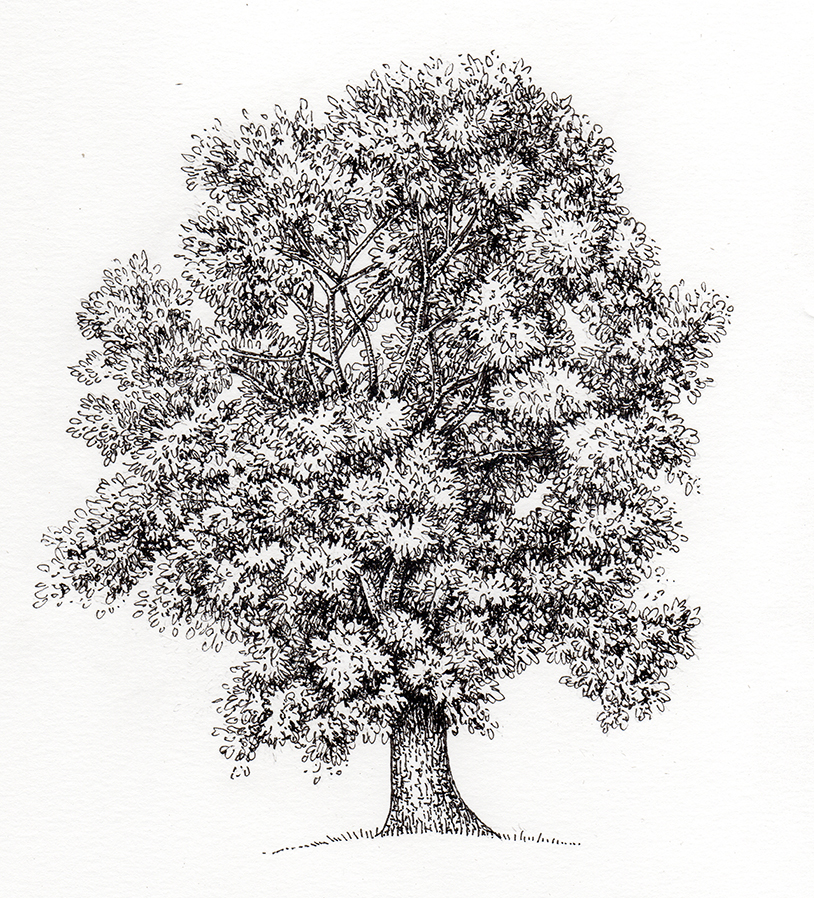

Identification: Tree shape

Ash trees have domes crowns, and grow up to 40m. In winter, they can be easily recognized as the ends of branches and twigs turn upwards.

They also have distinctive matt, black buds which would be hard to mistake for any other species. Ash grows in woodland, fields, and many other habitats. It’s one of the commonest British trees with over 150 million mature trees in the UK (The Conversation, 2019).

Identification: Leaves

Leaves of the ash are opposite. Each compound leaf comprises 9 to 13 short-stalked leaflets up to 7cm long, in opposite pairs. There is always one lone leaflet at the tip. This arrangement is called “Odd-pinnate”. (For more on compound vs simple leaves, have a look at my blog). Leaflets have long tips and small teeth on the margins (for more on leaf shape and margins check out my blog).

Identification: Flowers

Flowers of the ash emerge before the leaves (which are often amongst the last to unfurl in spring). Female and male flowers are carried on separate twigs, are without petals, and look like little purplish tufts.

Identification: Fruit

Like the Sycamore, the Ash has winged seeds, or samara (for more on samaras, which are basically just winged achenes, check out my blog. These are borne in clusters, with a single wing. Like Sycamore, ash seeds spin to the ground in a most satisfying manner.

Identification: Bark

Twigs are grey, and the tree bark is greyish-green. It becomes rough and fissured in older trees.

Similar Species

Several trees have similar odd-pinnate leaves, but should be easy to distinguish from the Ash. These include Elderberry Sambucus nigra, which is smaller, has highly scented frothy blossoms, pale bark, and lots of juicy purple berries in autumn. Walnut Juglans regia, tends to be a more substantial tree. It too has compound leaves, although these tend to be a paler green than the Ash. Walnut flowers are carried in green catkins, and the fruit is (of course) the edible walnut.

Elderberry Sambucus nigra

Mountain ash or Rowan Sorbus aucuparia is another similar species. However, it tends to be much smaller than the ash, has frothy white blossoms, and carries wonderful clusters of orange berries. The leaves have sharply serrated margins, and are blunter than ash. Leaflets are stalkless.

Rowan Sorbus aucuparia

History

In Scandinavia, Ash was worshipped as a sacred tree and Odin (the most powerful of the Norse gods) was said to have carved man from a piece of ash.

The Tree of the World, an enormous mythological Ash, appears in Nordic mythology. Also known as Yggrasil, its branches, trunk and roots entwined heaven, earth, and the underworld.

Ash was said to ward off witches, and a piece of ash carried in the pocket would ward them off, as well as keeping you safe from goblins and snakes. Farming tools made of iron and ash would protect the crops from witchcraft. Burning ash logs would chase the evil spirits from a room. Ash growing with Oak and Hawthorn signified the realms of the Fairy folk and otherworldly spirits.

Medicinally, passing an ill child through a cleft in an Ash would help healing. If you had a break or rupture, splitting a sapling and passing the patient through it would help. You bound up the tree (and, one assumes, the patient) and when the tree had healed, so too had the patient.

Uses

Ash keys are edible if you boil them a few times, then pickle them.

However, it’s the wood of ash that makes the tree so valuable. It’s almost white; and incredibly durable, flexible, and pliable.

Items made from ash include sledges, furniture, oars, tool handles, skis, hockey sticks, and even form part of the Morgan car. Rob Penn wrote a rather wonderful tree about the plethora of things that could be made from just one ash tree, “The Man Who Made Things out of Trees”. My other half makes gravel bikes using ash, and has plenty to say about it’s natural shock-absorbing capacities, and beauty. If it seems unlikely, take a look at his website, Twmpa Cycles.

Threats

As with all British trees, ash are cleared when hedgerows are grubbed up and habitat is lost to development.

This amazing tree is also under serious threat from Ash dieback. This fungal disease is projected to wipe out 95% of our ash trees, in a similar way to the eradication of Elm when Dutch Elm disease appeared. It’s estimated this loss could cost the UK up to£15 billion (The Conversation, May 2019).

The fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (previously known as Chalara fraxinea) affects the ash in a number of ways. It causes the leaves to wither, and the crown of the tree to thin. It also causes legions and cracks in the bark which allow the entry of other pathogens.

Young saplings will succumb quickly, but older trees hold out until another agent, such as Honey fungus, attacks it in its weakened form.

Ash dieback symptoms

There is no cure or treatment for Ash dieback, and it seems likely that our love for imported plants explains why the fungus is now ravaging the countryside.

For more on Ash dieback (also known as Chalara or Chalara dieback), check out the Forestry Commission website, and for information on the economic affects have a look at The Conversation’s article.

Conclusion

The ash is a beautiful tree, and common across the UK. Its wood is incredibly useful, and its folklore many-layered and interesting. The fact that such a part of the British countryside will soon become a rarity causes me a great deal of pain. All I can suggest is that while many of our ash trees remain, get out into nature and enjoy them.

Little owl Athene noctua with Ash leaves behind

References for this blog include the excellent “The Greenwood Trees” by Christina Hart-Davies, and the Reader’s Digest “The Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of Britain” (out of print but commonly available second-hand), and Collins Flower Guide by David Streeter.

Take a look at my other blogs on British trees, the Oak and the Sycamore.

Fantastic information about the Ash tree, and sad too.

Hi Irene

Thanks. Yeah, I know, it is rather sobering. But let’s enjoy seeing those fabulous trees while we can. Thanks for the comment. x