Botanical Illustration: Rosehips

This brief blog is due to my my awe on discovering that Rosehips are not, as I’d always assumed, true fruits.

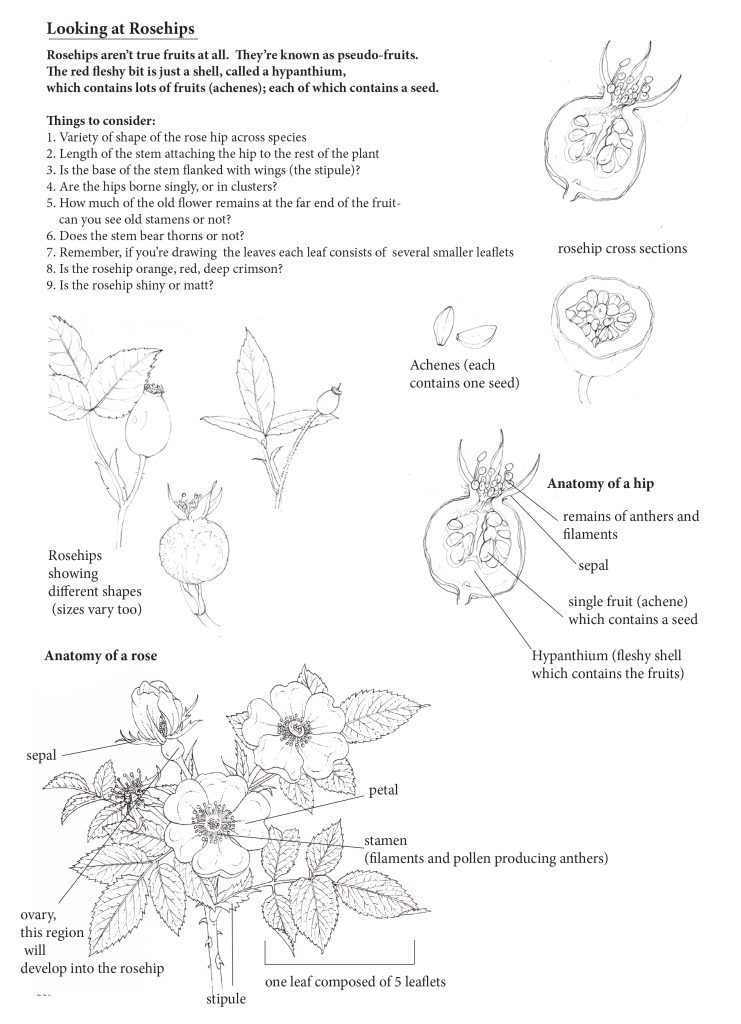

In autumn, roses produce hips. These come in a wide variety of shapes and colours, some showy and some much more discrete. The basic anatomy of all these varied rosehips is the same.

Rosehips are false fruit

The rosehip is a false fruit, also known as an accessory fruit. Other synonyms you may have come across include pseudo-fruit and pseudocarp. (Compound fruit is also used, and can describe both compound and multiple fruits.) An accessory fruit describes fruits from multiple ovaries which develop in a single fruit.

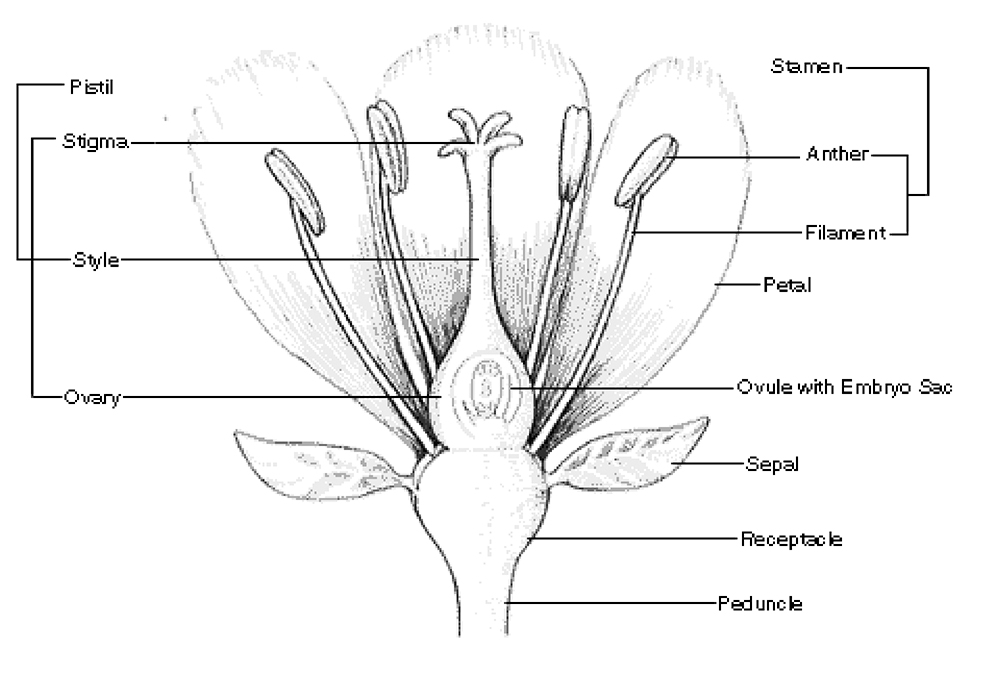

This means that the fruit (or hip) does indeed contain seeds. Importantly though, it contains a lot of other tissue too. The extra tissue does not come from the ovary alone, but from tissue near the carpel. (A carpel is the female reproductive structure of a flower. It consists of the ovary, pistil, style and stigma. These may occur singly, one carpel per pistil; or several carpels may be fused together into one big ovary. This unit is also known as a pistil.)

The diagram below shows a simplified and basic cross section of a flower.

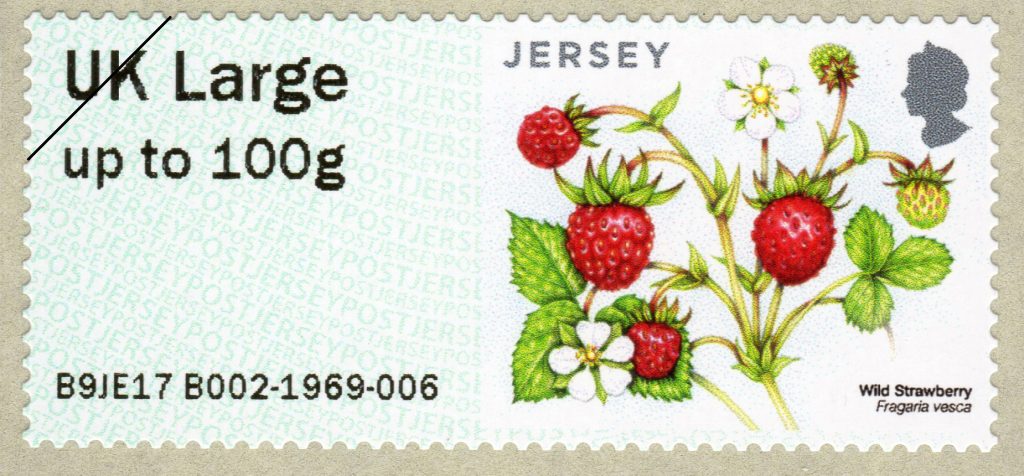

Roses are not the only plants with false fruit. Strawberries, pears, apples, and figs are all considered false fruits.

The extra tissue in a strawberry, pineapple and fig is formed from the receptacle (see the diagram above) which has become swollen as the seeds ripen. Strawberries carry their fruit on the external surface of the juicy receptacle tissue. Those little “pips” on a strawberry are actually individual fruits, bearing seed.

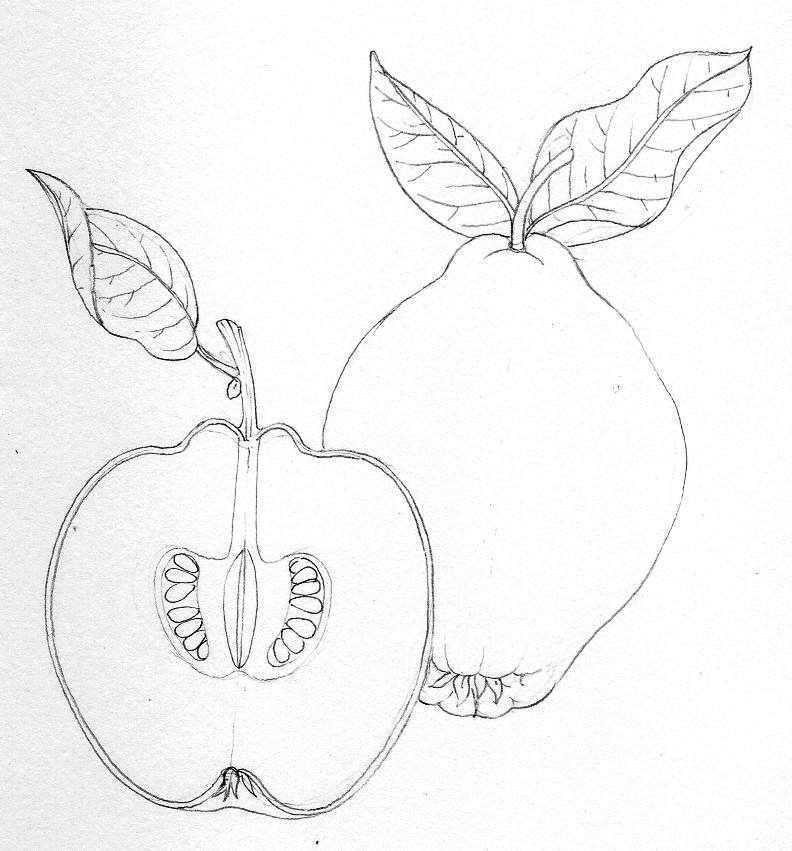

In the case of pomes like the rosehip, pear and apple the swollen tissue comes from the hypanthium.

A hypanthium is the area where the base of the calyx, corolla (petals), and stamens come together to form a tube. This is often cup-like, and can be referred to as a floral cup. The Rosaceae family (pears, roses, apples) all have these swollen hypanthium. In the case of the rose, the hypanthium is called a “hip”. For more on the Rosaceae, check out the Ohio Plants page.

You can easily see the ovary on a rose, it’s the slightly bulging green area below the petals and sepals. This is the hypanthium and, once ripe, becomes the hip.

Cutting a rosehip in half

When you slice a rosehip down the middle, you see lots of “seeds” and soft flesh. The outside of the hip is often scarlet or crimson, and the flesh attractive to animals which will eat it and thus disperse its seeds.

At the top of the hip, furthest from the stalk, you can see the remnants of the sepals, stamens and anthers. You can also see these on an apple, quince (below) or pear; they form the small basal star-like area.

The red fleshy part of a rosehip is actually just a shell, a hypanthium. Within this, though, lurk the seeds.

Inside the skin of the hypanthium is fleshy tissue, and areas crammed with seeds. Each of these seeds is, in fact, not a seed but a fruit, called an achene (for more on achenes check out my blog). Lots of single fruits or achenes. Inside each of these, lies a seed.

So to find the seed of a rose you need to travel through the red external skin, through the fleshy tissue, and through the achene wall of a single fruit. There, at the heart of things, sits your rose seed.

The rosehip is a perfectly designed seed-pod.

An overview of rosehips, and what to look for when you illustrate them

I created a handout explaining this anatomy, and also with a list of things to look at and consider when you do a botanical illustration of a rosehip. What shape is it? What colour? How long is its stem? Is it shiny? Is the hip solitary or borne in a cluster?

As I said, this is a brief (and slightly brutal) overview of the structure of the rosehip, nature’s perfectly designed seed container.

Beautiful drawing and fascinating details – I was looking for whether a ‘hip’ was a fruit or a seed, and this explains it so well, and so beautifully – many thanks

I am so glad to be of help! It did my head in too – lots of my blogs start out as me being totally non-plussed about something botanical. Thanks for letting me know it was useful.

Hello: I enjoyed your post on rosehips–especially the drawings. I was wondering if the “rose type” can be identified by the outer physical characteristics of the rosehip. For sentimental reasons, I have started a project to propagate rose plants from seeds from my grandparents rosebushes. I have noticed that some of the rosehips are sort of “pumpkin shaped” (and quite large–almost like golf ball but not as big) while others are “pear shaped” with pointy ends (kind of like a Herschy kiss chocolate), while others are more rounded like marbles. I suspect the size and shape differences due to different species. The rose plants are all kind of inter-tangled and the flowers are gone on most making it difficult to identify which rose family they come from. I have very fond memories of my childhood playing amongst the rose bushes–especially the scent of them when literally hundreds were in bloom. They were the big uneven roses that you hardly see anymore. The fact they are “disheveled” (not so perfect like a single stemmed rose) is what makes them that much more beautiful to me because they have character. Do you know of a reference which outlines the differences in rosehips from the rose family? Thank you in advance and sorry for such long explanation. I feel like the best gift I could give my siblings is a rose bush grown from a seed from my grandparents roses. Respectfully, Blue

Hi Blue,

Well, that comment led to some lively debate on Twitter when I asked the community of botanists for trheir recomendations! Many were annoyed that their trusted books on roses did not, in fact, have much on rosehips species by species. I can totally understand you wanting to explore this further, the idea of giving a rose to your brothers or sisters which come from the grandparents is lovely. Especially since those memories of your youth are so happy.

The booklist I’ve conjured up is pretty UK-centric, and some fo the titles are out of print. others (like Stace) may be a bit too intense and botanical (and the stace only has 1 page of rosehip illustrations in amongst 2200+ pages of other botany identifications!)

However, for what it’s worth, here’s the list for you:

Recommendations for Books on Roses and Rosehips

Roses of Great Britain and Ireland, Graham, G and Primavesi, A. BSBI Handbook No. 7

The Heritage of the Rose, Austin, D

The Peter Beales Classic Roses, Beales, P.

Roses, Philips, R. & Rix, M.

New Flora of the British Isles, Stace, C.

Thanks for taking the time to leave such a lovely comment, and good luck identifying those roses!

X

Thank you for the beautiful drawings and explanations! Perhaps you can help me with my quest: I enjoy eating rosehips in winter but, of course, I am annoyed that I have to be extra careful not to swallow the fuzzy hairs covering the seeds or get them to irritate my tongue. I was wondering whether, among so many cultivars with different flower colors and shapes, somebody has not selected one that lacks the irritating hairs within the hypanthium. For this, I tried to find out which is the embryonic origin of the hairs, for keywords to help my search (I’m not a native English speaker as you probably realized). It’s also possible that nobody has since there is no big economic incentive for this. I imagine that if we compare the rosehip with a curved sunflower inflorescence, that the hairs would correspond to hairs on the calyx or to simplified floral bracts. What do you think? Thank you!

Hi Tudor

Your English is impeccable, and I dont think I would have noticed unless you mentioned it. I totally understand the idea of getting rosehips with less fuzz on. I’m not sure if anyone has bred roses with less of this. I do know that generally people suggest the Dog Rose Rosa canina as the bes tone for hips though, but then you know that already. Scooting around online, the only term Ive been able to find for the fuzz is “hairs” or “seed hairs” which feels unsatisfactory to me. And yes, I think there’s every likelihood that the hairs have analogous structures in other seeds, although I can'[t think what they might be. I wish I could be more help! Interesting question though. And thatnks for the comment. x

You mention that pineapples have fleshy parts from the hypanthium but they are actually multiple fruits (berries) that have all coalesced from multiple flowers, and called multiple fruits. What you call false fruits are also called accessory fruits. Fruits from multiple ovaries in a single fruit are called accessory fruits like blackberries. Therefore a strawberry is an aggregate accessory fruit since the fleshy part is not part of the ovary and many ovaries from one flower that formed achenes are on one fruit. Sometimes the word compound fruit is used to encompass accessory and multiple fruits.

Hi Steve

THANKYOU so much for this. I write these blogs to try and understand the botany that I learn as I go along, and clarification like this is incredibly helpful. And the slight variations in the terminology and when its’ used can be deadly unless you truly know your stuff. So thankyou. I will edit and update the bloog now, thanks to your input. Much appreciated.

Hi Lizzie

Thanks so much for this info. I’m researching the gallica rose, ‘Violacea’ fir a botanical illustration course and am confused about information I’ve found which says it has a Superior ovary, “meaning it’s above the points where the sepals and petals attach to the flower”.

Surely it’s below the sepals and petals, as the rosehip itself (containing the ovules which eventually become the fruits) is below the sepals and petals?

Regards,

Susana

Hi Susana

I cant remember the details, Im afraid, but think its a “half inferior” or perygynous” ovary. Maybe this article will do a better job of explaining than I can? https://stbarbebaker.wordpress.com/2019/06/21/rose-reproduction/ Hope you untangle it soon, its always done my head in, ovaries.