Botanical Illustration: Exploring Adventitious Roots

In my last blog I mentioned that being a botanical illustrator sometimes involves a fair amount of research, in this case examining different types of root. Natural history illustration and botany go hand in hand. In researching roots I’ve realised that the more you learn, the more you find you need to learn. This blog is about adventitious roots.

Growth pattern of Adventitous roots

Adventitious roots, roots which don’t grow from the base of a plant’s stem but can grow from other parts of the stem or from the leaves, are useful for plants both for nutrient storage and for structural support. They can also have specific other functions, as we shall see.

These roots are primarily useful as they allow for vegetative propagation, new plants being able to grow from rooting nodes along the stem (as with this aquatic plant the Fringed water lily Nymphoides peltata).

Fringed water lily Nymphoides peltata with adventitious roots

Adventitious Storage Roots

Adventitious storage roots are thick and fleshy. Plants use them to live through tough growing conditions (such as winter) without having to rely on seeds alone for survival There are a few types of these roots, depending on what part of the plant they develop from.

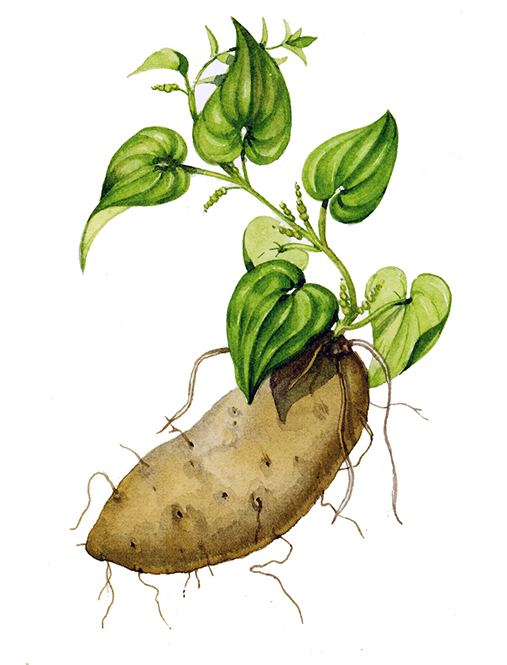

Tuberous adventitious roots have no set shape and have no eyes (unlike the potato which is a tuber, not a tuberous root!) or bud scales. They develop from a single node on the stem; each node produces one tuberous root eg. yam or sweet potato.

The Yam has a swollen tuberous root

Fasciculate adventitious roots develop from the base of the plant, in a cluster.

Dahlias have fasciculated roots

Moniliform roots

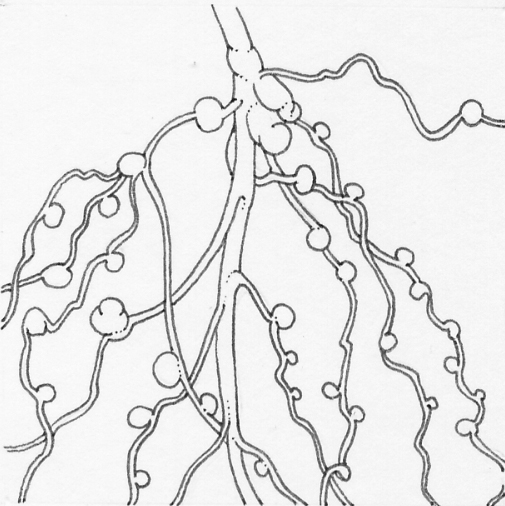

Moniliform adventitious roots are swollen at frequent intervals. This gives them a form rather like a string of beads. Portulace or moss roses have these moniliform roots, as does Basella, some grapes, and wood sorrel Oxalis acetosella.

Wood sorrel has moniliform roots, although these are not clear in this specimen I illustrated.

When a root suddenly swells at its tip, it’s called a nodulose root. An example is the Mango ginger Curcuda amader.

Annulated roots are marked with ring like segments, or rings. They look as if they’re discs, stacked on top of each other. These may be different colours, swellings, or a ring of hairs. Examples of these are the Ipecac Physcotria.

Adventitious Supporting Roots

Various forms of support can be provided by adventitious roots.

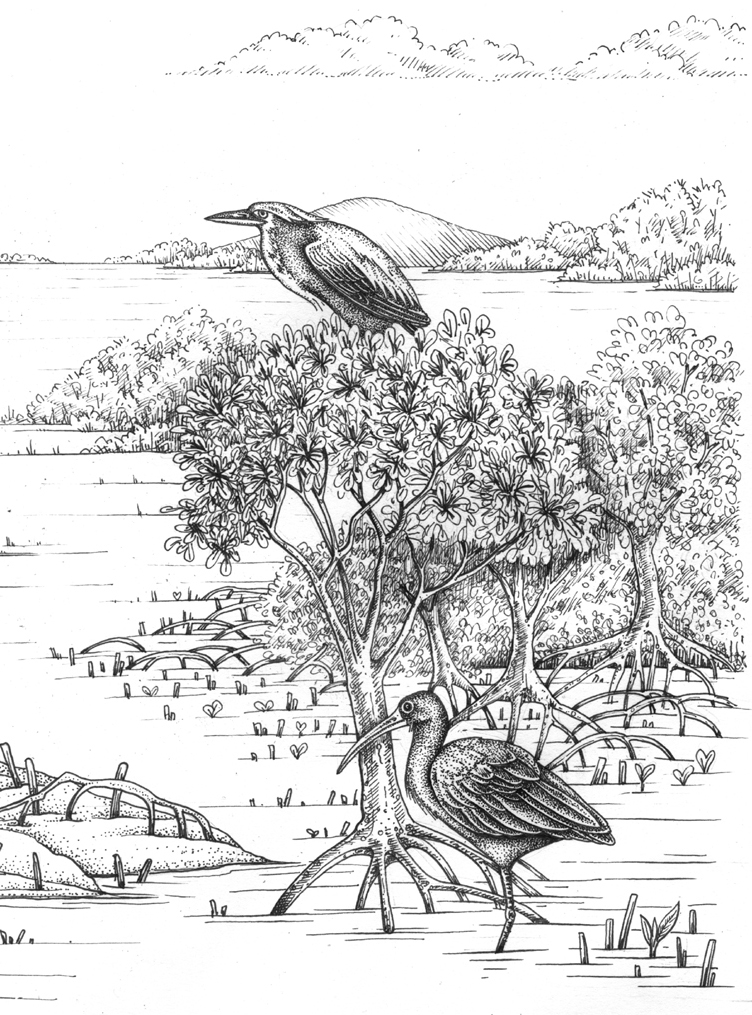

Prop roots (eg. the Banyan tree) grow out of the branch of a plant, and into the ground below, helping to stabilize and secure it. These are often found on plants growing in places where the substrate is thin, and large plants and trees have to anchor themselves without a network of widely branching, deep roots.

Mangrove tree with prop roots helping to secure it in the changing tidal mud.

Stilt roots grow from nodes near the base of a stem and help secure the plant into the ground from just above the substrate. Maize and sugarcane have these.

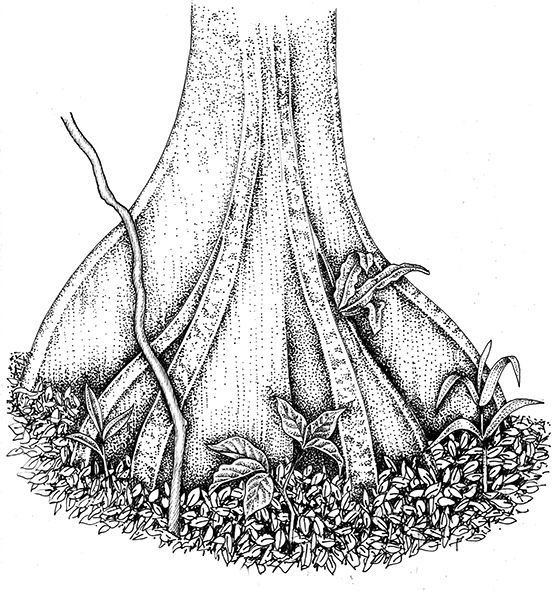

Buttress roots are a mechanical support at the base of a tree, sometimes referred to as “woody fins”. Yet again, they help anchor a large tree to a thin substrate such as the jungle floor.

Buttress root

Some climbing plants will develop roots from nodes on their stems to help them climb up other plants (eg. Betel) whereas others have developed clinging roots that help them live as epiphytes (eg. orchids).

Other uses of Adventitious Roots

Some plants have highly specialised adventitious roots. The roots of some epiphytic plants are covered with an absorbent layer of velamen which they use to absorb moisture from the air, (eg. Vanilla)

Assimilatory roots (eg. Tinospora or Guduchi) are able to become green and photosynthesise, thus providing extra nutrients for the plant.

Mycorrhizal adventitious roots are common in many plants and have a partnership with certain fungus species; both fungus and plant require each other (eg. Pinus speces). This relationship increases water absorption and allows the plant to access certain minerals.

The parasitic Dodder plants (Cuscutaceae) have adapted their roots to become roots which suck nutrients from their host plants (these sucking roots are known as hausteria).

Dodder parasitic plant species with sucking advantitious roots (Copyright HarperCollins 2006)

Some aquatic plants use adventitious floating roots full of water to help them stay afloat (eg. Jussiaea)

In some sources, Contractile roots are considered another specific use of adventitious roots. These can be found in the underground stems of some garlic and onion species. They’re at the tips of some slightly thicker roots. These tips contract and thus help allow the plant to be firmly attached in the soil.

Adventitious roots and nitrogen fixing

The final specific use of adventitious roots is nodulated roots. Areas of certain plants, such as pulses and legumes, are given over to numerous tiny nodes. In these, a symbiotic relationship with bacteria occurs. This fixes nitrogen from the soil into the plant. These bacteria can convert nitrogen from the atmosphere into ammonia. This occurs inside the airless nodules. One last step converts this fixed nitrogen into amino acids, useful proteins for the plant.

Nodules on leguminacious roots

White clover is one of many species with nodulated roots.

White clover Trifolium repens

I am indebted to Root Engineering: Basic and Applied Concepts edited by Asunción Morte, Ajit Varma which has helped me with research for this blog, as has The New Plant Glossary by Henry Beentje and the online Biology Tutor pages on root adaptation

I hope this brief look into the world of adventitious root variety, form, and function has been as amazing to you as it has been to me. Evolution is indeed a marvellous thing!