Natural History Illustration: Insect anatomy

Insects are my favourite creatures. I love illustrating them in my natural science commissions. Here’s a brief overview of the parts of any insect which should help anyone doing entomological illustration.

Insect overview

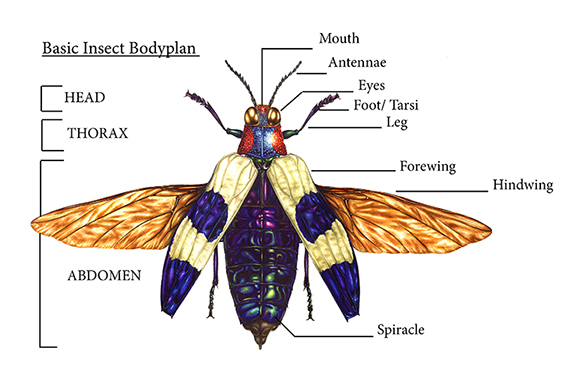

Insects are invertebrates; they sport an external skeleton rather than internal bones. Their limbs are jointed, they’re cold-blooded, have six legs and (mostly) two pairs of wings. Their body is split into three sections; the head, thorax and abdomen.

Any insect can be split into three parts. There’s a head (box-shaped and containing the insect’s sense organs and mouth). The there’s a thorax (the middle, where the wings and legs attach). Finally, there’s an abdomen (the rear section where breathing and digestion/ excretion/ reproduction occur).

The Head

Insects sense the world around them with eyes. These can be simple or made of many lenses (compound). Some insect eyes merely detect light and dark; others can see all the colours we see, plus ultraviolet light. A top insect predator, such as a dragonfly, has thousands of lenses building up its compound eye and their eyesight is pretty acute. (For more on dragonflies, check out my blog.)

Antennae are attached to an insects head and let it smell, taste, and touch the world around it. They pick up vibrations too. Like most insect features they vary wildly from animal to animal. Consider the incredibly long antennae of a blind cave cricket next to the furry ones of a moth. The first sort senses the area around the insect, the second picks up pheromones and helps locate a mate.

Insect’s mouths allow the insect to feed. However, some insects don’t eat as adults (the mayfly for example), and have no mouths at all. With food stuff as varied as leaf-litter to other insects, seeds to wood and meat, insect mouths have evolved into a regular toolbox for feeding. Crushing, slicing, sucking through straws, chewing through trees – insects have evolved them all. Mouths also can also get rid of waste products, deliver bites, and produce silk and venom.

The Thorax

This is the power-house of the insect. Wings and legs are attached to this box-like structure; within it lie the muscles to drive locomotion.

Legs are segmented and are are used for walking, jumping, swimming, and digging.

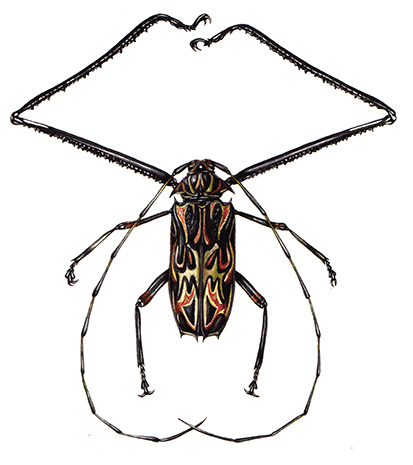

This Harlequin beetle, Acrocinus longimanus, has extraordinary legs which it uses to attract females, and to get across tree branches in its South American rainforest home.

Feet are good for gripping and cleaning; they may have sensitive hairs which help the insect feel danger from behind.

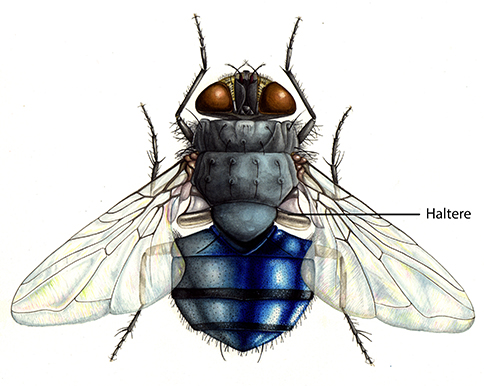

Insects have two pairs of wings; forewings (at the front) and hindwings (behind). These are used for flight and display. Some insects have lost their wings entirely (like the ants) whilst others have adapted them enormously. Beetles have evolved their forewings into tough coverings, or elytra, which enable them to exploit all sorts of habitats. This doesn’t compromise their ability to fly. Flies have adapted their hindwings into tiny lolly-pop like structures called halteres. Halteres work like gyroscopes, allowing complete control over rotation and direction when flying.

The blue-bottle fly, Calliphora vomitoria, showing halteres. These are easiest to see on a crane fly (daddy long-legs).

The Abdomen

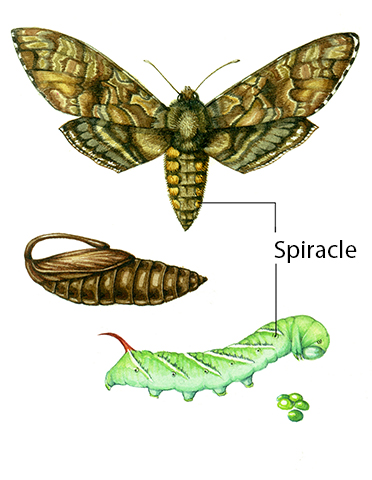

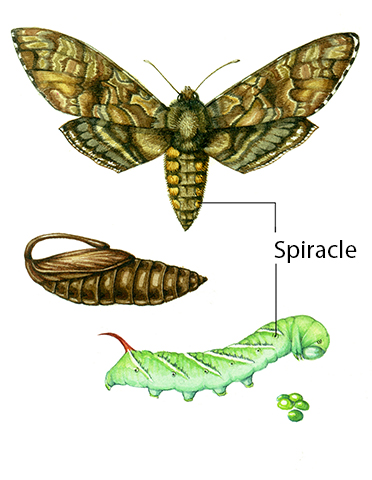

Insect abdomens are the site of digestion, excretion, circulation, and respiration. Their hearts are here, and although different to ours they do the same job. They pump blood around the insect’s body. Insects breathe through their abdomens too, through small holes called spiracles which connect to internal tubes (trachea). These connect to smaller tubes (tracheoles) which terminate in water filled spaces of 1 micrometer or less. This is where gas exchange occurs.

Caterpillars are good subjects if you want to see spiracles; they often appear as dark spots along the animal’s side. This one’s a tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta).

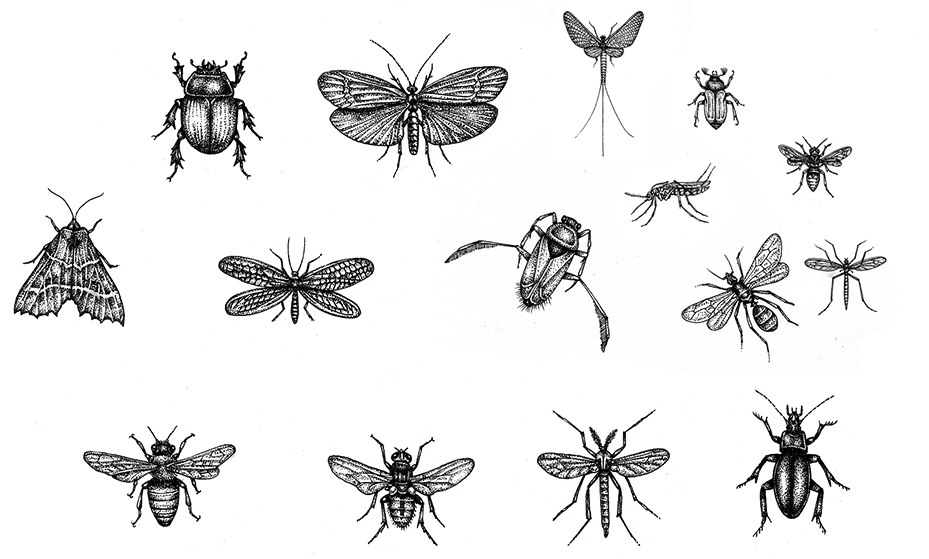

The most wonderful thing about insects is their adaptability, they’ve taken this basic body plan and run with it in thousands of different evolutionary directions. To see if you’ve got the basics sorted, try to identify all the key insect features on the insect illustrations below.

There’s so much to say about insects, and how magnificent they are, that it’ll doubtless be a topic I return to. For more on insects, and for links to help learn more, have a look at the Amateur entomologists society page.

Dear Lizzie,

A entomologist friend has lent me a box of insect treasures to illustrate.It is not a commission. He is just someone who knows how much I enjoy painting botanical watercolour illustrations and looking at bugs. I am excited but daunted by the task. I found your Insect Anatomy pages on the web just now and am so greatful to you for taking the time to create such a helpful post.

Now I’m really looking forward to discovering what I can about these beautiful creatures and attempting the illustrations.

Thank you very much.

Jan Tabler

Hi Jan

What a treat! You’ll have an absolutely wonderful time, I’m sure. SO much easier to have the actual specimens instead of photos to work from. Im glad my crash course in insect basics was useful. ENjoy it!

Yours Lizzie